Indigenous Australians are respectfully advised that the following includes the names and images of some people who are now deceased.

The Reserve Bank of Australia has announced that Queen Elizabeth II’s portrait on Australia’s $5 banknote will not be replaced by one of Charles III (as is happening in the United Kingdom). It will instead show a design that “honours the culture and history of the First Australians”.

While some will complain this is a break from the tradition of the reigning monarch’s head being on the lowest-denomination banknote, that has only been the case in Australia since 1966, when decimal currency was introduced.

Before that, navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders appeared on the lowest (ten shilling) note. The queen was on the pound note (equal to 20 shillings).

The Reserve Bank of Australia consulted the federal government, which supports the change, but the decision is its own.

An opinion poll last year indicated just 34% of Australians wanted to see King Charles replace his mother on the $5 note, with 43% preferring another person, such as a famous Australian, and 23% undecided.

Putting King Charles III on British currency bucks a global trend to honor diverse national heroes on coins and bills

What will the new design show?

Will the design honour an Indigenous individual, or a group, or First Nations people more generally? It will likely be several years before we know.

Banknote design is complex, and the central bank will need to consult widely and deeply with Indigenous Australians to avoid the cultural insensitivities that have marred previous efforts to depict Indigenous motifs or individuals.

What we do know is the note’s other side will show an image of Parliament House, as it does now. The current design includes the Forecourt Mosaic, which is based on Michael Nelson Jagamara’s work Possum and Wallaby Dreaming.

RBA, CC BY

A return to tradition

While breaking with one “tradition”, an Indigenous motif on the lowest-denomination banknote restores another.

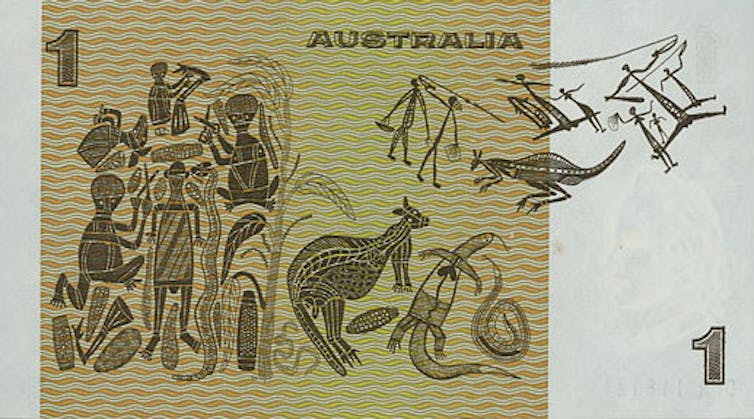

When decimal currency was introduced in 1966, the lowest-denomination banknote was the $1 note. One side featured a youthful Queen Elizabeth and the Australian coat of arms. The other showed an Indigenous design, based on bark painting by artist David Malangi Daymirringu, a Yolngu man from what is now northeastern Arnhem Land, and others.

RBA

The Reserve Bank’s governor at the time was HC “Nugget” Coombs, a strong advocate for Indigenous Australians. But to his later embarrassment, it turned out no one at the bank thought to ask permission to copy the artworks used in the design – nor offer payment.

Only after the banknote was issued did an Adelaide newspaper report on the treatment of Malangi, who came to be known as “Dollar Dave”.

Coombs subsequently sought to make amends. Malangi was paid $1,000 (the same given to those whose art was used on other banknotes), a fishing kit and a special medallion Coombs commissioned.

The $1 note was phased out in 1984 (replaced by the $1 coin, showing a mob of kangaroos, in keeping with animal motifs on Australian coins).

‘Dollar Dave’ and the Reserve Bank: a tale of art, theft and human rights

David Unaipon and the $50 note

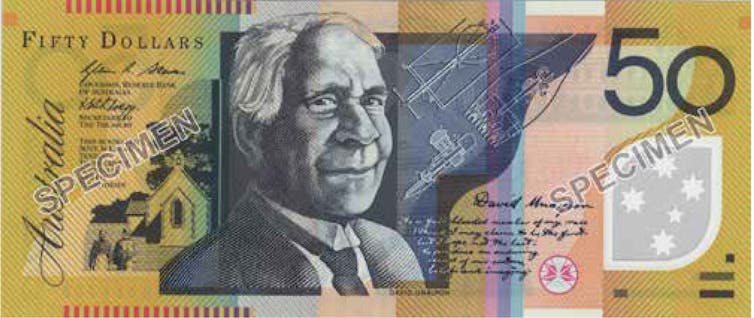

The first Australian banknote to honour an Indigenous individual was the $50 note in 1996, with the change from paper to polymer notes.

Portraits of scientists Howard Walter Florey and Sir Ian Clunies Ross were replaced by Australia’s first female parliamentarian, Edith Cowan, and David Unaipon, a Ngarrindjeri man from what is now southeastern South Australia.

RBA, CC BY

Unaipon (born in 1872) was a preacher, inventor and author. He was an expert in ballistics and believed the aerodynamics of the boomerang could be applied to aircraft.

His book, Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals, was the first by an Indigenous author to be published in Australia – though without credit (W. Ramsay Smith, SA’s chief medical officer, was listed as the author). The book was finally republished with Unaipon’s name on the cover in 2006.

Gwoya Jungarai and the $2 coin

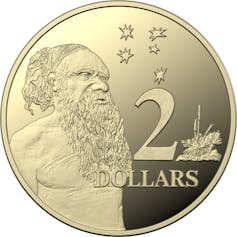

Royal Australian Mint, CC BY

The first Australian coin to feature an Indigenous Australian was the $2 coin in 1988, showing Gwoya Jungarai (sometimes spelled Tjungurrayi).

Known as “One Pound Jimmy”, he was a survivor of the Coniston Massacre in the Northern Territory in 1928, when police killed at least 31 Warlpiri men, women and children.

This was a time when chief protectors were appointed to “watch over the interests” of First Nations people, and to “smooth the dying pillow” for a race of people who had been brought to the edge of extinction.

The image of Gwoya Jungarai came from a photo of him in 1935. This was used on a postage stamp in 1950, making him the first living Australian to be so featured.

Elder, lawman, survivor: stamp research is the latest chapter in Gwoja Tjungurrayi’s remarkable life in pictures

What do other Commonwealth countries do?

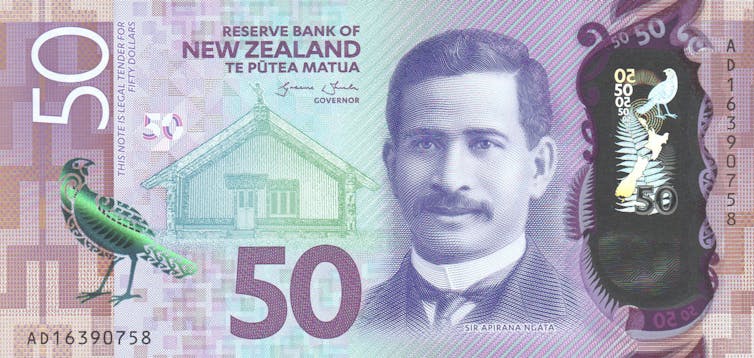

New Zealand has the Indigenous name of the country (Aotearoa) and its Reserve Bank (Te Pūtea Matua) on its notes. This is feasible as there is one dominant Indigenous language, whereas in Australia there are hundreds.

One note (the $50) honours a Māori individual Apirana Ngata, the first Māori to graduate from a local university and a parliamentarian for 38 years.

RBNZ, CC BY

Canada’s $50 note includes the Inuit word for “Arctic”.

The Reserve Bank of Australia is a founding member of the international Central Bank Network for Indigenous Inclusion, along with its peers in Canada and New Zealand. So there may be international discussion of the issues involved.

But the key to ensuring the design fulfils its potential to bring the country together and heal old wounds will be to consult with those whose culture and history the design is meant to honour.