In the end there was no red wave. And there was no blue wave.

There was an independent wave.

Pollsters and pundits were counting on independent voters in the 2022 midterm elections to swing to the Republicans as they did in 2014 when Barack Obama was president. That’s when independent turnout in the midterms added up to 29% of all voters, and the GOP won an additional 13 seats in Congress.

Expectations for the 2022 midterm elections also were based on a similar pattern in the 2018 midterms, when Donald Trump was president. Independents then represented 30% of the voters, and they broke for Democrats 54% to 42%.

Almost the mirror image. But mirrors don’t always reflect reality.

Ongoing surveys by the Gallup organization show that self-identified independents have averaged 42% of the U.S. public over the past year. Their influence was felt in the 2022 midterms.

Nationally, these nonaligned voters were 31% of voters in the 2022 midterm. Despite the fact that the sitting president was a Democrat, they broke for Democrats by 2 percentage points, according to Edison Research Survey. They voted for Democrats by far bigger margins in key states with competitive Senate races – by 20 percentage points in Pennsylvania, 11 percentage points in Georgia and 16 percentage points in Arizona, where independents were fully 40% of those who voted.

Independent voters in the 2022 midterms made a decisive difference in close elections.

This came as a surprise to many pollsters and pundits who had predicted that independents would break for the GOP. They chalked up the pro-Democratic leanings of these unaligned voters to independents’ distrust of Republicans’ eclipsing their anxiety and distrust about inflation and the economy.

Maybe so. But as someone who studies independent voters in the U.S., I believe pollsters got it wrong because so little is known about the voting patterns of independent voters.

The continuing flight of millions of voters from the Republican and Democratic parties is reshaping the nation’s political landscape in ways no one can control or even predict. It threatens the very basis on which campaigns and elections have been analyzed.

This is a challenge to how America has for generations thought about politics: that it’s a two-party game and people vote for the party they’re loyal to. With growing numbers of independent voters, that’s changing.

iStock / Getty Images Plus

Independent voters or shadow partisans?

As outlined in our recently released book, “The Independent Voter,” my co-authors Jacqueline Salit and Omar Ali and I outline how political scientists and the media have been extremely skeptical and dismissive of independent voters. They often conclude that independents are uninformed, uninvolved “leaners” or “shadow partisans” who are likely voters for Democrats or Republicans but just don’t want to say so out loud.

We believe that conclusion is based on the two-party bias that is baked into the U.S. political system. That bias has misshaped the research and analytical tools used to understand this community of Americans.

A fundamental misunderstanding

Beginning in 1952, when individuals identified themselves to pollsters and researchers as independent voters, they were then asked a follow-up question: Did they prefer one party over the other?

Since most independents indicated a lean toward one of the two major political parties’ candidates, political scientists have labeled them as “leaners,” independents who are likely to vote for one party or another. Political scientists also created a category called the “pure independent,” which was used to describe the fewer than 10% of people who truly refused to say whether they leaned one way or another.

Based on our research, we believe that this conclusion is a fundamental misunderstanding of independent voters and their voting patterns. This misunderstanding has led to mistaken assumptions about this growing population of U.S. citizens who have chosen to distance themselves from the two major parties.

Currently, 42% of Americans identify as independents. This is the highest percentage of independents in more than 75 years of public opinion polling. They rarely numbered more than 20% of voters from 1940 to 1960.

Independents move around

The choice to identify as an independent is a meaningful one, especially so in these politically hyperpolarized times, when many Americans do not feel or no longer feel at home in either party.

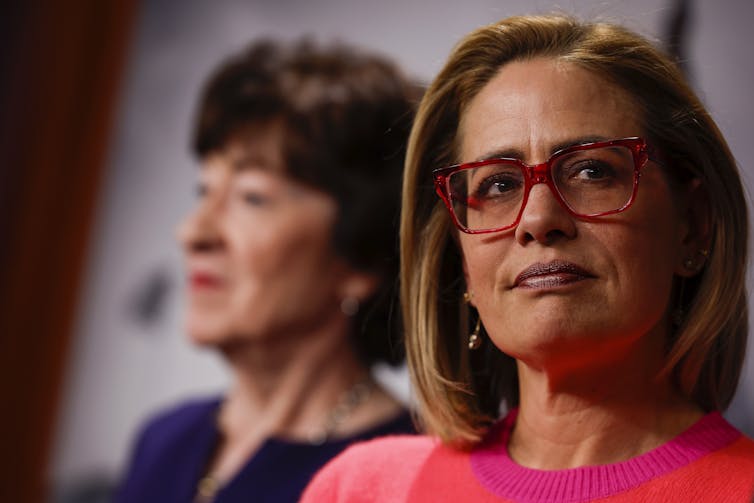

This is the reason Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema gave for her December 2022 decision to change her party affiliation from Democrat to independent. Sinema said she believes that “[e]veryday Americans are increasingly left behind by national parties’ rigid partisanship, which has hardened in recent years. Pressures in both parties pull leaders to the edges, allowing the loudest, most extreme voices to determine their respective parties’ priorities.”

Surprisingly, little research has been done to investigate the meaning and culture of political independence, including very basic research into independent voting patterns over time.

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

In our recently published research in the journal Politics & Policy, my colleague Dan Hunting and I analyzed American National Election Studies data on political identification and voting choices from 1972 to 2020.

We observed significant volatility in loyalty to party among independent voters over more than one election. We found that independent voters were not reliably tied in their votes to one party or the other. From one election to another, they voted for Democrats, then Republicans and back again.

We also found evidence that a sizable number of independents move in and out of independent status from one election to another and in many cases actually register as members of one party or another, sometimes differently from one election to the next.

We suspect this a function of the political candidates running at any given time. It also reflects the fact that many states don’t allow independents to vote in primaries, or otherwise restrict their participation in primaries by requiring them to choose a major party ballot in order to vote. Currently, independents are barred or restricted from primary voting in half the states. And a sizable number of independents are similarly locked out of presidential primaries and caucus voting.

They’re unpredictable

Why does this matter?

We believe that classifying independent leaners as Republicans or Democrats mischaracterizes the partisanship of Americans and overestimates the rate of party voting. Most studies that find leaners are partisans simply do not account for a sizable number of independents who move in and out of independent status. Those studies also do not account for the voting patterns of independents over time.

In our research, we found that independents who vote as Democrats or Republicans in one election are often less likely to vote that way in the next election.

Which party’s candidates or initiatives they vote for often depends on specific candidates or issues on the ballot and on the political circumstances of any given election cycle.

Consequently, independents may have voted against the party in power in midterm elections for a decade. But when circumstances and options change, their voting patterns change, too.

This may well turn out to be a defining feature of being an independent: that individual candidates, issues and the broader social environment – not party loyalty – drive their choices.

Unpredictability characterizes independent voters in modern times. This is what gives them their power – and it is why a deeper understanding of this group is urgently needed.