During the last global coral bleaching event in 2023 and 2024 , the Great Barrier Reef experienced the highest temperatures for centuries and widespread bleaching. With bleaching events becoming more frequent, the very existence of coral reefs is under threat.

This, in case it’s not clear, is a major problem. Coral reef ecosystems are essential for many species of plants and animals to survive. They provide humans with essential food security (many fish can’t survive without them), prosperity (via tourism and fisheries) and shoreline protection.

But heat stress can weaken corals, making them vulnerable to disease. At the same time, warm conditions can make the pathogens that cause disease stronger and more virulent.

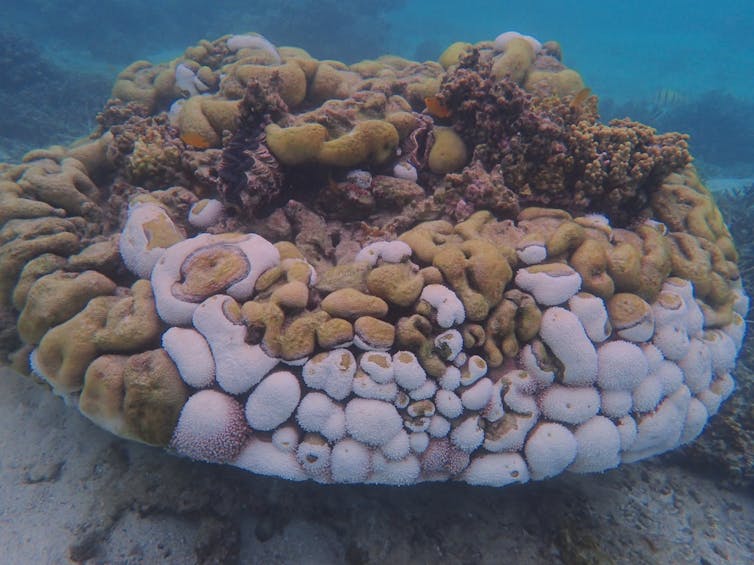

For our research, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, we tracked hundreds of coral colonies on One Tree Reef in the southern Great Barrier Reef in Australia during a 2024 heatwave. Weakened by heat stress, one particular type of boulder coral, Goniopora, developed a disease called black band disease.

These corals are old – probably at least 100 years old – and are like the old growth forest of the reef.

Six months later, 75% of these coral colonies in the reef community we monitored were dead.

This is especially worrying because these massive corals are normally quite resilient to heat stress. Even the strong are now struggling to survive.

And their huge, dead bodies can detach from the reef and hurtle around, crushing and destroying other corals in their path.

Photos taken by Alexander Waller

What we found on the Great Barrier Reef

We were originally tracking multiple sites on One Tree Reef in response to an extreme heatwave. We wanted to understand which coral species were more resistant and which were more sensitive to heat stress.

It was a surprise to see the bleached boulder corals quickly get infected by black band disease.

Black band disease is caused by a group of pathogenic microbes that kill coral tissue. These pathogens naturally occur in the environment but this is the first time such a disease epidemic has been observed on the Great Barrier Reef.

The disease appears as a black band, leaving behind bare skeleton as it destroys the coral tissue and spreads throughout the colony. Around the world, black band disease has been recorded on many different coral species. This disease has wiped out reefs in the Caribbean and fundamentally altered reef structure and function.

A review of coral diseases on the Great Barrier Reef shows that black band disease is mostly found on branching corals. Branching corals are more delicate and tree-like in comparison to sturdy, boulder corals.

Our findings are curious because on One Tree Reef only one particular species, a normally resilient boulder-like coral, was affected.

Black band disease virtually wiped out these corals at the site we were monitoring.

In other words, ordinarily strong and resilient corals are now succumbing to this disease. This is extremely troubling.

Photo taken by Alexander Waller

Why is this worrying?

This boulder-like coral, specifically from the genus Goniopora, has long, flower-like tentacles that sway with the currents.

Photo taken by Shawna Foo

A key reef-building coral on the Great Barrier Reef, it is very slow-growing compared to branching corals. Goniopora tends to be more resistant to disturbance and is often found in areas of lower water quality.

Living for hundreds of years, it can form extensively large coral patches supporting a wide range of organisms. These long-lived corals form the backbone structure of reefs providing refuge for a range of invertebrates and fish. Because of their size, they help buffer coastlines from waves.

We found that six months after the 2024 heatwave, the colonies we were tracking had been all but wiped out. At least 75% were dead.

Of the surviving colonies, 64% had experienced partial coral tissue death due to black band disease. While other species of corals showed signs of recovery after the heatwave, we didn’t see any recovery at all for the boulder corals.

Photo taken by Shawna Foo

Killer bowling balls

One Tree Reef is one of the most protected coral reefs on the Great Barrier Reef.

Previously, outbreaks of black band disease have been linked to coastal stressors such as pollution and high nutrients. Given One Tree Reef is 80 km offshore in open ocean, its isolation protects it from land-based pressures.

This makes the disease prevalence and rapid spread at One Tree Reef particularly concerning.

Once the coral tissue is killed by the disease, the skeleton is quickly covered by algae (and other organisms) that eat away at the skeleton. We noticed the breakdown of the boulder coral skeleton began surprisingly fast after the colony died.

This process usually takes many months to years. By six months, though, we found these boulder corals were unstable and began to detach from the reef.

This is dangerous as they can act like bowling balls if moved by waves and tropical cyclones, destroying surrounding reef.

These large structural corals that have survived for hundreds of years are now lost from this reef, resulting in a potentially permanent change to the ecosystem.

Black band disease is one of the earliest recorded coral diseases, first identified in the Caribbean. There, it has driven high mortality in corals and reshaped entire coral communities. Our results are beginning to echo these devastating disease outbreaks seen in the Caribbean.

With coral disease expected to rise with climate change, our findings reinforce the need for urgent global action and for ambitious climate and reduced emissions targets.