Cochlear implants are among the most successful neural prostheses on the market. These artificial ears have allowed nearly 1 million people globally with severe to profound hearing loss to either regain access to the sounds around them or experience the sense of hearing for the first time.

However, the effectiveness of cochlear implants varies greatly across users because of a range of factors, such as hearing loss duration and age at implantation. Children who receive implants at a younger age may may be able to acquire auditory skills similar to their peers with natural hearing.

I am a researcher studying pitch perception with cochlear implants. Understanding the mechanics of this technology and its limitations can help lead to potential new developments and improvements in the future.

How does a cochlear implant work?

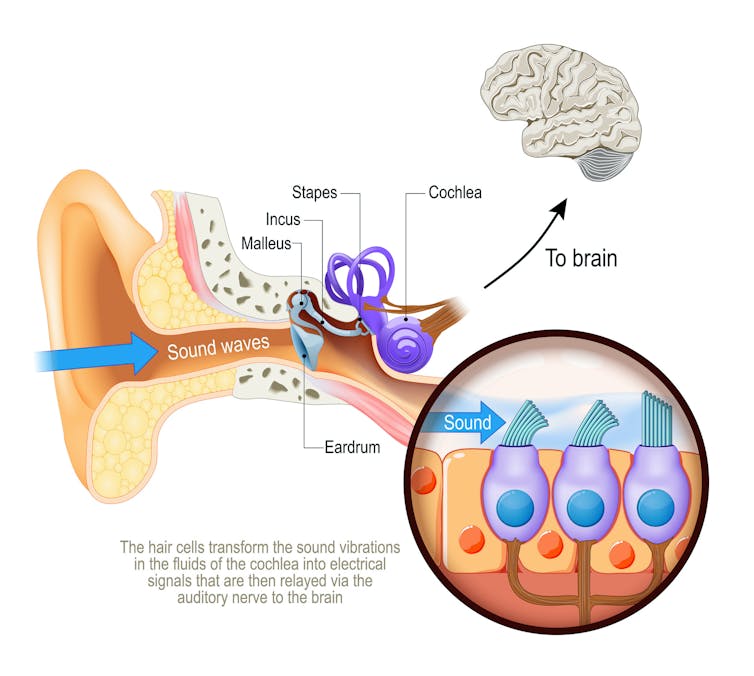

In fully-functional hearing, sound waves enter the ear canal and are converted into neural impulses as they move through hairlike sensory cells in the cochlea, or inner ear. These neural signals then travel through the auditory nerve behind the cochlea to the central auditory areas of the brain, resulting in a perception of sound.

People with severe to profound hearing loss often have damaged or missing sensory cells and are unable to convert sound waves into electrical signals. Cochlear implants bypass these hairlike cells by directly stimulating the auditory nerve with electrical pulses.

ttsz/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Cochlear implants consist of an external part wrapped behind the ear and an internal part implanted under the skin.

The external unit, which includes a microphone, signal processor and transmitter, picks up and processes sound waves from the environment. It divides sounds into different frequency bands, which are like different channels on a radio, with each band representing a specific range of frequencies within an overall spectrum of sound. It also extracts information about amplitude, or loudness, from each frequency band.

It then transmits that information to the receiver in the internal unit implanted in the cochlea. The electrodes of the internal unit directly stimulate the auditory nerve with electrical pulses based on amplitude information. Electrodes at the base of the cochlea transmit electrical signals containing high-frequency auditory information while electrodes at the top transmit electrical signals containing low-frequency information to the brain, mimicking the frequency analysis in a fully-functioning ear.

Where cochlear implants fall short

While people with cochlear implants are able to detect sounds and perceive speech in quiet environments reasonably well, they often have great difficulty understanding speech in noisy environments, enjoying music and localizing sounds, that is, figuring out which direction a sound is coming from.

Cochlear implants are fundamentally limited by their poor ability to tell the difference between sound frequencies and transmit rapid variations in sound amplitude over time. For example, current cochlear implant systems use only 12 to 22 electrodes to stimulate surviving auditory nerve fibers, whereas natural hearing has 30,000 auditory nerve fibers to encode detailed information about incoming sounds. Furthermore, electrode stimulation inside the cochlea excites a large group of auditory nerve fibers without much precision.

These factors result in poor frequency resolution. Picture it like painting with a thick brush that can show only an overall shape without the fine details, or only blurry details.

Why cochlear implants work better for some

It remains difficult to accurately predict the performance of cochlear implants for each user.

There are a variety of factors that can affect the number of healthy auditory nerve fibers available to transmit acoustic information to the brain. Cochlear implant users with better survival of their auditory nerve fibers may have improved frequency and timing representations of sounds represented by electrical stimulation, which can lead to better speech and pitch perception.

Neural health is not the only factor that contributes to variability in cochlear implant effectiveness. One 2012 study of 2,251 cochlear implant users found that speech recognition varied greatly, and only 22% of the difference could be explained by clinical factors like length of experience with the implant and cause of hearing loss. Furthermore, it is challenging to directly assess the effects of neural survival on the performance of cochlear implants. This suggests that other factors also play a role in determining the success of speech recognition with cochlear implants.

For instance, research has found that cognitive skills like working memory can influence the extent to which a person can understand speech after implantation. Cochlear implants increase cognitive load, or the amount of mental effort required to perform a task, as the sound quality users hear is often lower than that of natural hearing. Aging may also negatively affect cognitive processing skills, including attention deficits and slower processing speed on listening tasks.

Furthermore, most of the implant’s electrode arrays don’t reach the top of the cochlea where low-frequency information is conveyed in natural hearing. This leads to mismatches between the frequencies conveyed by the implant and those of natural hearing, resulting in reduced sound quality.

Elizabeth Hoffmann/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Improving cochlear implants

Scientists are investigating a number of potential ways to improve the effectiveness of cochlear implants.

Hearing sound through electrical stimulation is a new experience for those used to hearing without an implant. Auditory training exercises can help familiarize users with this new form of hearing and may even enhance overall speech and music perception. However, even with training, conventional cochlear implants may not fully replicate the rich experience of natural hearing.

Researchers are studying the potential use of light beams instead of electrical pulses to obtain better frequency resolution. This is done by genetically modifying the auditory nerve fibers to make them sensitive to light. Because light beams are able to more selectively stimulate auditory neurons compared to electrical pulses, this tactic may result in more precise frequency information. The research team behind this approach aims to start clinical trails in 2026.

Another approach involves inserting electrodes directly into auditory nerve fibers instead of the cochlea. By increasing the number of available electrodes, this strategy may enhance the sound frequency and timing information of the implant, and improve speech understanding in noisy environments and music perception.

Lastly, another development uses magnetic stimulation to transmit acoustic information via small, implantable microcoils. This approach allows for finer stimulation patterns than the widespread electrical activation of traditional electrodes, potentially leading to more precise sounds representation.

Research on new technologies may provide solutions to further improve the hearing experience for those struggling with hearing loss.