Vikki Wakefield’s first foray into adult fiction begins with every parent’s worst-case scenario: single mum Abbie is at a busy outdoor market with her six-year-old, Sarah, when her daughter disappears. Sarah is suspected abducted, and despite all the police resources, there are no leads on her disappearance. Abbie is left to pick up the pieces of her life and carry on.

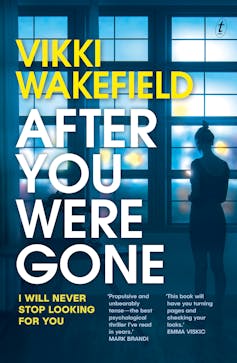

Review: After You Were Gone – Vikki Wakefield (Text Publishing)

Surviving the worst

In the very first chapter, we recognise this narrator as one who has survived the worst and lives with an absence of answers:

Not knowing was like living inside a well with slippery sides and the occasional crack between stones, a foothold, a scrabbling place.

Marketed as a psychological thriller, After You Were Gone is told from the first-person point of view of a mother who has struggled to survive her daughter’s disappearance, but who never fit the ideal mother mould.

Six years after her daughter’s suspected abduction, Abbie is starting a new life and marrying an older man – Murray – with children from a previous marriage. The day after her wedding, a mysterious caller promises the truth about what happened to her daughter if Abbie follows his very specific instructions. Having spent the past six years mired in guilt, blaming herself for Sarah going missing, Abbie goes along with the caller’s increasingly onerous demands.

Three time frames are interwoven throughout the novel: Before, Now, and After. Before is before Sarah disappeared. After is the years afterwards. Now unfolds in the present, with the mysterious caller. It is a clever structure because it gives us an understanding of what brought Abbie to this place, the level of stress she is under – and the reasons for the choices she has made, and is about to make.

Friday essay: why YA gothic fiction is booming – and girl monsters are on the rise

The bad mother

Wakefield creates nuanced and complex characters with different versions of the truth, and the tension between Abbie and her own mother is dialled high. In a conversation between Abbie and her sister Jess, we see the different ways siblings respond to the weight of maternal expectation:

“Why does she hate me so much?” I whispered to Jess.

“Because you pretend you don’t need her,” she said.

“You don’t need her.”

“But I pretend that I do.” Jess squeezed my hand.

The last taboo in society is the bad or indifferent mother – Wakefield is brilliant at showing us how insidious the cult of perfect motherhood might be for a young single mum who is hardly capable of looking after herself, much less a child.

Abbie’s pregnancy was accidental and Sarah’s father is not in the picture. Sarah is wilful and fiercely independent even at the age of six. “If I lost my temper, she would smile,” Abbie admits. “Some days I yearned to hand Sarah to a kind-faced stranger on the street and walk away.”

Abbie’s feelings about Sarah are both confronting, and familiar to anyone who has struggled with motherhood and the burdens of societal expectation. She suffers from maternal ambivalence: not an absence of love for one’s children, so much as an admission that motherhood is harder than expected, and a resentment of the burden of caregiving (and guilt at that resentment). Abbie recalls:

Around the age of two or three, Sarah progressed from simple needs to complex wants, and I cherished the hours when she was asleep while I was awake. From the moment she woke she was wired, swinging from manic activity to inconsolable tiredness, and the relentlessness of single parenthood made me hate myself on a daily basis.

Is it possible to describe the complexity and absurdity of motherhood?

Neat ending with unexpected twist

The self-loathing that Wakefield sets up enables the narrative to unravel in the now: after the phonecall, with Abbie becoming increasingly hostile to everyone around her.

It is believable until we reach the final scenes, where the ending does seem implausible in its neatness after so much chaos. Murray and Abbie’s relationship is only witnessed as it implodes, and this gives us scant insight into why they were together in the first place.

Without giving away the ending, part of what it hinges on is the premise that the narrator, Abbie, spent years throwing away her letters and packages:

my habit of throwing away mail, unopened, went as far back as when I’d lived in the unit with Cass, and only got worse after Sarah was taken.

Yet she keeps her surname when remarrying, in case her daughter might one day find her. It seems unlikely that someone whose child has been abducted throws away mail unopened – mail that could have actual leads, possible clues, or a letter of contact.

Despite this quibble, the twist was unexpected. Rereading, one can see the seeds sowed – tiny flecks here and there – which come to root the final story. After You Were Gone is more interesting for the way it portrays the complex pressures of motherhood than as a psychological thriller, but Wakefield succeeds in allowing the pressure of one to propel the other.