I am one of 400 descendants of a Baloch-Afghan cameleer man, Goolam Badoola, and an Aboriginal Badimiya Yamitji woman, Mariam Martin.

As I share these stories told to me by my Elders, I pray they are used as a means for others to recognise the resilience in these historical lessons as a vessel for good action. As humans, we should be naturally inclined towards performing good acts in service of humanity.

In Islam, this concept is called fitrah, the natural predisposition to incline towards right action and submission to the Creator. In our faith, we are also taught that deeds are rewarded by their intentions and sincerity.

As I write this piece, I do so with the sincere intention that my words penetrate living hearts and provide a means of coming together to serve humanity in good action.

To me, as a fourth-generation descendent of an Afghan Baloch cameleer, the Uluru Statement represents an opportunity to come together and walk hand in hand as we build this country, with the same spirit as my great-grandfather.

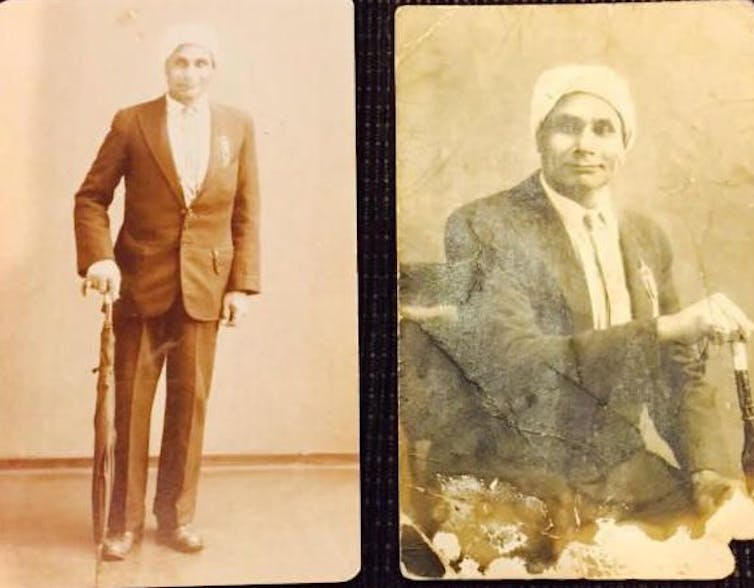

Author provided

Goolam, a Muslim cameleer in Australia

Goolam was born in 1872 in British Balochistan, India. He was from a Baloch background, an ethnic group located on the Iranian plateau. From the age of six, he grew up looking after camels. During his teens, he would travel more than 22 kilometres each day with his camels to sell wood at Karachi Port, British India.

During the colonial exploration of Australia, camels and camel drivers were shipped to work on the arid land to cart goods for transportation. Goolam was determined to join this line of work and travel to Australia with his camels.

In December 1890, Goolam walked more than 40km from Gaddap to Karachi Port with his camels, only to be stopped at the gate by a tall Indian Sikh man with a turban. He was advised that the ship had met its quota and no one else was allowed to board.

As Goolam walked away, upset and disappointed, he noticed an agitated loose male camel that others were unable to subdue. He recognised the camel’s temperament as being caused by the winter mating season and decided to intervene before the situation escalated. He hurled a rope around the camel’s neck, dropped it to the ground and pinned the camel between the nostrils to bring him to a halt.

The captain of the ship witnessed this and without hesitation cried out, “I want that kid on this ship.” In our Muslim tradition, we call this naseeb or qadr, which loosely translates to “destiny”. Although he didn’t speak the language, it was Goolam’s naseeb to board that ship, travelling over three months to unknown lands. What was to come, nobody could have known.

Goolam arrived in Port Augusta, South Australia, as an energetic adolescent. He worked as a camel driver for a telegraph company called Elders, delivering goods for them for the next ten years. A gold rush in 1900 then prompted Goolam to move to Western Australia and work for a company called T & J Camel Carting Company in the Murchison region, transporting water to the miners from local waterholes.

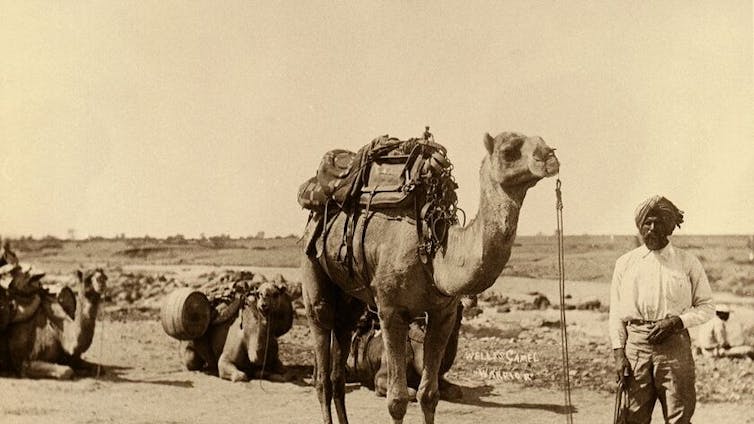

Australia’s Muslim Cameleers, Wakefield Press/State Library of South Australia

During that time, there was a catastrophic cyclone, and flooding blocked roads in the isolated towns of the Murchison region. Goolam used his camel trains to bring people to safety. He also transported water and rations to flood victims.

The WA government of the time recognised this extraordinary effort by rewarding him with citizenship rights and monetary remuneration. He used this money to purchase a property in Mount Magnet, named Bulgabardoo Station. Goolam established a company in the cattle industry and became one of the most successful pastoralists in WA.

My great-grandfather worked tirelessly for this nation, in a racist climate where the White Australia policy created division between white Australians and people of colour.

A letter of recommendation by the Pastoralists’ Association of WA, written in 1922, remarks that “suffice to state that Goolam Badoola […] despite his colour, has served Australia well”.

Although Goolam contributed to this country for more than 40 years, he was still seen as inferior due to the colour of his skin. He was a man who served the community and always helped those in need, despite being disadvantaged due to his race and background. Goolam recalls this environment of racism in an article published in 1922, when he encountered racist abuse by a white man in Geraldton.

Long history with Islam gives Indigenous Australians pride

Goolam’s story, in his words

He writes:

It is eleven years since I last came to Geraldton. I was born in Karachi, India [Balochistan] and under the British flag. As far as I know England has been the ruler of my country for over 200 years, and my benefit goes to England just the same. I was walking along a Geraldton street, when a gentleman who was smoking a cigar came up past me and said, “Good-day, White Australia,” and I answered “Good gentleman. Won’t you allow me to walk along your street if it’s man to man, I did more work in Australia, than what you did.”

So I am going to advertise what work I did in Australia, so that you can see it in the paper. I am a poor Indian man, and I won’t have any quarrel with anyone. In 1890 I was employed by Faize and Tagh Mahomet, who were the first men to bring camels over to Australia. In 1891 I landed in South Australia; in 1893 I arrived in Western Australia; in 1893 I saved 70 diggers at Siberian Soak; one man died, and the rest I saved.

These diggers depend on the Siberian Soak, which gave in and there was no more water. These diggers sent in a report to the Government for help, and the Gov- ernment hired 40 camels from Messrs Faize and Tagh Mahomet. I was the man who did the work. I got an order from the boss to go to all the houses and save the people. Myself and three other employees went, and I was in charge of the team.

From Coolgardie to Rasar Soak is 30 miles through a rough track. From Rasar Soak to Siberian Rush is 42 miles. There was hardly any road. I pushed through 72 miles without stopping, and I saved 70 men, and one died before I got there. There was poor me who did that work. I was new to the country, and couldn’t speak the language, and got no thanks for what I did. I suppose my boss got the benefit.

In 1896 I was employed by the Octagen Mining Company in Menzies, 8 miles from Menzies west. I used to cart water for the miners from the condenser, 300 gallons every day, for these people. One hundred and eighty were working. One morning I went down to the condenser; the man told me that the condenser was broken. I turned back and went 8 miles home and I told my boss that the condenser was broken, and he said to me, “My God, Badoola, all these people will die for want of water. Next water will be 30 miles from Menzies to get. It’s too late now. Will you go early in the morning 30 miles to get it?” I said “All right, boss. You give me a letter to that boss who owns the condenser and I will get the water.”

He gave me a letter at four o’clock in the afternoon and I started straightaway, and I never told the boss. I pulled through with 10 camels with water casks all right on a very small pad. I did a special trip for the water and all that afternoon, and all night and next morning early I brought the water and supplied all these miners before the boss got out of his bed.

I just unloaded the last camel, when he came out of the door and said, “Hurry up, Badoola! Go and bring the water.” He said: “After you left at 5 o’clock more than 25 people gave notice to leave, because they were dying for want water.” I said to the boss, “I will bring water tonight.” He said, “You will be a good boy if you bring water tonight.” He thought I was just starting and bring the water.

I could not speak well enough English to make him understand that I brought the water last night. I told him I had been working ever since yesterday morning at 7 o’clock, and got him by hand and took him to the drums and told him to look, this one full, that one full, and all full. “Oh!” he said. “You been there since yesterday, 4 o’clock you did good work – saved 108 men from perishing for water, and now,” he said, “I give you £5 present and £2 rise in wages.”

In 1900 I was a camel owner and carrier from Cue to Lake Way. There was a big flood in 1900, and I saved women and children from starvation. All the country was flooded. I loaded 150 camels and 40 pack horses with food. They were all trying to get through the tucker to Lake Way, but they could not get through, on account of water and bog. I took my eight camels, loaded up with flour, seven miles through water and saved the women and children from starvation at Lake Way.

In 1911 I started sheep-breeding and squatting. I bought land from six different men with no wells or no improvements on the land – just all bushes I battled along and worked hard, built in Australia, yet in that little time. Last year, in May, I was offered £26,000 and yet that gentlemen who won’t allow me to walk the street and said, “Good-day, White Australia.”

My declaration shows I did more good for Australia than the man who was smoking the cigar and said, “Good-day, White Australia.” I think he want me to do his work yet.

It’s 20 years [since] they stopped the Indian man from coming to Australia, and it’s 20 years [ago] I remember plenty of my countrymen in India working the camels carting the stuff at small rates back in Goldfields, and giving a chance to the miners to find plenty of gold. They could not do it today.

Also that they carted the stuff out for squatters at a cheap rate, and gave a chance to the squatters to grow, and they called it cheap labour, and stopped them coming to Australia.

They did not know they had a good slave to work for them. Whoever the gentleman was who said “Good-day, White Australia” has enough in this paper to read. I did not [do] any harm to him.

Australian politics explainer: the White Australia policy

Brotherly friendships among camel drivers

As a proud descendent of Goolam Badoola, I reflect on his story as it takes me on an emotional journey. I try to envision what it must have been like for my great-grandfather who migrated in the late 19th century as a Baloch camel driver, working tirelessly to build this country.

Goolam worked a hard life alongside other disadvantaged people of colour, ethnic blends of cultures existing simultaneously as they worked through the harsh, arid golden outback.

I reflect on the brotherly friendships that were formed between the camel drivers from Afghan, Pashto, Baloch and Sikh backgrounds. And I think about my own great-grandfather’s personal bonds with his fellow camel-driver companions whom he named his sons after – Numroze (my grandfather), Meerdost and Noordin – sons whom Goolam raised with his wife, Mariam Martin.

Australia’s Muslim Cameleers, Wakefield Press/State Library of South Australia

In 1915, Goolam employed a Malay man by the name of Mohammad Kassem, whose name was changed by the British to Michael (Mick) Martin, to work on Bulgabardoo Station. Mick was married to Lizzy Little, a Badimiya Yamitji woman and they had three children – Fred, Ned and Mariam Martin.

My great-grandparents’ ‘illegal’ marriage

Mick, being Muslim, wanted his daughter to marry a Muslim man and had asked Goolam if he would honour his daughter by marrying her. Goolam was in his mid-forties and Mariam was 17 years of age. The marriage took place in 1917 at Perth Mosque on William Street with a traditional Muslim ceremony.

The marriage was not recognised by the state. Mariam was a half-caste Aboriginal according to WA law, and as such she was subject to section 42 of the Aborigines Act 1905, which stated: “No marriage of a female aboriginal with any person other than an aboriginal shall be celebrated without the permission, in writing, of the Chief Protector.”

The Chief Protector at the time, A.O. Neville, served a notice to the newlyweds stating the illegality of their marriage, and instructing that Mariam be relocated to a mission settlement to work as a domestic servant. Goolam and Mariam fought for their marriage in court in Cue.

Mariam wrote a letter to the Warden with her pleas:

Dear Sir, I’m writing you a few lines and I hope you will take a great interest in it because I’m a poor unfortunate girl, and the Aboriginal department is trying to put me away from my good home.

Eventually, their marriage was approved, and Mariam was permitted to remain with her husband. They had four children together.

The injustice reared its head again when A.O. Neville demanded that Goolam and Mariam give up their children to be sent to mission settlements.

According to section 8 of the Aborigines Act 1905, “The Chief Protector shall be the legal guardian of every aboriginal and half-caste child until such child attains the age of sixteen years.”

Author provided (no reuse)

Over the years, the state authorities paid visits to the station to take the children away; however, Mariam hid the children in boxes or underground within the 200,000 acres of their property. Despite Goolam having a good reputation among other white pastoralists, and being known as a “good man”, his family life was still disturbed by these unjust policies.

In 1929, Mariam passed away at the age of 29 and Goolam was left to look after their four children. He feared the children would be taken away and stripped of their Aboriginal Muslim identity. Goolam made plans with his nephew Ibrahim, who worked on his station, to accompany his children and transport them back to Balochistan, a safer environment free from persecution.

On July 6 1931, they boarded the Narkunda and sailed away from Australia. In their possession were Certificates Exempting from the Dictation Test, which at the time were issued under the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 for non-white residents to travel overseas and return to Australia. Goolam stayed in Australia to sell some of his properties and departed a year later.

In the decades that followed, Goolam was granted approval for extension applications for himself and his children to return to Australia. In an application dated December 13 1947, Goolam said,

You know my sons were born in Western Australia and as such they are the natural Nationals of Australia. This is also an urgent matter involving as it does the future of myself and my children.

This statement demonstrates that Goolam was a fighter who never gave up advocating for the rights of his children and for future generations to return to their native land when it was safe for them to do so.

Author provided

The story of Goolam and Mariam, as recounted by my family, shows the determination they had in fighting against all odds to remain married and raise their children in the manner they wanted. Goolam fought against the 1905 policies and advocated for his marriage in court.

He took extreme measures in protecting the Muslim and Aboriginal identities of his children by shipping them away to Balochistan. Goolam also advocated against the status quo and the White Australia policy by establishing a successful business as a pastoralist.

Hidden women of history: Kudnarto, the Kaurna woman who made South Australian legal history

Policies shape lives and generations

I believe this strength and resilience has been passed down to Goolam and Mariam’s descendants, as we fight for our right to remain on this land as Aboriginal Muslims.

In the same way, we fight for causes such as the Uluru Statement from the Heart. It is evident that policies and legislation shape lives and generations. My family’s story is one of many that have been dictated by the laws and policies created by the white man.

Australia should take heed of these stories and realise the importance of enabling First Nations people to make decisions for themselves and not go through what my family experienced. These stories demonstrate why Indigenous peoples need a constitutionally guaranteed First Nations Voice, so we can have a fairer say in laws and policies made about us. Such a measure might have prevented, or at least improved, some of the unjust policies of the past.

The Uluru Statement is an opportunity to bring communities together for generations to come. Just as Goolam Badoola served his community with good intentions and sincerity, we must also revisit our intentions and instil the sincerity in this good action, to enable the empowerment of First Nations people.

This is an edited extract from Statements from the Soul: The Moral Case for the Uluru Statement from the Heart, edited by Shireen Morris and Damian Freeman (Black Inc.).