In November 1975, Truman Capote, the proudly gay author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood, unveiled the hotly anticipated second instalment of his unpublished novel, Answered Prayers. It was published in Esquire magazine.

To say it caused a scandal would be a gross understatement. Reputations were trashed and real harm caused. Capote ended his days a social pariah in his former New York society circles, incapacitated by a lifetime of prodigious substance abuse.

The unprecedented moral and social uproar that stemmed from the scandal has captured the attention of many writers, and is now the subject of the new anthology television series, Feud: Capote vs. The Swans.

The story to blame, La Côte Basque, 1965, takes its title from its setting: an achingly fashionable French restaurant in Manhattan. Industrial quantities of expensive champagne are consumed over lunch. All of a sudden, everyone in the room starts to stare and whisper:

Mrs. Kennedy and her sister had elicited not a murmur, nor had the entrances of Lauren Bacall and Katharine Cornell and Clare Booth Luce. However, Mrs. Hopkins was une autre chose: a sensation to unsettle the suavest Côte Basque client.

As her all-black attire suggests (“black hat with a veil trim, a black Mainbocher suit, black crocodile purse, crocodile shoes”), Mrs. Hopkins is in mourning. This doesn’t go unnoticed:

“Only,” said Lady Ina, “Ann Hopkins would think of that. To advertise your search for spiritual ‘advice’ in the most public possible manner. Once a tramp, always a tramp.”

What, the reader wonders, has Ann Hopkins done to deserve such an admonishment? Lady Ina Coolbirth leaves us in no doubt whatsoever. Ann Hopkins is simply not to be trusted. If Ina is to be believed, we are dealing with someone who once quite literally got away with murder:

But it could have been an accident. If one goes by the papers. As I remember, they’d just come home from a dinner party in Watch Hill and gone to bed in separate rooms. Weren’t there supposed to have been a recent series of burglaries thereabouts? – and she kept a shotgun by her bed, and suddenly in the dark her bedroom door opened and she grabbed the shotgun and shot at what she thought was a prowler. Only it was her husband. David Hopkins. With a hole through his head.

This is a true story. The only difference? Capote changed the names.

The real-life ‘Mrs. Bang-Bang’

Ann Hopkins is a fictional cutout for the socialite Ann Woodward, born Angeline Lucille Crowell on a farm in Kansas in 1915. In 1943, she married one of America’s richest men, William Woodward Jr.

On 30 October 1955, the Woodwards, whose marriage was violent and fractious, were guests at a dinner party held in the honour of Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, in Oyster Bay, New York. There was talk of the spate of burglaries that had recently occurred in the area. Ann, who suffered from insecurity and social anxiety, drank more than usual.

Returning home with her husband, she washed down some sleeping pills and went to bed, not long after midnight. At two in the morning, Ann was woken by the sound of her dog growling. Thinking there an intruder in the house, Ann grabbed the shotgun she kept by her bedside. She moved out into the hallway, where she saw the silhouette of a man. She opened fire without issuing a warning. The body crashed to the floor.

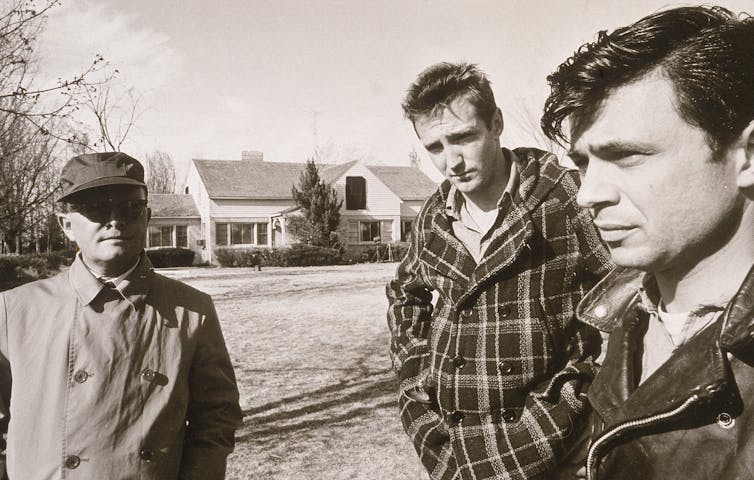

Bettman/Getty Images

Or rather, as the researcher Roseanne Montillo notes, “that is the story she would tell the police, her mother-in-law, and all who asked during the rest of her life. Many would doubt her, including Truman Capote.”

Capote crossed paths with Ann Woodward in the Alpine town of Saint Moritz in the autumn of 1956. Ann did not take kindly to having her meal interrupted. She dismissed Capote with a homophobic slur.

He returned fire, calling her “Mrs. Bang Bang”. The sobriquet stuck to Ann for the remainder of her life. Montillo adds that Capote “would repeat the story of how he had met the notorious Ann Woodward whenever the opportunity presented itself, embellishing his tale and relishing each detail”.

The Clearing’s investigation of The Family invites us to ask: what’s the appeal – and risk – of crime stories based on real events?

‘What I’m writing is true’

While they would have been loath to admit it, Truman Capote and Ann Woodward were similar in certain ways.

Both overcame childhood hardship and adversity. And much like Ann, the precocious Capote, who was born Truman Streckfus Persons in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1924, craved success, stardom and access to the trappings of elite society from a very early age.

Regardless of whether he truly appreciated this, it seems fair to say Capote’s encounter with Ann Woodward made quite the impression on him.

Capote’s authorised biographer, Gerald Clarke, reveals Ann Woodward was on the author’s mind when he came up with the initial idea for Answered Prayers in 1958. Clarke describes how Capote originally “planned to make Ann his central character; in a list of eight names he jotted down in his journal, hers was the only one he had underlined”.

Capote’s conception of Answered Prayers, which he struggled with and talked about for decades, developed over time. Marcel Proust loomed large in Capote’s imagination. In his monumental novel-cycle Remembrance of Things Past, Proust scrutinised the social machinations of the Parisian upper classes at the turn of the 20th century.

Capote conceived of his project – which took shape as a roman à clef – in equivalent terms. Clarke quotes Capote as saying:

I am not Proust. I am not as intelligent or as educated as he was. I am not as sensitive in various ways. But my eye is every bit as good as his. Every bit! I see everything! I don’t miss nothin’! What I’m writing is true, it’s real and it’s done in the very best prose style that I think any American writer could possibly achieve. […] If Proust were an American living now in New York, this is what he would be doing.

Capote clearly wasn’t lacking confidence. Answered Prayers was going to depict “American society in the second half of the twentieth century. This book is about is about you, it’s about me, it’s about them, it’s about everyone.”

Capote was to tell the story of American society via thinly fictionalised versions of some of the wealthiest and most fashionable women in the world. As journalist Laurence Leamer tells it,

everyone knew these characters were based on his closest friends, the coterie of gorgeous, witty, and fabulously rich women he called his “swans”.

Capote coined the term in an essay written for Harper’s Bazaar in October 1959. He claimed that

as is generally conceded, a beautiful girl of twelve or twenty, while she may merit attention, does not deserve admiration. Reserve that laurel for decades hence when, if she has kept buoyant the weight of her gifts, been faithful to the vows a swan must, she will have earned an audience all-kneeling; for her achievement represents discipline, has required the patience of a hippopotamus, the objectivity of a physician combined with the involvement of an artist, one whose sole creation is her perishable self.

There is a lot to unpack in this passage. Capote is essentially suggesting there is more to beauty than youth and looks alone. He considered style and self-presentation to be infinitely more important when it came to determining whether a beautiful women might be elevated to the position of a swan.

Leamer holds that there were probably only “a dozen women who Truman could have deemed true swans. They were all on the International Best-Dressed Lists, they were each celebrated in the fashion press and beyond, and they all knew one another.”

Santi Vasalli/Getty Images

Babe Paley (wife of CBS chairman William S. Paley). Slim Keith, ex-wife of director Howard Hawks and producer Leland Hayward (and the model for Lady Coolbirth). C.Z. Guest, a renowned beauty painted by Diego Rivera and Salvador Dalí. And Lee Radziwill, deemed, in La Côte Basque, 1965, so superior to her sister Jackie Kennedy, she was “not on the same planet” (the sisters are also described as “a pair of Western geisha girls”).

This is a partial list of the world-famous women who counted Capote as their close friend throughout the 1960s and 70s. He dined with them, holidayed with them, and spent countless hours talking with them.

Having earned their trust, the swans told Capote everything. This gave the writer, an outsider and perceived social inferior, unrivalled access to the upper echelons of American aristocracy.

Capote spent years getting to know and understand these women. In Leamer’s retelling, Capote

appreciated the challenges of their star-crossed lives, what they faced, and how they survived. He had everything he needed to write about them with depth and nuance, exploring both the good and the bad, the light and the darkness. Answered Prayers would be his masterpiece, he knew – the book that would give him a place in the literary pantheon alongside the greatest writers of all time.

Capote seems to have genuinely believed this. But things did not go according to plan.

Binge

Masturbation, misogyny, murder

In retrospect, it is clear that the odds were stacked against Capote from the very beginning.

At the start of January 1966, Capote signed a contract with Random House for a novel titled Answered Prayers. The advance was an eye-watering US$25,000 (equivalent to approximately US$240,000 today).

However, by the time he actually sat down to write the book, he was already under a great deal of pressure. Part of the problem had to do with his “real-life novel” In Cold Blood, which appeared in print just two weeks after he signed the paperwork for Answered Prayers.

In Cold Blood is a creative recounting of the brutal Clutter family murders of 15 November 1959, which took place in the small farming community of Holcomb, Kansas. It was a massive hit with American readers, selling over 300,000 copies in 1966 alone.

The book made Capote the most famous writer in America. Everyone now wanted a piece of him. He was interviewed in countless magazines and appeared on numerous television talk shows. An indefatigable self-promoter, he talked up Answered Prayers whenever he possibly could.

In Cold Blood, which took six years to research and write, left Capote physically, mentally and creatively exhausted. He struggled to maintain focus and missed multiple deadlines. Answered Prayers kept getting pushed back. People started to wonder if it would ever see the light of day.

Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Things came to a head in 1975. Under pressure to deliver the goods, Capote, who had until this point been incredibly secretive about the contents of his book, agreed, against the advice of his editor, to publish four chapters of Answered Prayers in Esquire.

The first excerpt – Mojave – appeared in June, but garnered little attention from readers and critics. In contrast, the October publication of the scabrous, sexually explicit La Cote Basque, 1965 shocked the literati and set the tongues of socialites wagging.

Capote had spent years tantalising friends and readers with the promise of an epoch-defining, Proustian masterpiece, only to deliver something else entirely.

Masturbation, menstruation, misogyny, murder. Adultery, gossip and gallons of alcohol. Readers who thought they were getting a finely wrought piece of social critique were left scratching their heads in bemusement. What on earth could have possessed Capote? What was he hoping to achieve by besmirching the reputations of those closest to him?

In Killers of the Flower Moon, true crime reveals the paradoxes of the past

Was the book any good?

With the benefit of hindsight, I think the overwhelming majority missed the memo when it came to Answered Prayers.

To be sure, the work is infinitely more explicit and graphic (in terms of tone and subject matter) than many, if not all of Capote’s earlier literary ventures. By the same token, it is clear Answered Prayers responds to (and even builds on) advances made in his earlier work.

Take, for instance, In Cold Blood: Capote’s conceptual breakthrough came when he realised “objective” forms of journalistic inquiry could be brought into productive dialogue with practices more closely associated with creative writing.

My hunch is he thought he could pull off an equivalent trick with Answered Prayers. Only this time, he uses gossip.

As the art historian Gavin Butt reminds us, gossiping is a serious business. Gossip can serve a positive, even joyous function: it is a “social activity which produces and maintains the filiations” of community.

To put this another way: if used in a strategic and appropriate fashion, gossip can bring people together. It can help to build and sustain social groupings predicated on the basis of shared knowledge (of sexual matters).

But when it came to Answered Prayers, Capote took things a step too far. Pretty much all we get is a constant stream of gossip. Characterisation, for one thing, goes entirely out of the window. So does plot. We see this, of course, in La Cote Basque, 1965. But the same is true of the other available sections of the novel.

Consider Unspoiled Monsters, the first chapter in the posthumously published book. Our narrator, P.B. Jones, is an aspiring writer and bisexual gigolo. (His clients include an acclaimed American playwright who is a thinly veiled Tennessee Williams: “a chunky, paunchy boose-puffed runt with a play mustache glued above laconic lips”.)

This is how Capote introduces his narrator to the reader (note, here, the emphasis on journalistic reportage):

“My name is P. B. Jones, and I’m of two minds whether to tell you something about myself right now, or wait and weave the information into the text of the tale. I could just as well tell you nothing, or very little, for I consider myself a reporter in this matter, not a participant, at least not an important one. But maybe it’s easier to start to start with me.

Having offered his greetings, Jones, whose hardscrabble biography reads very much like his creator’s, starts gossiping and name-dropping indiscriminately. He never lets up. Certain of the swans crop up from time to time, as does Capote’s literary touchstone:

Think of Proust. Would Remembrance have the ring that it does if he had made it historically literal, if he hadn’t transposed sexes, altered events and identities? If he had been absolutely factual, it would have been less believable but […] it might have been better.

To which the reader of Answered Prayers might simply reply: touché.

Binge

Settling scores

Be that as it may, Gerald Clarke is surely right to suggest Capote had “more than literature on his mind” when he agreed to publish parts of Answered Prayers. In part, he was looking to settle scores. Answered Prayers represented an opportunity “to get back at some of his rich friends who, for one reason or another, had offended him over the years.”

The psychologist William Todd Schultz concurs. He reasons that with La Côte Basque, 1965 in particular, Capote “bit down hard on the smooth, socialite hands that fed him.”

Capote’s decision to do so came with some unintended, yet disastrous consequences. Having gotten hold of an advance copy of La Cote Basque, 1965, Ann Woodward, who had a long history of depression, overdosed on barbiturates and passed away. She was a few months shy of her 60th birthday.

Schultz makes the point that Ann Woodward’s reaction to Capote’s story “was the first, by far the saddest and most anguished, but hardly the last”. Capote’s swans, having recognised their fictional selves, recoiled in horror and disgust. They immediately cut Capote out of their lives.

Try as he might, Capote, who claimed his intentions had been misunderstood, couldn’t win the swans back over. Many of them never spoke to him again.

Capote never recovered. And he never came close to finishing Answered Prayers. Dulled by a poisonous cocktail of drink and drugs, his literary skills deserted him long before he died on 25 August 1984.

As chance, or maybe fate would have it, he died at exactly the same age as Ann Woodward. From start to tragic finish, it really does seem as if the lives of these two ambitious social outsiders ran along parallel lines. Given how much they despised each other, I can’t help but wonder what Capote and Woodward would have made of such dismal symmetries.