After wrapping up a recent four-day trip to China, United States Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told a media briefing: “We believe that the world is big enough for both of our countries to thrive.”

While optimistic, Yellen’s statement is far from persuasive. It doesn’t represent the tense geopolitical landscape saturated with sanctions, investment restrictions and containment efforts.

Yellen’s was one of many visits by U.S. officials to China in recent months. These overtures come on the heels of concentrated American efforts against what the U.S. perceives to be China’s increasing expansion and assertiveness in Asia. President Joe Biden’s administration has made its intentions clear about maintaining the status quo in Asia, and Beijing is responding cautiously.

How did relations between the U.S. and China become so antagonistic over the last decade?

Conflicting policies

In a news conference with Chinese President Jiang Zemin in 2002, then President George W. Bush said: “China’s future is for the Chinese people to decide.” But the current state of relations indicates the path the Chinese chose for themselves is not sitting well with the U.S.

In 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton suggested the Barack Obama administration wanted to go further than Bush had in developing the China-U.S. relationship:

“We need a comprehensive dialogue with China. The strategic dialogue that was begun in the Bush administration turned into an economic dialogue.”

The Obama-era approach then culminated in a comprehensive pivot to the Asia-Pacific region in 2011 that resulted in American economic, security and diplomatic resources shifting towards the area.

During Donald Trump’s administration, U.S. policy priorities on China shifted back to economic relations as the trade deficit between the two nations became a central point of contention. The Trump approach was no longer dialogue, but rather direct confrontation.

The China-U.S. conflict is about much more than trade

Under Biden, China is deemed a “competitor.”

Policy choices have included reducing economic dependence on Chinese supply chains, the creation of the Australia, United Kingdom and United States partnership known as AUKUS and gaining U.S. access to four additional military bases in the Philippines.

Chinese pragmatism

While America’s China policy has transformed into confrontation, China’s overall foreign policy trajectory has largely been pragmatic and linear.

Since the 1990s, China has been explicit in its grand objective of a multi-polar world in which global politics is shaped by several dominant states.

When Xi Jinping ascended to the presidency in 2013, this aspiration became increasingly overt and assertive. A year earlier, Vice-President Xi announced China’s “two centennial goals” — one calling for China to be “prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious and beautiful” with influence over the global world order by 2049.

(AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

To analyze Chinese-American relations, the metaphor of the Thucydides’ trap — in which a rising power challenges an existing one — may not be the most appropriate analogy. And phrases like “the rise of China” don’t do justice to China’s history.

China has been a great power, regionally at least, for thousands of years and was a manufacturing behemoth even in the 1750s.

Geopolitically, the U.S. continues to retain a military and diplomatic edge over China. It has demonstrated its will and capability to determine the rules of engagement in China’s own backyard.

But even though China trails the U.S. in many areas, it doesn’t need American support as much as it used to. Astonishingly rapid development in the last two decades is probably still far from China’s most creative and innovative phase.

NATO should tread carefully in Southeast Asia, where memories of colonialism linger

American limitations

There are also limits to the American field of influence in the region.

The U.S. has failed to move beyond strengthening existing alliances and fortifying its military installations. Its geo-strategic options are also limited. If, for example, the Americans shored up Japan’s offensive capabilities or deepened their partnership with India to challenge China, they would be inadvertently creating a multi-polar world.

China is not deterred by American policy. It is countering it through the art of persuasion and dialogue. But it too has exhibited its limits.

With a few exceptions, China has failed to convince even its neighbours of the sincerity of its intentions. A majority of Asian nations are either U.S. allies or neutral.

The ongoing tit-for-tat between the two nuclear and highly interdependent powers will continue to shape their relations, which is concerning for global peace and stability.

Will the U.S. peacefully share global influence with China? Will China abide by its Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and its claim that it will never seek world domination? It’s hard to say.

Four indicators of what lies ahead

Several indicators, however, point to a somewhat balanced co-existence between the two as dominant power centres in the coming decades.

First, the U.S. has been unsuccessful in inhibiting China’s growth and expansion, and will likely be incapable of preventing the second-biggest economy from achieving its centennial goals.

Second, China is already present around the globe in terms of human capital, investment, manufactured products — and world public opinion about China is changing.

Third, to use the Taoist metaphor, China is a hub that has many spokes and has the capacity and will to invent many more. The hub is united and efficient; an economic downturn will only slow the social organism, not cause it to collapse.

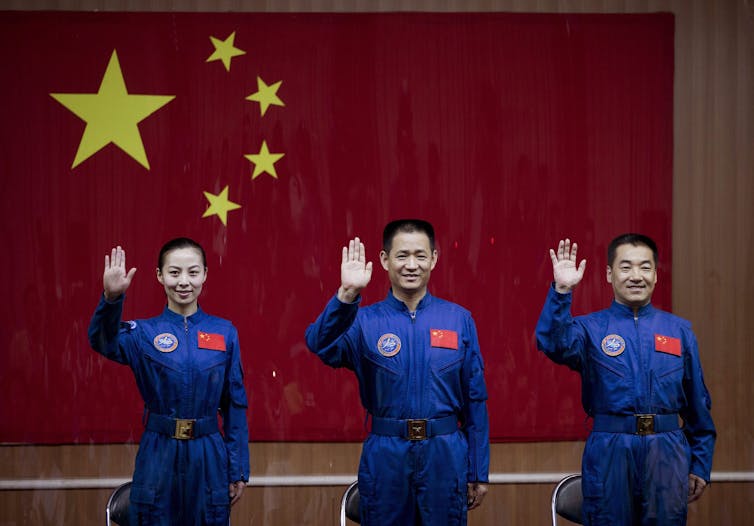

When China was barred from the International Space Station after the passage of a law by U.S. Congress in 2011, for example, it constructed Tiangong, a permanent space station.

(AP Photo/Andy Wong)

Fourth, the rise of non-liberal democratic regimes and weaknesses in democracies are creating a situation where some nations are gravitating towards China while others are moving away from the U.S.

Trump-fuelled chaos shows democracy is in trouble — here’s how to change course

That said, political reason is too often at the mercy of short-term calculations.

The U.S. has shown no interest in sharing world leadership, nor has China shown any interest in deviating from its global aspirations. But even though they may appear to be on a collision course, it seems likely China is going to be successful in its pursuit, and both nations will ultimately learn to co-exist and thrive.

Until then, one can only hope that they spare the world the chaos and ugliness of power politics and use their creative energies for the betterment of the human condition.