Wulf and Eadwacer occupies just a few lines in the Exeter Book, an anthology of mostly anonymous Old English poems made in the second half of the 10th century. As a relic of a literary culture largely lost, the Exeter Book is priceless. But some of its contents are very hard to understand.

This includes Wulf and Eadwacer. The poem’s first editor said in 1842: “Of this I can make no sense.” Over 100 studies later, not much has changed.

The poem seems to be spoken by a woman, lamenting her relation to two men, Wulf and Eadwacer, in some unknown watery landscape with islands. She also mentions a “whelp”, often supposed to be her child by one or other of them, or neither. If you think that sounds clear enough, every point could be – and has been – disputed by scholars.

It is also usually included among the Old English elegies, a handful of untitled poems also in the Exeter Book, which speak of the sorrow of unidentified men and women undergoing separation, persecution, hardship, exile and imprisonment. Sadly, nobody agrees on what or who they are about either.

But at least Wulf and Eadwacer has names. And in a recent paper in Anglia, I argue that these enable us to crack the poem’s code.

The road to revelation

Over 100 years ago, the medievalists Henry Bradley and Israel Gollancz suggested that the name Eadwacer was the Anglo-Saxon version of Odoacer, a Germanic general in the Roman army who deposed the last western Roman emperor in 476 and made himself king of Italy.

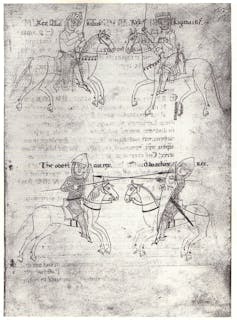

Chronica Theodericiana

Gollancz also suggested that Wulf was Odoacer’s enemy, Theodoric the Ostrogoth. As there seemed to be no literary parallels, his theory was, and remains, ignored.

Maybe so, I thought, but what if we look at the historical record? No one had done this before. It proved a revelation.

I read chronicles in Latin and Greek which described the war between Odoacer and Theoderic, culminating in the Theoderic’s siege of Odoacer’s northern Italian capital, Ravenna.

This ended with an agreement that the men would live and rule together in the city. But after only a few days Theoderic murdered Odoacer (at a feast, according to one historian) and then all his family and followers.

I found it remarkable that no one had mentioned the resemblance of the poem’s landscape with the topography of Ravenna, a fortress city surrounded by a lagoon dotted with islands. More significantly, this siege was the subject of medieval German poetry about Theoderic, in which he was known as Dietrich, which was well known to students of German literature.

In one German text, Dietrich had been exiled by his villainous cousin Odoacer and after 30 years returned to Ravenna to seek his revenge.

© British Library Board, CC BY

The language of Wulf and Eadwacer’s opening lines with their vague hints at conflict and threat had always been found bafflingly obscure. But now it seemed clear that they described the end of the siege.

Eadwacer (who was Odoacer), king of a starving city, entices Wulf (Theoderic), encamped in the lagoon, with what the female speaker sees as treacherous intent.

She uses the rare Old English verb aþecgan to describe the reception awaiting Wulf. Puzzlingly, this meant either “to welcome” or “to eat”. But now we could see that the deft poet had both meanings in mind (Ravenna was starving, and remember that historian’s feast?).

I also showed that “Wulf” was likely to be an assumed name suited to an outlaw – a “wolf’s head” in Old English – and to a clandestine, predatory lover in other comparable texts with wolf motifs.

Unravelling the mystery of Eadwacer’s starving wife

But the penny did not really drop until I came across a source that nobody else had linked to the poem: a seventh century Greek chronicle by John of Antioch.

In John’s account, Odoacer has a son called Okla, who was given as a hostage to Theoderic and later killed by him. Here was the “miserable whelp”.

Not only that, but John (uniquely) provided Odoacer with a wife. Named Sunigilda, she had been imprisoned and – this was the most startling correspondence with the poem – starved to death by Theoderic.

This was the last piece of the jigsaw. It explained for the first time that the speaker in Wulf and Eadwacer must be Eadwacer’s wife. She was sequestered on an island, evidently by her husband. And she cried out to him that it was her longing for Wulf (her lover) that was making her ill, not meteliste, “desire for food”.

In John’s history, it was Theoderic who had been her captor. But in the literary tradition which turned Theoderic into the hero Wulf, her tormentor was now her husband Eadwacer.

© British Library Board, CC BY

This, I argue, is an interpretation which provides the first complete account of the names, characters and scenario of the poem, the sole remaining example from Anglo-Saxon England of poetry about the heroic Theoderic, a subject which was previously thought to have survived only in literature from the continent.

The poem’s language and imagery are no longer obscure, but full of skilful wordplay and layers of meaning. Wulf and Eadwacer is an intense exploration of divided loyalties, unsatisfied longing and transgressive hatred at a turning point in the history of the Goths and Europe.

Feminist critics had highlighted the importance of the speaker of the poem being a woman. They were right to do so.

Here, possibly four centuries before women are given a significant voice in heroic poetry in Germany and Scandinavia, a queen speaks out in an English version of a Gothic story. And she can be given a name too. The Anglo-Saxon version of Sunigilda was Sonegild.