At the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s Special Collections, where I am head curator, we’ve recently completed a major digitization and rehousing project of our collection of over 5,400 photographs made by Lewis Wickes Hine in the early 20th century.

Traveling the country with his camera, Hine captured the often oppressive working conditions of thousands of children – some as young as 3 years old.

As I’ve worked with this collection over the past two years, the social and political implications of Hine’s photographs have been very much on my mind. The patina of these black-and-white photographs suggests a bygone era – an embarrassing past that many Americans might imagine they’ve left behind.

But with numerous reports of child labor violations, many involving immigrants, occurring in the U.S., along with an uptick in state legislation rolling back the legal working age, it’s clear that Hine’s work is as relevant today as it was a century ago.

‘An investigator with a camera’

A sociologist by training, Hine began making photographs in 1903 while working as a teacher at the progressive Ethical Culture School in New York City.

Between 1903 and 1908, he and his students photographed migrants at Ellis Island. Hine believed that the future of the U.S. rested in its identity as an immigrant nation – a position that contrasted with escalating xenophobic fears.

Based on this work, the National Child Labor Committee, which advocated for child labor laws, hired Hine to document the living and working conditions of American children.

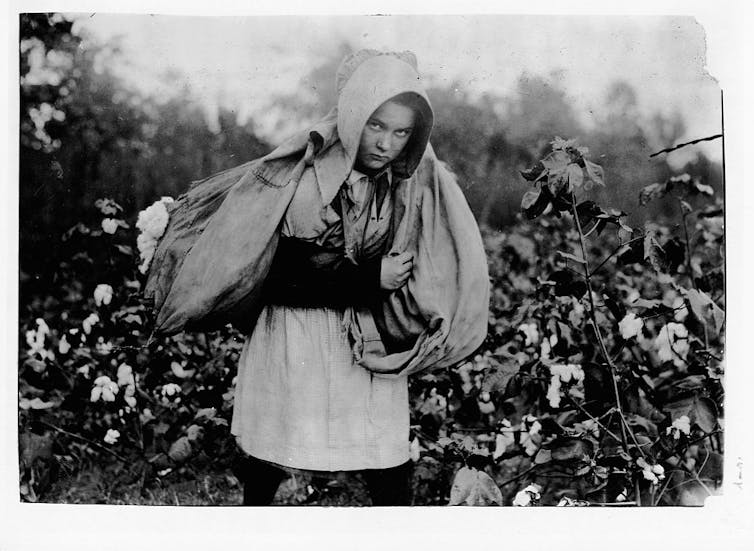

Gelatin silver print. 5 x 7 in. The Photography Collections, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (P148), CC BY-SA

By the late 19th century, several states had passed laws limiting the age of child laborers and establishing maximum working hours. But at the turn of the century, the number of working kids soared – between 1890 and 1910, 18% of children ages 10 to 15 were employed.

In his work for the National Child Labor Committee, Hine journeyed to farms and mills in the industrializing South and the streets and factories of the Northeast. He used a Graflex camera with 5-by-7-inch glass plate negatives and employed flash powder for nighttime and interior shots, hauling upward of 50 pounds of equipment on his slight frame.

To gain entry into factories and other facilities, Hine sometimes disguised himself as a Bible, postcard or insurance salesman. Other times he’d wait outside to catch workers arriving for or departing from their shifts.

Along with photographic records, Hine collected his subjects’ personal stories, including their ages and ethnicities. He documented their working lives, such as their typical hours and any injuries or ailments they incurred as a result of their labor.

Hine, who considered himself “an investigator with a camera,” used this information to create what he termed “photo stories” – combinations of images and text that could be used on posters, in public lectures and in published reports to help the organization advance its mission.

National Child Labor Committee collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Legislation follows

Hine’s muckraking photographs exemplify the genre of documentary photography, which relies upon the perceived truthfulness of photography to make a case for social change.

The camera serves as an eyewitness to a societal ill, a problem that needs a solution. Hine portrayed his subjects in a direct manner, typically frontally and looking straight into the camera, against the backdrop of the very factories, farmland or cities where they worked.

By capturing details of his sitters’ bare feet, tattered clothes, soiled faces and hands, and diminutive stature against hulking industrial equipment, Hine made a direct statement about the poor conditions and precarity of these children’s lives.

The Photography Collections, University of Maryland, Baltimore County (P2904), CC BY-SA

Hine’s photographs made a successful case for child labor reform.

Notably, the National Child Labor Committee’s efforts resulted in Congress establishing the Children’s Bureau in 1912 and passing the Keating-Owen Act in 1916, which limited working hours for children and prohibited the interstate sale of goods produced by child labor.

Although the Supreme Court later ruled it and a subsequent Child Labor Tax Law of 1919 unconstitutional, momentum for enshrining protections for child workers had been created. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established restrictions and protections on employing children.

The National Child Labor Committee’s project also included advocacy for the enforcement of existing child labor regulations, a regulatory problem reemerging today as the Department of Labor – the agency tasked with enforcing labor laws – comes under fire for failing to protect child workers.

Lewis Wickes Hine/Library of Congress via Getty Images

The ethics of picturing child labor

A recent surge of unaccompanied minors, primarily from Central America, has brought new attention to America’s old problem of child labor and has threatened the very laws Hine and the National Child Labor Committee worked to enact.

Some estimates suggest that one-third of migrants under 18 are working illegally, whether it’s laboring more hours than current laws permit, or working without the proper authorizations. Many of them perform hazardous jobs similar to those of Hine’s subjects: handling dangerous equipment and being exposed to noxious chemicals in factories, slaughterhouses and industrial farms.

While the content of Hine’s photographs remains pertinent to today’s child labor crisis, a key distinction between the subject of Hine’s photographs and working children today is race.

Hine focused his camera almost exclusively on white children who arrived in the country during waves of immigration from Europe during the late-19th and early-20th centuries. As art historian Natalie Zelt argues, Hine’s pictorial treatment of Black children – either ignored or forced to the margins of his images – implied to viewers that the face of childhood in America was, by default, white.

The perceived racial hierarchies of Hine’s era reverberate into the present, where underage migrants of color live and work at the margins of society.

Jane Tyska/Digital First Media/East Bay Times via Getty Images

Contemporary reports of child labor violations offer few images to accompany their texts, graphs and statistics. There are legitimate reasons for this. By not including identifying personal information or portraits, news outlets protect a vulnerable population. Ethical guidelines frown upon revealing private details of the lives of children interviewed. And, as Hine’s experience demonstrates, it can be difficult to infiltrate the sites of these labor violations, since they are typically kept secure.

Digital cameras and smartphones offer a workaround. Beginning in 2015, the International Labor Organization urged child laborers in Myanmar to become “young activists” and use their own images and words to create “photo stories” – echoing Hine’s use of the term – that the organization could then disseminate.

Photographs of child labor in foreign countries are far more common than those made in the U.S., which leaves the impression that child labor is someone else’s problem, not ours. Perhaps it’s too hard for Americans to look at this domestic issue square in the eyes.

A similar effect is at work when viewing Hine’s photographs today. While they were originally valued for their immediacy, they can seem to belong to a distant past.

But if Hine’s photographic archive of child laborers is evidence of the power of photography to sway public opinion, does the lack of images in today’s reporting – even if nobly intended – create a disconnect?

Is the public capable of understanding the harmful consequences of lack of labor enforcement when the faces of the people affected are missing from the picture?