Ray Lawler, who died this week at 103, was one of the artists responsible for establishing the first non-commercial repertory theatre in Australia – the Union Repertory Theatre Company, now Melbourne Theatre Company – and the writer of its best-known play, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll.

It is impossible to think of the two achievements separately. So pronounced was the Doll’s success, it cemented the position of the company. The story of the production of the play is the story of the rise of the Union Theatre.

Both are inception events for the structure, outlook and values of Australian theatre today.

The ‘non-existent’ Australian plays

Lawler was born in Footscray in 1921, leaving school when he was 13 to work in a factory. Taking acting classes whenever he could, he started writing plays during the war after being rostered on night shift.

His first job in theatre was on the vaudeville circuit, playing “straight man” to American comedian Will Mahoney. In 1953 came an all-important meeting with John Sumner, founder of the Union Theatre, and the man who would lead it for 35 years.

Sumner persuaded Lawler to try directing, and Sumner prevailed upon Lawler to let the Union Repertory Theatre Company produce the Doll.

The Doll was not an obvious choice. In 1954, it shared first prize with Oriel Gray’s The Torrents in a playwrights competition. But this meant little. Australian plays often achieved literary recognition. It was getting them staged that was the problem.

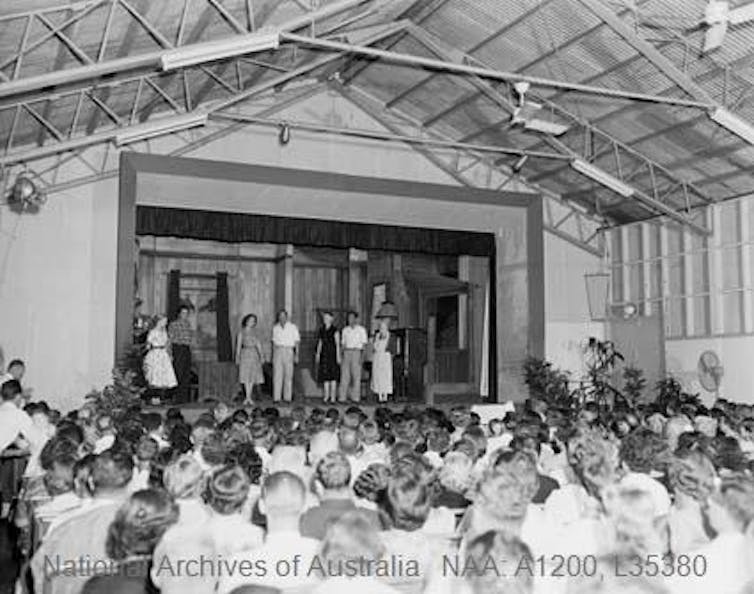

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2023., CC BY

Challenges continued into rehearsals. In 1965, Niall Brennan, the Union Theatre’s front of house manager, recalled:

The theatre in those days was an imported thing; Australian plays, in commercial terms, were virtually non-existent […] The play was set in Carlton, literally almost over the road from the theatre. It was very hard for everyone to realise that we were so close to home. Was it a play about shearers and wombats, muttered one critic?

On November 28 1955, the Doll opened. There had been successful Australian plays before this time, notably Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection (1912) and Sumner Locke-Elliot’s Rusty Bugles (1948). It is the extent and penetration of the Doll’s impact that makes it such a signal work, as well as the quality of its dialogue, characters, and comedio-tragic narrative.

An Australian classic

Lawler’s tale of the deterioration and collapse of the unconventional relationship between two Queensland cane-cutters and their off-season, Melbourne-based lovers was both an assault on the wowserism of the times, and a clear-eyed dissection of values we would now call masculinist.

Unlike other plays of the 1950s, it retains its force and appeal. It is one of the few we can justly call an Australian classic.

Supported by the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust (predecessor to Creative Australia), the Doll toured nationally, Lawler playing the role of Barney.

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2023., CC BY

With the help of Lawrence Olivier, the production then transferred to London’s New Theatre, where it had a similar seismic impact on British audiences, running for over eight months, and winning the Evening Standard Award for Best New Play.

Ken Tynan, the rising star of theatre criticism, wrote of Lawler’s “respect for ordinary people”, amazed at his ability to portray working class characters who were neither incidental nor the butt of class humour. Not until John Osborne, Arnold Wesker and Shelagh Delaney did English drama manage a similar feat.

In 1959, the Doll was turned into a film by Hecht Hill Lancaster. In 1996, it was adapted as a chamber opera by Richard Mills.

A singular event

Lawler had a long career in theatre, but never repeated the triumph of the Doll. In 1957, he left Australia to live in Denmark, Britain and Ireland. Returning in 1975, he rejoined Sumner at the Melbourne Theatre Company until both retired in 1987.

Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1975 and 1976, Lawler wrote two prequel plays, Kid’s Stakes and Other Times. Together, they make up The Doll Trilogy, complementing other trilogies in the Australian repertoire such as Peter Kenna’s Cassidy Album (1978), Janis Balodis’ The Ghosts Trilogy (1997) and Jack Davis’ The First Born Trilogy (1988).

In retrospect, two things can be said about the Doll’s success.

First, it is easy to take for granted and fall into rote deprecation of its influence, like the theatre critic Harry Kippax when complaining about a rush of subsequent plays he dubbed “the Doll clones”. Playwrights are not responsible for the drama they inspire, only the work they create. The Doll remains a singular event for Australian theatre, and for Australian culture more broadly, as it has tacked away from its British colonial origins.

Second, while many Australians have heard about Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, and a good proportion have seen it, the play remains largely unproduced overseas. Here, the drama’s strengths may count against it. The authenticity of language and character that grabbed audiences in the 1950s, and remains impressive now, is hard to reproduce for non-Australian actors.

The power and the challenge of the Doll is that it resists globalised interpretation: it remains supremely and stubbornly an Australian play.

The last word can perhaps be given to Brennan about that opening night audience:

None of us could understand it. The jinx [on Australian drama] had just gone! They clapped the house curtain when it went up, and they clapped the set. They clapped every actor who came on and the roars which greeted Ray’s own entrance were tremendous. When the curtain came down at the end, the theatre almost shook.