Millions of years of isolation have shaped Australia’s extraordinary mammal fauna into species unlike anywhere else in the world, from platypus to koalas and wombats.

Tragically, Australia is the world leader in mammal extinctions. About 40 species have gone extinct in the 238 years since European colonisation began, and nearly 80 species are now imperilled. It’s essential we understand what factors caused these extinctions and ongoing decline.

Over many years, scientists have gathered compelling evidence demonstrating predation by introduced cats and foxes has been a key driver. Australian mammals have had millennia living alongside other predators such as wedge-tailed eagles and dingoes. But foxes and cats are extraordinarily capable and ecologically flexible hunters, quite unlike anything Australia’s mammals had confronted before.

Recently, some researchers have questioned whether these introduced predators really are responsible. In our new research, we lay out the clear lines of evidence implicating foxes and cats. For instance, extinct species tend to be small-to-medium mammals, the preferred prey size for these predators. When mammals are returned to fenced, fox- and cat-free areas, their populations often flourish.

Author provided, CC BY-NC-ND

Controversy in conservation

Last year, researchers questioned whether there was enough evidence to say feral cats and foxes had contributed to Australian mammal extinctions – and, by implication, their role in the ongoing decline of other threatened mammal species.

Their research drew on three premises relating to extinct and surviving mammals. If cats and foxes caused these extinctions, they argued that these should follow:

The last recorded sighting of a now extinct mammal from an area must come after the arrival of one or both of these predator species

Lethal management programs aimed at reducing fox and cat numbers should result in an increase in native mammal numbers in an area

Where cats and foxes are abundant, there should be fewer native mammals.

After testing these three ideas, the authors conclude the hypothesis foxes and cats cause extinctions “has come to be accepted with little evidence.”

The research caused a major stir among the conservation community, as it took aim at longstanding accumulated knowledge and questioned whether the evidence base was strong enough to justify efforts to control feral cats and foxes.

As experts with many decades experience working to protect threatened Australian mammals and other wildlife, we had a duty to evaluate their evidence.

Claim and counterclaim is essential to test, shape and hone science, and to provide a robust foundation for conservation management. It may seem like an academic argument, but it has clear real-world implications.

The survival and recovery of much of Australia’s native mammal fauna depends on controlling cats and foxes. Many recent success stories in bringing native animals back from the brink are due to removing foxes and cats.

If this objective is abandoned because of arguments feral cats and foxes are simply innocent bystanders, we risk rapidly losing many of these imperilled species.

Neil Bowman/Getty

What did we do?

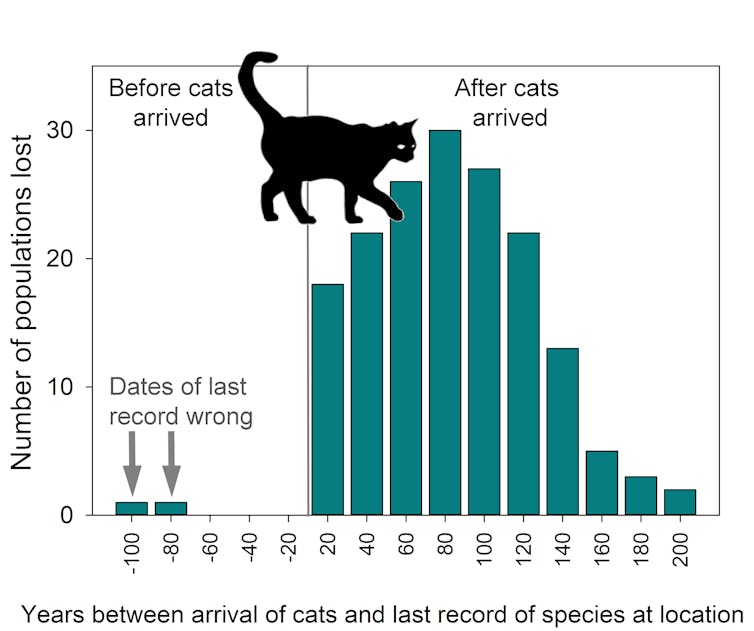

A provocative claim in last year’s research was that some Australian mammal species may have gone extinct before foxes and cats ever got to the area. If this was true, cats and foxes couldn’t be held responsible.

Cats came with the First Fleet in 1788, augmented with many subsequent introductions. By the 1890s, feral populations had spread across the entire continent. Foxes came later, first introduced to southeastern Australia in the 1830s. They, too, spread out across most of the continent over decades.

We re-ran analysis of the historic data and found the last record of a now-extinct native mammal in an area was always dated after the arrival of cats. The picture is less clear for foxes, though this is understandable given the earlier arrival of cats would already have caused losses.

Further, the actual date of extinction may occur long after the last documented record, especially in remote, sparsely populated areas of Australia.

First Nations peoples and Europeans have witnessed and recorded many cases where a native mammal species disappeared from an area soon after one or both non-native predators arrived.

Fate provides further evidence. Many mammals were wiped out from their entire mainland ranges but survived on islands that cats and foxes never colonised. For instance, all mainland populations of the greater stick-nest rat have disappeared. But the species survives because it also had an island population. By contrast, the lesser stick-nest rat had no island population. It is now extinct.

Author provided, CC BY-NC-ND

Does fox and cat control work?

The authors argue fox and cat control doesn’t result in increases of threatened mammals. But this conclusion may stem from misreading data from feral cat and fox control programs. Not all control programs work to reduce cat numbers over long periods or even at all.

Instead, we can get far clearer evidence from what happens in safe havens – islands or fenced areas where foxes and cats are completely excluded. Threatened mammal species almost always increase in these areas and almost always decline at comparable sites where foxes and cats are not excluded.

Eastern barred bandicoots now roam Victoria’s fox-free Phillip Island, while hare-wallaby numbers are rebounding on Western Australia’s Dirk Hartog Island following the eradication of feral cats.

The assumption that native mammals should typically be less abundant when and where cats and foxes are more common doesn’t always hold. After periods of good rainfall in inland Australia, populations of native mammals and feral predators all increase. During droughts, predator and prey numbers both fall.

Katherine Moseby, CC BY-NC-ND

Difficult truths

The original analysis and our new research have a broader context. Some have argued the impact of introduced species has been overstated, and that introduced species should be seen as a legitimate part of Australia’s ecosystems. Scientific evidence and conservation outcomes do not support this.

Australia supports about 8% of the world’s biodiversity as one of just 17 megadiverse nations. Protecting our unique species is not easy. But the task for conservationists and policymakers will be even harder if feral cats and foxes are given a free pass to keep killing.

Lethal control is, unfortunately, necessary to protect many species near the brink of no return. It has to be done as humanely as possible and justified publicly. Stepping back would mean more and more extinctions.

We would like to acknowledge our research coauthors.