Taylor Swift recently removed a scene from her music video, Anti-Hero, after several fat positivity activists across social media accused the scene of being fatphobic.

In the scene, Swift’s two selves, the real her and her “anti-hero” character, are in a bathroom. As Swift’s real self stands on a weighting scale, her anti-hero persona peers downward and the word “FAT” appears on the scale. Swift’s face appears disgusted. The scene earned considerable backlash online.

In response to the video, fat positive therapist Shira Rosenbluth posted on Twitter:

Taylor Swift’s music video, where she looks down at the scale where it says “fat,” is a shitty way to describe her body image struggles. Fat people don’t need to have it reiterated yet again that it’s everyone’s worst nightmare to look like us.

White celebrity feminism

As white feminist scholars committed to anti-racist and decolonial practices who work on divisions within feminist politics as they appear in art practices, this is far from an isolated incident of one artist. It reveals divisions about fat positivity within white feminism.

White feminism is not just an identity, it is a structure. As women’s studies scholar Kyla Schuller writes, it “attracts people of all sexes, races, sexualities and class backgrounds, though straight white middle-class women have been its primary architects.”

(YouTube/Taylor Swift)

Fat activists have worked to take power away from the term “fat” and use it as a neutral descriptor. Swift does not believe she is fat, but is illustrating internalized fatphobic messages. According to Swift, fame and public scrutiny of her body was a major contributor to her eating disorder.

Some have raised concerns that Swift’s removal of the scene from the video watered down her feminist message. But how does removing the term “fat” water down a specifically feminist message unless fat is seen to be a feminist issue?

This suggests that fat becomes a feminist issue only in the context of the harms of eating disorders from a white woman’s perspective, within market-friendly celebrity feminism.

Fat activists are criticizing Swift’s video and response for reproducing a depoliticized and individualistic strain of feminism that ignores the racial, colonial, ableist and socioeconomic problems behind issues such as eating disorders.

Swift has been able to deflect criticism with the support of fans and media writers who have jumped to her defence to protect her image.

Erasure of others’ experiences

Online responses to fat activist critique is telling. Swift’s defenders dismiss and demonize fat activists, aligning them with stereotypes of fat women as unruly.

As feminist scholar Alison Phipps argues, white feminism is an identity deeply invested in victimization, suffering and injury.

Swift’s silence and her angry defenders reveal a complicity in reproducing white supremacist fatphobia.

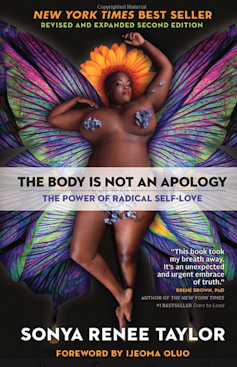

(Penguin Random House)

The rhetoric erases the fatphobia experienced by Black women and other racialized people. As author Sonya Renee Taylor writes, “From LGBTQIA bodies, to fat bodies, to women’s bodies, we live under systems that force us to judge, devalue, and discriminate against the bodies of others.”

White feminism upholds the idea that feminism is about individual empowerment, letting artists off the hook of answering for the injustices reiterated in their art. Moments like this come up regularly in feminist politics and rejecting a fat activist critique is a missed opportunity for coalition. It reinforces the power of white feminism to gatekeep.

Feminism and eating disorders

This division between feminism and fat activism often revolves around conceptualizing the harms of eating disorders. Feminists have argued that eating disorders do not exist in a social or cultural vaccuum, but this argument has stopped short at fat acceptance. Fat positivity requires grappling with how our culture is obsessed with thinness, and how it reviles fatness as a way of enforcing and maintaining bodily hierarchies.

Swift’s video echoes many other white feminist artists who work out their bad body feelings in public as a way of processing harms of a negative body image.

A running theme in Swift’s work is to mock media misogyny. Since distancing herself from authentic country storytelling, she has moved to a pop persona that relishes in her “zany” flaws and talks about the “real person” underneath the persona to remain relatable. Here, fatphobia is a personal flaw rather than a systemic social issue.

White feminist responses to fat activist critique reveal the limits of fat positivity in feminism. Women’s studies professor Talia Welsh articulates how mainstream feminism is of two minds:

[The feminist] ability to reject the demonization of fat in one context and to accept fat’s negative status in another is based in the idea that one view of fat (the bad one) arises from sexism and that the other (the good one) arises from a concern about health. It is wrong to equate a woman’s value with her looks, but it is acceptable to encourage that same woman to lose weight if it would augment her health.

Swift’s permission to express fatphobia in terms of it being detrimental to her health upholds her victim status, thereby centring a thin woman’s pain in discussing fatphobia.

The message received is: feeling positive about one’s body is good, but that good has limits, it is only for those with thin bodies.

Swift has no doubt been the target of beauty culture’s critique, but that culture cannot be divorced from its capitalist, colonial and white supremacist roots. In identifying fatphobia as primarily about women’s looks, Swift and others obscure the structural and material oppression experienced by fat people

These divisions in feminism will continue so long as white feminism claims fatphobia as its issue to both define and individually resist.