Westminster Abbey has announced that following the coronation of King Charles III and the Queen Consort, Camilla, in May 2023, the church’s famous Cosmati pavement will be opened up to the public. Every news story has been quick to highlight the unusual condition the abbey is imposing on visitors: given that this intricate mosaic was completed in 1268, people will have to remove their shoes to step on it.

Being able to see the floor as it was designed to be seen – underfoot and in motion – is an exciting experience. It goes beyond the visual and engages the senses more broadly. This will place visitors in a chain of tactile encounters that stretches back centuries. Many will relish the idea they are standing in the same spot as rulers past and present.

While the pavement has helped to stage events of national significance throughout its long history, its design and manufacture reflect international connections, especially with Rome. As I show in my 2022 book, Standing on Holy Ground in the Middle Ages, floor surfaces such as this took on considerable significance in the medieval period for the staging of ceremonies and to signal identity and connect people across time.

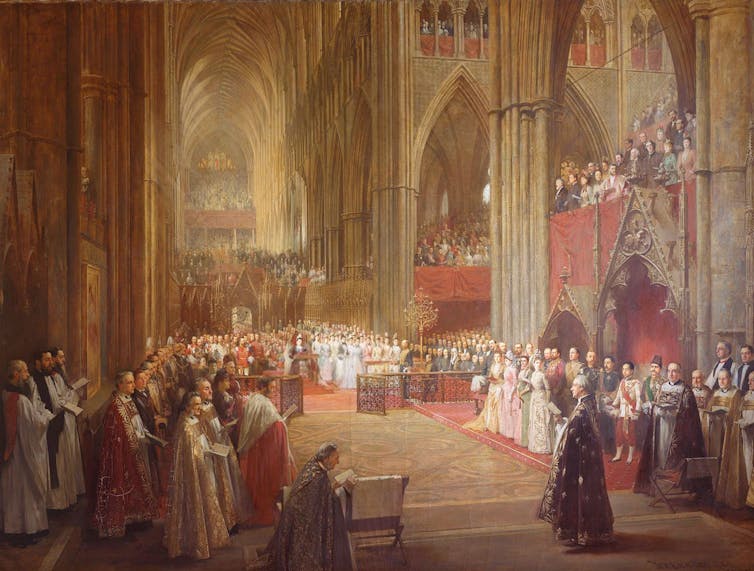

Public domain

Royal ceremonial

The Cosmati pavement lies in the sanctuary in front of the high altar. It has been part of the ceremonial life of the abbey since it was laid in the 13th century, during the reign of King Henry III.

Even then, coronations had long been held at Westminster and the mosaic was in place for that of Henry’s son, Edward I, in 1274. Physical contact with the pavement during the coronation ritual may have taken several forms. At one point, the king-to-be would lie on the ground in prayer, with precious textiles spread beneath him.

By the mid-19th century, the pavement was in poor condition and it was covered over with linoleum for protection. Extensive conservation work was undertaken between 2008 and 2010 to clean and repair it, before restoring it to its place in royal ritual and representation.

Christine Smith, CC BY-NC-SA

The Prince and Princess of Wales were married on the Cosmati floor in 2011. The portrait of Queen Elizabeth II by London-based Australian painter, Ralph Heimans, painted to mark her Diamond jubilee, depicts the late monarch standing on the mosaic, close to its central roundel of veined alabaster.

Westminster and Rome

The Westminster floor is the only one of its kind north of the Alps. It was created by marble workers from the Cosmati workshops in Rome, with stone of various colours imported from Italy and beyond. The design features a series of roundels set within interlaced circles and squares, which in turn encompass a variety of smaller-scale geometric patterns.

The function of the pavement also has a distinctly Roman dimension, referencing Old St Peter’s Basilica. The pavement of the original church on the site – replaced in the 16th century with the domed basilica – included several large roundels of porphyry.

Porphyry is a dark red stone with imperial associations. The roundels in the St Peter’s mosaic served as liturgical markers in the rituals for the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor. When Emperor Charles V was crowned not in Rome but Bologna, in 1530, roundels were marked out temporarily, by the master of ceremonies, on the floor of the Basilica of San Petronio.

The use and connotations of the pavement at Old St Peter’s will have been well known to both Henry III and Richard de Ware, the Abbot of Westminster, who visited Rome and has traditionally been credited with overseeing the laying of the mosaic in the abbey. Art historians Paul Binski and Claudia Bolgia have recently demonstrated the role played by the papal legate Ottobuono Fieschi in sourcing the marble and marble workers.

If the Westminster pavement’s design and use of porphyry expressed a powerful connection with Rome, its status reinforced that of the rulers who came into contact with it (and vice versa). Repeated use of the same spot also forged associations between rulers over time.

My research has shown that such creative use of the floors of important buildings was widespread during the Middle Ages. It often involved images as well as precious materials. And it served to connect members of communities as well as a succession of office holders.

Standing in socks

On a practical level, requiring visitors to Westminster to remove their shoes before walking on the pavement is about safeguarding the mosaics. Doing so is, of course, also a way of showing reverence, as visitors to sacred places the world over know. Medieval coronation rituals themselves often involved rulers going unshod as a sign of humility. A list of textiles purchased for the coronation of Edward III in 1327 includes cloth to be spread under the bare feet of the king as he walked, in a procession, to the abbey.

More fundamentally, though, being unshod makes for a much more vivid encounter with something this ancient. As a PhD student, I worked on the 12th-century floor mosaic of Novara cathedral in Piedmont, Italy. Here roundels depicting the symbols of the four evangelists were used by members of the clergy as markers for reading passages from the gospels during pre-baptismal ceremonies.

During my visit, several carpets had to be rolled up, so that I could see and photograph the floor. I was then allowed to step on to it in my socks – an enticingly thin layer between pavement and body, past and present.