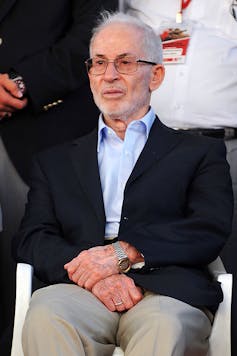

Ibrahim Munir, the leader of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, died on Nov. 4, 2022, in exile in London. While the news generated few headlines around the world, Munir’s death marks a critical moment in the evolution of a group founded nearly 100 years ago, as a social and religious movement.

Over the years, the Brotherhood grew into the most significant social movement and political opposition in Egypt. Its Islamist ideology – which calls for public policies in line with its interpretation of Islam – became widely influential around the world.

But since a 2013 military coup that removed the Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate Mohammed Morsi from power, the group has been all but destroyed, with most of its leaders either imprisoned, killed or in exile.

For now, the group has a new temporary leader in Muhyeddine al-Zayet, a 70-year-old senior figure in the movement.

But the stark reality is that the Brotherhood is at a turning point: The movement either will have to reinvent itself or face the prospect of gradually fading into irrelevance.

As a scholar of social movements who has studied the evolution of the Brotherhood and interviewed both members and defectors, I believe its fate hangs on three issues: how it responds to Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s repression of opposition groups including the Brotherhood; which leaders guide the movement during its crisis; and how the group rebuilds in exile.

Has the Brotherhood run its course?

The Muslim Brotherhood was established in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna, a primary school teacher with a vision that piety and Islamic values can help transform the individual, reform society and ultimately bring about an Islamic state.

Appealing to Egyptians disillusioned with the country’s existing religious institutions, critical of its political system and angered by the Western interference in the Muslim world, the Brotherhood grew into a grassroots movement with an intricate network of schools, newspapers and social services.

By the end of the 20th century, the Brotherhood dominated civil society in Egypt and became a prominent source of political opposition. It also established branches and affiliates throughout the Muslim world.

Following the 2011 Arab Spring, which saw popular uprisings in a number of countries across the Middle East, the Brotherhood came to power in Egypt’s first free and fair elections. Its affiliated political party, the Freedom and Justice Party, won the largest parliamentary block, and its candidate, Mohammed Morsi, was elected president. By June 2013, however, disillusionment with the lack of political progress and the poor economic performance of the country led to widespread popular mobilization against the Brotherhood. A month later the military ousted Morsi from power.

Emergence of two Brotherhoods

When Brotherhood supporters took to the streets and demanded that the democratically elected president be reinstalled, police and army forces opened fire on demonstrators. On Aug. 14, 2013, security forces brutally put down the sit-in in Rab’a Square in eastern Cairo, killing over 800 people, in what Human Rights Watch said likely amounted to crimes against humanity.

For some Brotherhood members, the brutality of the security forces sparked a desire for revenge and justified a violent response.

For the most senior Brotherhood leaders, however, violence was neither politically pragmatic nor ideologically justified. In the absence of a clear vision for how to respond to the political crisis, many young members became disillusioned with the organization.

By 2014, the Brotherhood was not just losing members. Two additional fault lines emerged: the question of leadership and the question of exile. Mass arrests caused a leadership vacuum that led to a new cadres of midranking members taking over activities inside Egypt.

These new leaders adopted a more revolutionary tone and started operating independently of the older leadership. The parallel claims to authority and divergent visions over how to respond to the political repression led to a split between the so-called “historical leaders” and the new leadership.

Ozan Kose/AFP via Getty Images

By 2016 there were in effect two Muslim Brotherhoods: the original group, under the leadership of Ibrahim Munir as the deputy guide operating out of the U.K., and the so-called “General Office,” under the new leadership. The General Office attracted many young revolutionaries, including women, but the group had significantly fewer resources, which led it eventually to dissipate.

I learned from interviews with Brotherhood members that with Munir operating as leader in exile, a deeply contested internal debate emerged over whether to restructure the movement and shift the strategic decision-making to the leaders abroad. Outside of Egypt, the organization established regional consultative councils in most host states with a significant Brotherhood presence, most notably in Turkey.

While this allowed for some semblance of organizational rebuilding, some leaders still insisted that all major decisions about the direction, tactics and strategies of the Brotherhood be made inside Egypt.

Can the Brotherhood rise again?

This is not the first time that the Muslim Brotherhood has been nearly destroyed by government repression. In 1954 a militant faction of the Brotherhood allegedly attempted to assassinate Prime Minister Gamal Abdel Nasser, prompting a severe crackdown on the group. The torture and abuse that Brotherhood members faced in prison inspired a new militant vision for activism and led a small group of Brotherhood members to start plotting attacks on government officials. The government discovered these cells before any plans came to fruition, leading to a second major wave of repression in 1965.

But the circumstances in which the Brotherhood finds itself today are different from these past periods of repression. It is more deeply divided than before. And importantly, the current repression comes after the movement came to power and had a chance to rule but ultimately failed.

The Arab Barometer, a nonpartisan research network, shows that since 2013 Egyptians have been consistently skeptical of political Islam as expressed by the Brotherhood, even as the population remains largely religious. For for many of Egypt’s young people the Brotherhood cannot offer any solutions to the economic hardships facing the country, or the growing human rights abuses.

Faced with these internal divisions and challenging political circumstances, the road ahead will not be easy for the Brotherhood. As some of its former members have admitted, there is a tension between being a social movement and being a political party.

The Brotherhood knows that many Egyptians agree with the group’s religious values at the same time that they are deeply critical of its political ambitions.

If the Brotherhood seeks to become a force of change again and attract a new generation of Islamist activists, I believe it needs to develop a new vision and theory of political agency that inspires both the youth in exile, who speak the language of inclusion, diversity and revolution, and Egypt’s young people, who hunger for freedom and economic opportunities.