We’re a superstitious mob, but I don’t think it’s an exclusively Aboriginal reaction to instantly think Who’s died? when the phone unexpectedly rings late at night.

That night in 2008, my trepidation rose quickly when I heard it was my Uncle Gerry from Sydney who was on the line. But instead of sounding mournful, he sounded strangely … incredulous.

I’ve just been on the phone with a Bostock woman, a “white” Bostock woman from A.J.’s side of the family. You won’t believe what she told me about the white side of the family!

Immediately I knew he was referring to Augustus John Bostock, my non-Indigenous great-great-grandfather, whom Uncle Gerry had long ago nicknamed “AJ”. Uncle Gerry explained the elderly caller’s name was Thelma Birrell, but her family name, like ours, was Bostock.

He told me Thelma was an avid genealogist who had been researching the Bostock family tree for over 30 years. She told him she knew of her family’s rumour that her great-grandfather’s cousin, Augustus John Bostock, had taken up with an Aboriginal woman in the 1800s, but she didn’t know if there were any descendants from that union.

‘He was horrific!’: Nearly two thirds of family historians are distressed by what they find – should DNA kits come with warnings?

‘They were slave traders!’

Incredibly, after seeing Uncle Gerry’s photograph online, an obviously Aboriginal man with the Bostock family name, she somehow tracked him down. Uncle Gerry was a writer and film producer who participated in the political struggle surrounding the Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra and helped establish the Black Theatre in Sydney. In their long conversation, Thelma told him she had traced the Bostock family line back to the 1600s in England.

“Guess who our white ancestors were?” Chuckling to himself, Uncle deliberately paused for dramatic effect before he blurted out: “They were slave traders! A couple of generations of slave traders! Can you believe it? Imagine that!”

A deep, loud belly laugh erupted down the line, and he snorted as he added, “Those white ancestors of ours must be rolling in their graves knowing we turned out to be a mob of blackfellas!”

Up until that time, Augustus John Bostock was known to us only as “the whitefella who gave us our family name”, but on hearing this new information about his family history, a burning desire to find out more was suddenly ignited in me.

Author provided

Thelma had given Uncle Gerry her phone number, and I was surprised to find she lived only a little over an hour’s drive away from me on the Sunshine Coast. When I rang Thelma we chatted easily on the phone. And by the end of the call, she kindly invited me to come and visit her next time I was up that way.

Thelma was a lovely elderly lady who, years earlier with her husband Matthew, had travelled to England and to Australia’s southern states many times to collect her treasure trove of historical, archival and church records.

We spoke on the phone many times, and I enjoyed my face-to-face meetings with her over several cups of tea and delicious sweet treats. She was thrilled that I was interested in her work, and so proud to gift me a copy of her self-published book Merchants, Mariners … then Pioneers.

Thelma thoroughly enjoyed telling me all about the history of the non-Indigenous Bostock family prior to Augustus John’s birth.

She had been able to trace the Bostocks back to an ironmonger called Jonathan Bostock who lived in Chester in late 17th-century England. Jonathan Bostock was the father of Peter, Peter was the father of Robert, and Robert Snr was the father of Robert Jnr. The two “Roberts” were the slave traders.

Thelma explained that after slave trading was abolished, the British government arrested Robert Bostock Jnr and his business partner John McQueen, and sentenced them to “transportation” to the colony for 14 years.

She was quick to tell me that not long after they arrived here, “Governor Lachlan Macquarie pardoned them”. I had never heard of “pardons from the Governor” in Australian history, until Thelma showed me her transcription of the colonial secretary’s documents, in which the last sentence of the pardon declared:

By virtue of the power and authority Given and Granted unto me the Governor in Chief of the said Territory of New South Wales under such Warrant and conformally to the tenor thereof I do hereby order and direct that Robert Bostock therein named be forthwith discharged out of custody accordingly and he is hereby […] restored to all rights and privileges of a free subject. Signed, L. Macquarie, 1st January 1816.

Confused by the pardon, I remember asking Thelma for confirmation. “But Robert Bostock really was a slave trader, right?” She patted my hand and answered in a hushed voice, “Ooh yes, he was a very naughty boy.”

Silently, Thelma handed me the pretty floral matching teacup and saucer and busied herself pouring us more tea. Then once seated, she enthusiastically told me tales of Robert Bostock’s exploits after he arrived in Australia – about how he became an excellent merchant in Sydney, married a beautiful maiden, then moved to Van Diemen’s Land and expanded his business interests in Hobart, became a very wealthy landowner and lived in a grand mansion.

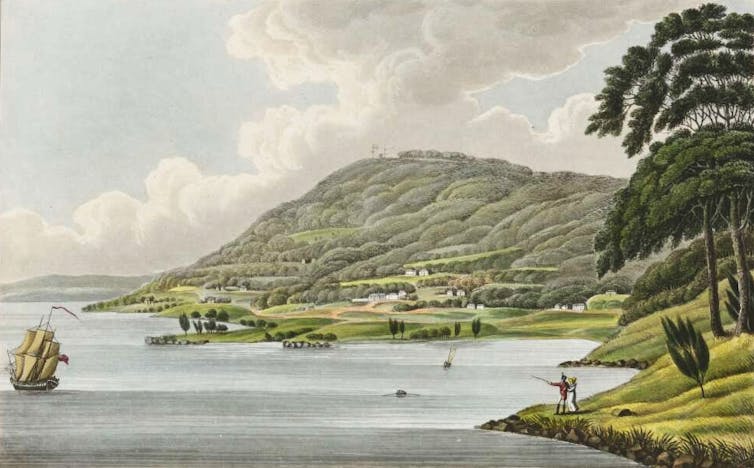

Wikimedia Commons

Most precious to Thelma were the stories about his children, who left Van Diemen’s Land and settled in southern Victoria. She was so proud of the white Bostocks’ narrative of dashing pioneers and nation-building settlers – but I wanted to pause the story and go back to understand more about the two “Roberts” who were slave traders.

I had so many questions, but her reluctance to discuss them was palpable.

In her book, she explained that even though Robert Snr had a number of ships and was successful to some degree, he was regarded as a small operator. Thelma wrote that “he exhorted his captains to treat the slaves well at all times” and she pointed out that “Robert [Snr] died 20 years before slave trading was actually abolished”, and that “trading in slaves continued up to the 1860s in different parts of the world”.

Befriending a slave-trade historian

Thelma’s writing moved on to present her outstanding genealogical research, and her proud narrative of the pioneering lives of the non-Indigenous Bostocks.

After the initial excitement of finding Uncle Gerry and connecting with me over cups of tea, Thelma and I continued to chat on the phone every now and then, but unfortunately a year or so later contact between us gradually faded away.

But before we lost touch, she introduced me to the slave-trade historian Emma Christopher.

Emma Christopher’s book includes the story of the Bostock slave traders

Emma’s field of expertise is the transatlantic slave trade, Pacific Islander labour, West African and historical slavery, and modern slavery. When a fellow historian told her that a mansion built by a convict transported for slave trading still existed in Tasmania, Emma was astonished. After years of extensive research, she had never heard of any slave traders in Australia.

Her response was like mine: she was gripped by the need to know more about the two Roberts. As the Australian expert on Bostock genealogies, Thelma was a major contributor to a website for Bostock descendants all over the world, and that is how Emma found her.

Being a spiritual person, I paid close attention to the intriguing way we all connected with each other. Seemingly out of the blue, Thelma found Uncle Gerry on the internet, then Uncle Gerry contacted me, and this led to my contact with Thelma. Emma was told about Robert Bostock, then found Thelma on the internet, and this led to her contact with me. My intuition was telling me this synchronicity was somehow orchestrated, that it was all part of God’s plan that I met Thelma and Emma.

Back then, I was focused on filling in the gaps in my family tree chart and finding out how Robert was related to my great-great-grandfather, Augustus John Bostock, whereas Emma, an established PhD historian and a published author, wanted to know all about the global legacy of the transatlantic slave trade.

Author provided (no reuse)

Despite our contrasting levels of academic knowledge at that time, our common interest in the history of the Bostocks quickly led to us becoming good friends. She helped me to see how interesting history can be when you push through the surface level and delve more deeply.

From the Caribbean to Queensland: re-examining Australia’s ‘blackbirding’ past and its roots in the global slave trade

‘I feel numb about it’

When Emma and I met, she was compiling research for a book about Robert Bostock Jnr and his business partner John McQueen, who were the only two convicted slave traders to have ever been transported to Australia. Emma was surprised when Thelma told her about the Aboriginal branches of the Bostock family.

Author provided

I say the plural “branches” because George Bostock, the cousin of my great-great-grandfather Augustus John Bostock, lived in the Northern Territory of Australia and had children with a Jingili woman, who, in the historical record, was only recorded as “unknown F/B” (“F/B” meaning “full-blood”; a child with traditional Aboriginal parents). So, it turned out that my family are not the only Indigenous descendants of Robert Bostock.

In 2018, Emma’s book Freedom in Black and White: A lost story of the illegal slave trade and its global legacy was published. It is a meticulous examination of the lives of the two Roberts, their tragic human merchandise and their captive African workers. As with Thelma’s book, I devoured every word.

The fates of the African captives who worked for Robert Bostock Jnr, and his Aboriginal descendants, are essential to Emma’s final discussion on the global legacy of the transatlantic slave trade.

Out of the blue, Emma said, “It must be a shock to be an Aboriginal Australian, a woman of colour, and find out that your ancestors were slave traders.” After what seemed like an excruciatingly long time, I realised I simply did not have the words to describe how I felt. Frowning, I lamely said, “I don’t know what to say … I feel numb about it – I just wish I had better words to say.”

That was over 12 years ago. After advancing my education, and undertaking intense study and archival research, it is only now that I am in the position to be able to present my research and provide answers to complex questions such as the one Emma posed.

Author provided

At the beginning of my research journey, I imagined my future book would be exclusively limited to my Aboriginal family history and would not include any of the non-Indigenous side of the family.

It was only when I was completing my PhD, and had read Emma’s extraordinary book, that I realised how integral my slave-trading ancestors are to the conclusion of this history of my multi-generational Aboriginal family.

‘Why didn’t we know?’ is no excuse. Non-Indigenous Australians must listen to the difficult historical truths told by First Nations people

Our ‘mob of blackfellas’

It is not known when Augustus John Bostock travelled north to Bundjalung Country, but at around 27 years of age he married my great-great-grandmother, an Aboriginal woman called One My.

I know this because on his death certificate, in the section marked “Marriages: Where, at what age and to whom deceased was married”, the corresponding details recorded were “Tweed River … about 27, One My otherwise Clara Wolumbin”. Her name, this record and other archival documents (which name her), as well as confirmation from Bundjalung Elders, indicate that she was a traditional Aboriginal woman from the Wollumbin/Mount Warning people.

Finding One My was incredibly exciting for me, because I actually had the name of one of the traditional Aboriginal ancestors from whom our “mob of blackfellas” is descended.

We always knew we were Bundjalung, and my father had frequently told us, “Our mob are from the Tweed”, but he didn’t know much else. Now I had a starting point.

This is an edited extract from Reaching Through Time by Shauna Bostock (Allen & Unwin, $34.99).