In the lead-in to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, it is revealing to look back on the media coverage of women’s international soccer to measure how far attitudes have shifted for today’s Matildas.

Media coverage is important. It builds personalities, creates public knowledge, sustains interest, draws crowds, attracts sponsors and generates participation.

Since the 1930s, sports journalists have written articles about sportswomen for major newspapers. These articles record years of player dedication and hard work.

But not all media coverage has treated sportswomen with respect.

The first Australia/New Zealand match

Women’s international soccer surged in the mid-to-late 1970s. The first recognised international soccer game between Australian and New Zealand women was played in October 1979 on a Saturday afternoon in southern Sydney.

The day before the match, a small advertisement appeared on page 68 in the Sydney Sun. Accompanying it, the newspaper profiled only the male referee.

The crowd that attended the match numbered about 200. There were no sponsor banners, corporate boxes or grandstands. There was little media. No dignitaries addressed the crowd. No one remembers if national anthems were played.

Football Australia

The women filed out of the change room in ill-fitting, borrowed men’s uniforms. There was no official team photo. The controlling body, the Australian Women’s Soccer Association, sold a small program for 20c.

When football stalwart Heather Reid and I interviewed many of the players from that game 40 years later, their memories were hazy and uncertain. Even Heather, who had driven from Canberra to watch the match, could not recall specific details.

To fill the gaps of memory we sought out players’ scrapbooks – but we were uncertain what we would find.

Long-range goals: can the FIFA World Cup help level the playing field for all women footballers?

Collecting the clippings

The leading men’s soccer player and Australian captain in the 1970s, Johnny Warren, amassed numerous scrapbooks filled with clippings, photographs, programs and fan letters.

Warren’s scrapbooks weigh more than 150 kilograms – more than twice his playing body weight.

We believed there had been little press coverage of women playing soccer in this era, and thought: how could women fill even one scrapbook?

What we found surprised us. It was rare for women not to have kept a scrapbook. Australian soccer captain Julie Dolan had a folder of cuttings related to her career, as did many of the Australian and New Zealand team members from 1979.

Author provided

Here was not a dearth but a wealth of newspaper coverage.

But there was a sting in the tail. While the quantity existed, as I looked closely I found it confronting and unsettling. These scrapbooks contained newspaper clippings that belittled, trivialised and sexualised these women and the sport they played.

Women sportswriters were critical to the growth of cricket in the 1930s. How have we gone backwards?

The sexist, underestimating press

Author provided

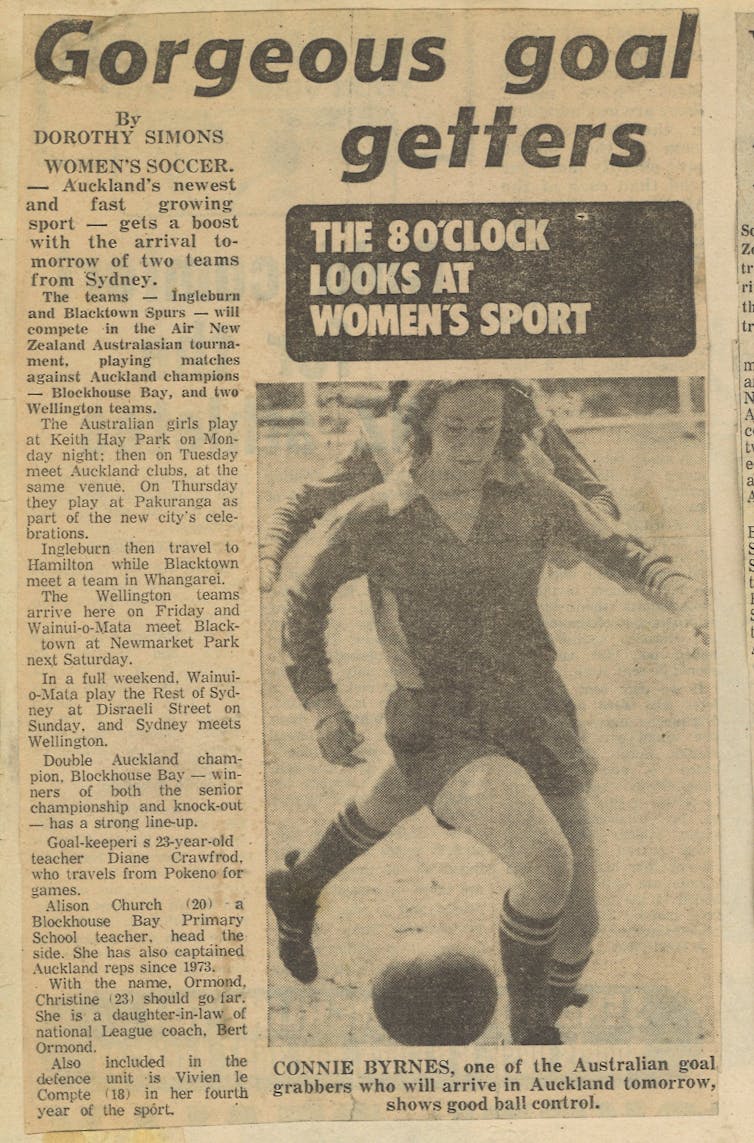

The press coverage had recurring themes around appearance, fashion, body parts (especially eyes, legs and hair), sexual attractiveness, implied sexuality and general unwelcome sleaze.

Even a neutral match report would attract a sub-editor’s headline such as “Gorgeous goal getters” or “Fashion on parade at Australian titles”.

Captions to newspaper photos suggested their skills were more about dance than soccer. Press photographs were selected to reinforce this view: “Booted ballet”; “Shall we dance – cha, cha, cha”; “Remove the boots and these ladies could be doing the hustle, the bump or any of the other dance crazes sweeping the nation”.

Male journalists reported the women, although skilled, were “easier on the eye” than their male counterparts.

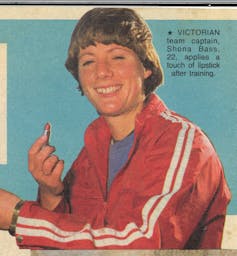

Players were asked to apply make-up after training for photographers. Femininity was emphasised.

Author provided

In one article, New Zealand coach Dave Boardman rejected the label his charges were “butch types”.

“They are delightful young ladies,” he said.

The men involved in soccer played by women – the coaches and the referees – were portrayed in news articles as active and in charge. Their opinions mattered most to the press.

Player Pat O’Connor was one of the driving forces behind the growth of soccer in New South Wales, alongside her husband and coach Joe O’Connor. In one article about Pat, the journalist wrote: “Striker Pat has to obey her husband!”

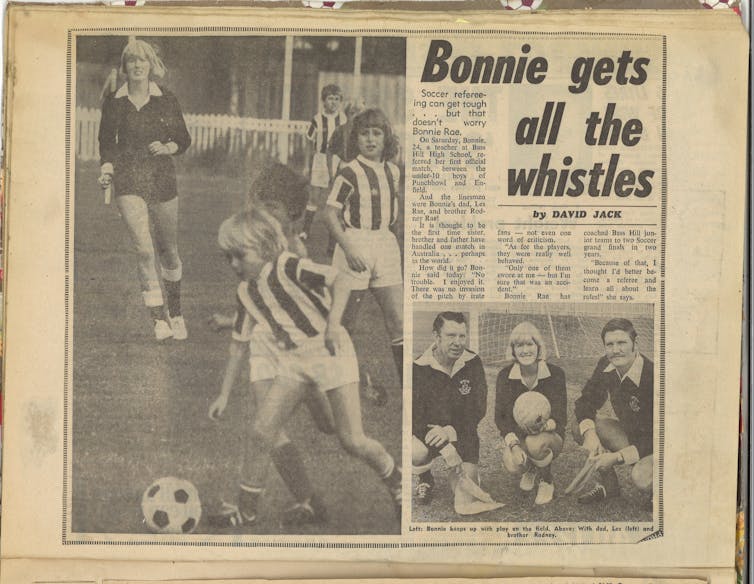

When 24-year-old Bonnie Rae qualified as a referee, the headline read: “Bonnie gets all the whistles”.

Author provided

AFL legend Lou Richards, commenting on the Victorian team, wrote he wanted “to have a cuddle with those pretty little soccerettes after every score […] I’d be quite willing to act as official trainer and masseur”.

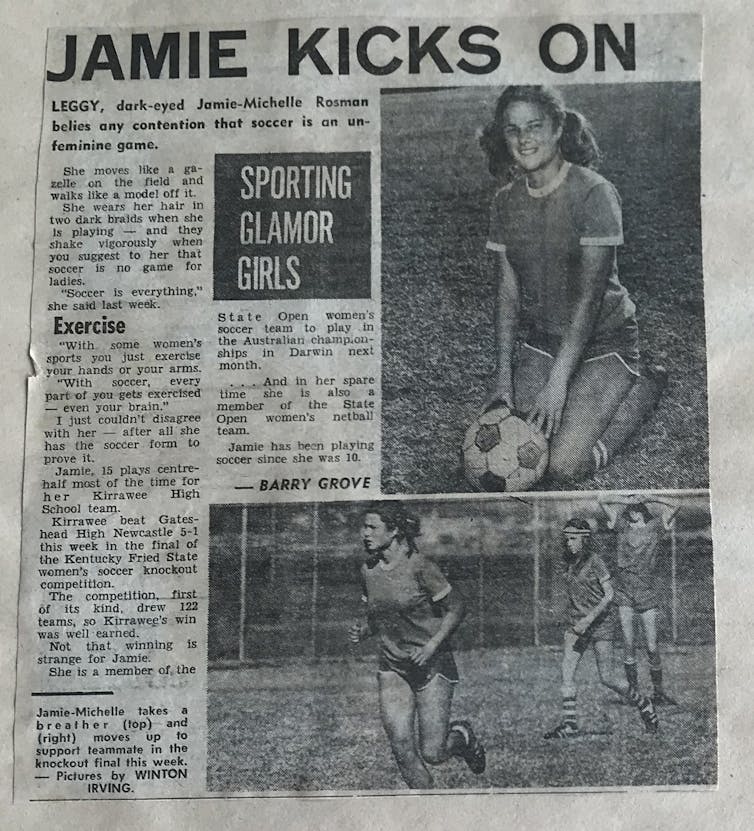

The schoolgirls in the national teams were not spared. Jamie Rosman, just 15 when she was playing for Australia, was described as “attractive”, “leggy” and “dark-eyed”, “a gazelle” and “a model”.

Author provided

Being in the zone

The articles in these scrapbooks are a toxic time capsule of sexism, misogyny and veiled homophobia. They remind us just how difficult it was for women and girls to navigate a safe space for themselves in soccer in the eyes of the public.

Good football players say they block out noise and play in a bubble – the “zone”. Is this the way the women also coped with the toxic media coverage of their soccer? Does this partly explain hazy memories of the first series in 1979?

When we spoke to the players about their scrapbooks, they recalled often feeling uncomfortable in their interactions with the press. Shona Bass said “I walked away with this unease about the way they had portrayed us […] it was almost patronising, almost scoffing”.

As the Matildas and the New Zealand Ferns move into hosting a historic home world cup, we can look forward to today’s media demonstrating a far greater maturity and higher level of respect.

From ‘girls’ to Lionesses: how newspaper coverage of women’s football has changed