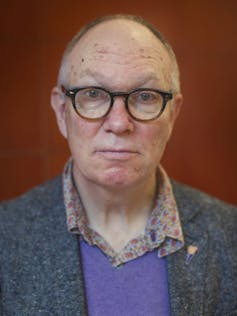

Who is a collaborator? What leads people to collaborate with the enemy in times of war? How do they justify their actions? These questions are at the core of an insightful comparative biography by the prolific, award-winning Dutch writer Ian Buruma.

Buruma has published numerous popular works of modern history, bridging the geographic divide between Asia and Europe. Such accounts have the potential to offer nuanced insights into global developments.

In his new book, The Collaborators: Three Stories of Deception and Survival in World War II, Buruma combines his interest in Asian history and culture with his Dutch background and upbringing, which was influenced by mythical stories about the heroic anti-German resistance during World War II.

The circumstances under occupation were, however, much more complex. Buruma asks his readers to focus on the unheroic opposite side, presenting the stories of three people accused of collaborating with the enemy. Instead of selecting clear-cut characters, he navigates the mysteries surrounding individuals whose lives are hard to interpret.

“Very few people, collaborators or resisters, can be reduced to single types,” Buruma observes. “Human beings, even malicious or craven ones, are too complicated for that.”

Review: The Collaborators: Three Stories of Deception and Survival in World War II – Ian Buruma (Atlantic)

Since World War II, the term “collaborator” has carried a negative connotation. It implies treason against one’s homeland, fellow citizens and community. Yet at every moment in history, the domination of one country over another has led some people to cross the line and cooperate with the enemy.

These individuals and groups have various motivations. Some are driven by their ideological affinity with the dominating power and the economic benefits of collaboration. Some believe in the perpetuity of the new regime. Some see collaboration as the only option to save their social position, or in some cases even their life.

If the decision to collaborate is followed by another regime change, such individuals face retribution, either in the form of judicial proceedings or mob justice, as often happened across Europe and Asia after the second world war. Judgements can be strict and, in many cases, lead the putative collaborators to the gallows or firing squad. Those who escape ultimate punishment suffer from social ostracism for the rest of their lives.

Is it even possible to be impartial when writing on this topic?

Conflicted personalities

In The Collaborators, Buruma examines three highly conflicted personalities. Some of them still polarise historians.

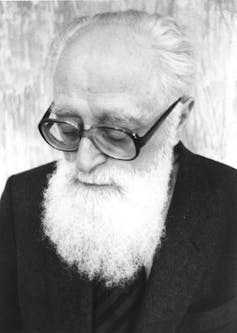

Felix Kersten, a Baltic German, was born in Estonia under Russian domination and became a prominent masseur in interwar Germany. He had several illustrious clients and eventually became the personal masseur of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler, along with several other high officials in Nazi-controlled Europe.

While Himmler and his SS companions were committing genocide against the Jews, Roma and Slavs across Europe, Kersten “made his life easier”, soothing his muscles, and relieving the “architect of the genocide” from the stomach cramps that troubled him.

Sven Appel/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

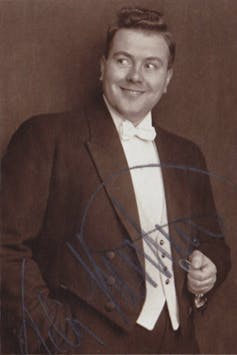

Buruma’s second sublect, Friedrich Weinreb, was born to Jewish parents in Lemberg (Lviv) in the Habsburg Empire, now part of Ukraine. He personally experienced the persecution of the Jews, first by Russian soldiers during World War I, and later by the genocidal Nazi regime.

Eager to survive at all costs, Weinreb “decided to play God”. He began to cooperate with the SS and Gestapo in the German occupied Netherlands, denouncing his fellow Jews and resistance fighters.

He pretended to have the ability to rescue Jews, collecting money from them and compiling seemingly protective lists for rescue trains that never left. Almost none of those who had trusted him, and paid him money, were rescued. There were also alleged cases of Weinreb sexually exploiting the women who had trusted him to protect them against deportation to the death camps.

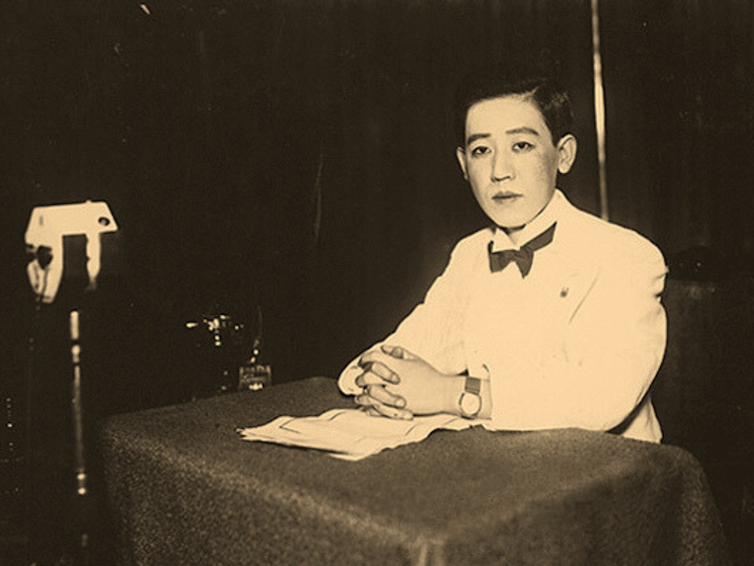

Buruma’s third subject, and the most mysterious, is Yoshiko Kawashima. As the daughter of a Manchu prince from the Qing dynasty, Yoshiko belonged to the Chinese imperial family, which was deposed from the throne in 1912. She lived in a shattered country, troubled by a civil war and dominated by the rising Japanese empire.

Yoshiko’s father gifted her to his friend, a Japanese nationalist who adopted her and later sexually abused her. Possibly as a consequence, she shaved her head and began wearing male clothes, including military uniforms.

After the Japanese invasion of China in 1931, Yoshiko worked for the Kwantung Army, spying for the Japanese. Addicted to drugs and living a bohemian lifestyle, she began to deteriorate physically and mentally. She participated in pro-Japanese propaganda, believing only the Japanese empire could help reinstate the Qing dynasty and get rid of Western influences in Asia.

Wikimedia Commons

Spying, sabotage, subversion, people-smuggling: the brave women who resisted the Nazis through non-violence

Not every reader will agree with Buruma pigeonholing such diverse characters as “collaborators”, when each has a completely different motivation for working with the enemy. The subtitle of Buruma’s book is “Three Stories of Deception and Survival in World War II”, but only one of his subjects, Weinreb, collaborated because he believed it was necessary to save his life.

Yoshiko – an ideological collaborator – believed the Japanese domination over China was in the interests of the Chinese imperial family and an Asian world weakened by infighting. But was she even a collaborator? As the adopted daughter of a Japanese chauvinist, her identity was at the border of Japanese and Chinese cultures.

The same question applies to Kersten as an ethnic German and an economic collaborator. He used his connections with top Nazis to lead an easy life at a time when most of Europe was suffering from the consequences of a major military conflict.

The inclusion of individual Jews, such as Weinreb, among collaborators with the Nazis has always been contentious. The term “collaboration” implies a possibility of choice. Can it be applied in a same way to those threatened with death because they belonged to a group slated for annihilation and to those who believed in the new order or hoped to maintain their social status?

Holocaust historiography has been struggling with this dilemma for decades. The scholar Lawrence Langer favours the term “choiceless choices”. But even this is problematic in the case of Jews who worked for the Germans with the sole intention of saving their own lives. In the case of Weintreb – a victim collaborator – the available evidence implies he decided to save himself and his family at the expense of others.

Holocaust remembrance: we must beware of well-intentioned mythmaking as events pass out of living memory

Historical corrective

Ilvy Njiokiktjien/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The lives of all three of Buruma’s subjects are veiled in mystery, thanks in part to the deceptions they helped to create. The memoirs and texts they left behind engage in self-exoneration and mythologising. Buruma does an excellent job of approaching their self-exculpatory tales critically and offering a balanced historical corrective.

The end of the war brought an incomplete closure to their stories. Weinreb, accused of collaboration with the Germans, was sentenced by a Dutch court to three and a half years in prison. He spent the rest of his life professing his innocence, with many still believing his side of the story.

Yoshiko was the only one to become a sort of celebrity during her lifetime. Fictitious stories about her actions supporting the Japanese in the conflict with the Chinese nationalists were published in the 1930s. She helped to spread the rumours.

Like thousands of other collaborators, she faced justice at the hands of the victorious powers. During the war, propaganda had created an aura around the cross-dressing former princess. Her notoriety as the Manchu princess turned Chinese Mata Hari and Joan of Arc may have contributed to her death sentence. She was executed in 1948 with one shot to the back of her head.

Only Kersten escaped almost unscathed. After the war, he tried to improve his reputation by spreading unconfirmed stories about people, and even whole communities, saved thanks to his interventions. He invented stories about persuading Himmler – with the help of his magic fingers – to abandon ideas about deporting the Dutch population and sending Finish Jews to the Majdanek concentration camp.

Public Domain

In the spring of 1945, Kersten certainly played a role in the facilitation of the last-minute negotiations between Himmler, the Swedish government, and the World Jewish Congress that led to the release of some prisoners from the concentration camps. But Buruma questions his motivations. He believes “Kersten was preparing for a world in which his job as Himmler’s private masseur was not the ideal credential for starting a new life”.

Weinreb, understandably, had his own strong motivations to present his wartime activities in a favourable light. But the tales he told after the war, in which he portrayed himself as a saviour who had skilfully played the Gestapo and allowed Jews to escape, are hard to believe. His actions led to the deaths of many Jews. Further accusations of fraud and sexual abuse during his postwar life tend to present him in a negative light. He has remained a polarising character.

Buruma concludes it is hard to pass a clear judgement on the “collaborators”. He is fascinated by their history, which he finds “surprisingly modern”:

their complicated backgrounds; their problems with national, sexual, and cultural identities; their resistance to and compliance with political forces that impose identities on people; and their deliberate blurring of truth and fiction.

One can side with Buruma’s cautious approach to such a complicated history. But I could not avoid the feeling that his assessment is too lenient, especially in Weinreb’s case.

The way Weinreb cheated desperate Jews, lulled them into false feelings of security, often for monetary gain; the way he sexually abused some of those who trusted him, and apparently continued to do so even after the war – these details can hardly outweigh any minor acts of assistance he may have performed. His collaboration was much more proactive than denunciations in moments of distress.

A split-second denunciation under duress, even if hardly commendable, could at least be comprehended in the situation he faced as a Jew under the Nazis. But even if he personally believed, or wanted to believe, he could outplay the SS, Weinreb went much further than that.