In March 2023, a Utah woman named Kouri Richins published a children’s book titled “Are You With Me?” which she characterized as an effort to help her three young sons process the loss of their father, who had died suddenly the previous year. Presenting herself as a concerned mother and grieving widow, she was interviewed on “Good Things Utah” in April 2023.

A few weeks later, on May 8, 2023, Richins was arrested and charged with killing her husband, Eric.

An autopsy showed that the 39-year-old man died of a massive fentanyl overdose. Since Eric had no history of drug abuse, his family found the circumstances suspicious. In the months before his death, Eric confided in his business partner that on several occasions – after being served a drink or meal by his wife, including on Valentine’s Day – he had become violently ill. Utah’s Park Record reported that he had mentioned to friends and family that if anything were to happen to him, Kouri would be the likely culprit.

In August 2023, as I write this, the Richins’ housekeeper has confessed to providing the fentanyl that killed Eric, and the case is mired in multiple lawsuits, including one in which the victim’s sister accuses Kouri of “enacting a horrific endgame to steal money from her husband, orchestrate his death and profit from it.” Meanwhile, Kouri Richins refutes these charges and has filed her own civil suit “seeking not only half of the marital residence but also her late husband’s business, which is valued at approximately $4 million.” She has been denied bail and is currently awaiting trial – an event destined to become a media spectacle.

Whether or not it’s true that “each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” as Leo Tolstoy famously wrote, other people’s domestic misery seems to be a constant source of interest.

What lies behind the public’s fascination with familial trauma, especially when it turns deadly? And what occluded anxieties or longings do people confront or exorcise as they consume these stories of mayhem and murder?

The interest in true-crime podcasts, series and documentaries is nothing new. The public appetite for easily accessible portraits of real-life murders stretches back to the early days of print, when they were repackaged and sold as ballads, domestic tragedies and lurid penny pamphlets.

My research as a scholar of 16th- and 17th-century English literature is largely focused on popular representations of domestic crime. I’m often struck by the resonance between these historical portrayals and the way such incidents are reported today.

While the medium has changed, the framing of these stories has remained strikingly consistent. The same queasy combination of sensationalist titillation and pious condemnation found in 16th- and 17th-century media appears in today’s news coverage of domestic murders – and it shines a light on enduring cultural anxieties.

‘Sleeping in a serpent’s bed’

The Richins case – with its themes of marital distrust, betrayal and conflicting interests – echoes a 16th-century murder so scandalous that it was reported in historical chronicles and popular pamphlets alike. It also inspired the Elizabethan domestic tragedy “Arden of Faversham” and at least one ballad.

The crime occurred on Valentine’s Day 1551, when Alice Arden conspired with her lover and some hired assassins to kill her husband, Thomas, at his own dinner table.

The historical records and the play depict a woman who places desire above duty, determined to kill her husband and replace him with her paramour, who was a servant in her stepfather’s household – a step down the social ladder that added insult to injury.

That the murder of a middle-class suburban bureaucrat rated inclusion in official sources like “Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland” and the “Newgate Calendar” – and was still inspiring fresh interpretations decades later – suggests an appeal beyond the merely salacious.

Newcastle University

In 16th-century England, where the majority of adults were married, women effectively became their husbands’ legal “subjects” upon marriage. This meant that a wife who killed her spouse was guilty not only of murder but of petit, or “petty,” treason, a crime against the state punishable by burning. As I have argued elsewhere, the idea of violent marital insurrection posed a frightening challenge to patriarchal notions of a man’s home as his castle.

But cases of female violence were – as now – comparatively rare: The figure of the murderous wife wielded far more power in the imagination than in reality.

As the unmarried Elizabeth I’s long reign drew to its close, fears about domestic partners gone wild indicated broader fears about the family as a “little commonwealth” or microcosmic state – and the need to reinforce the status quo in politically uncertain times.

In life and onstage, Alice Arden was the stuff of proto-feminist fantasy and masculine nightmare, and early modern plays, pamphlets and ballads sought to defuse the rogue woman’s perceived menace in the way they presented the scandal.

In the play, Alice’s lover, Moseby, notes that “‘tis fearful sleeping in a serpent’s bed,” since when she has “supplanted Arden for my sake” she might “extirpen me to plant another.”

These suspicions find an echo in Eric Richins’ fears about his wife’s intentions, and in some media portrayals of her as a thwarted gold digger.

‘Like a fierce and bloody Medea’

If a homicidal wife was a terrifying prospect, a murderous mother presented an entirely different level of horror.

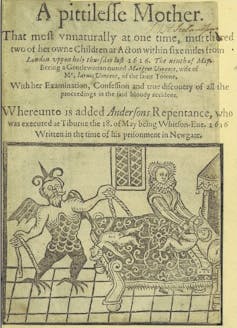

The anonymous 1616 pamphlet “A Pittilesse Mother That at One Time Murdered Two of Her Own Children at Acton, etc.” tells the story of Margaret Vincent, who strangled and killed her two young children in an attempt to save their souls when her husband refused to convert to Catholicism. (She later repented, saying she had been “converted to a blind belief of bewitching heresy.”)

British Library

There are many parallels in the stories of Vincent and an evangelical Christian named Andrea Yates, who in 2001 drowned her five children in the bathtub of their Texas home, believing she would send their souls to heaven and drive Satan from the world. In March 2002, Yates was sentenced to life in prison, but a 2006 appeal found her not guilty by reason of insanity. She now resides in a mental health facility from which she routinely refuses to apply for release.

Neither Vincent nor Yates had been involved in any previous crimes or scandals, but both had exhibited signs of spiritual or mental instability. Vincent had “disobediently” insisted her family become Roman Catholics; Yates had stopped taking the medication prescribed for her postpartum depression and later psychosis without her doctor’s approval. Both women reportedly planned their children’s murders carefully, waited until their husbands were away from home to commit them, invoked diabolical forces to explain their actions, and initially claimed to feel no remorse.

The correlation between these historically distant murders is disturbing and fascinating, not least because both narratives feature conventionally “good,” married, middle-class mothers. Yet both were excoriated in contemporary media as monsters: guilty of crimes against nature, their husbands and their offspring.

Fast-forward to Jan. 24, 2023, when Lindsay Clancy sent her husband, Patrick, on an errand and, like Margaret Vincent, strangled her three children before attempting suicide.

When Patrick Clancy returned to their home in Duxbury, Massachusetts, he found Lindsay on the lawn with major injuries, suffered in a jump from a second-story window. Inside, his children – ages 5 years, 3 years and 8 months – were unconscious. The two oldest were pronounced dead at the scene, while the youngest survived for several days.

As more details of the case became known, a picture emerged of a doting mother and nurse midwife who often shared family photos and anecdotes on social media. After her youngest child’s birth, these posts included references to depression, anxiety and her ongoing attempts to find relief via therapy and medication.

The inevitable comparisons to the 2001 Yates murders were exacerbated by her lawyer’s revelation that Clancy had been prescribed more than a dozen medications in recent weeks, and by her own claim – as reported during her Feb. 7, 2023, arraignment – that she had “heard a man’s voice, telling her to kill the kids and kill herself because it was her last chance.”

David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The prosecution presented Clancy as a coldblooded, calculating murderer. The defense countered with a portrait of a woman suffering from serious mental illness with inadequate treatment. Patrick Clancy has argued that his wife deserves compassion rather than condemnation.

As the familiar lines are drawn on the battlefield of public opinion, the sense of déjà vu is palpable. Is Lindsay Clancy a latter-day Medea, the vengeful child killer of Greek mythology, or an overwhelmed and poorly supported woman struggling with a serious illness? As of this writing, Clancy is committed to Tewksbury State Hospital until November 2023, at which point future legal proceedings will be assessed.

These events are unquestionably horrific, but the passage of two decades may have wrought some changes in the public’s response. While Clancy has been reviled in some quarters as a coldblooded killer – particularly on social media – the murders have also sparked a discussion about postpartum mental health, suggesting a willingness to better understand this complicated topic.

A queasy sort of comfort

Tales of domestic murder expose and underscore fears about society’s most fundamental institutions: home, family and community. The media in every period are extremely skilled at weaponizing – and capitalizing on – worries about the family’s capacity to provide a safe haven in a turbulent world.

In early modern England, highly gendered ideas about the home as a reflection of the state politicized anxieties about order, stability and the family as a patriarchal institution. Then as now, it was a frightening – yet compelling – prospect that threats to a family’s very survival might be hiding in the place people should feel safest.

Perhaps the ongoing fascination with dysfunctional, broken homes is based in schadenfreude, and the comforting realization that as troubled as our own families may be, we have not taken violent action against them.

Like the repentant gallows speeches recounted in ballads, or the assurance in “A Pittilesse Mother” that Margaret Vincent “earnestly repented the deed,” the containment and punishment of those who disrupt this bedrock institution offer reassurance that they are anomalies. (I could never do that; you could never do that.)

Or the appeal may lie in the idea that any of us might, in fact, be capable of such things.

Perhaps in choosing to be disturbed, entertained and ultimately comforted by narratives about domestic stability turned to chaos, we find a way to confront, if only obliquely, our most primal fears about the institutions we trust, the people we love – and our own capacity to destroy them.