After media outlets breathlessly described the late John Olsen as a “genius”, I found myself humming The Chasers’ Eulogy Song.

This is perhaps a bit unfair, but the hyperbole surrounding Olsen’s death seems to have crowded out any assessment of his real and lasting achievements as an artist. There is a danger here.

Hyperbole invites a reaction, which is not always kind. It is still hard to have a dispassionate discussion on the merits (and otherwise) of Norman Lindsay, an artist often called a genius in his lifetime.

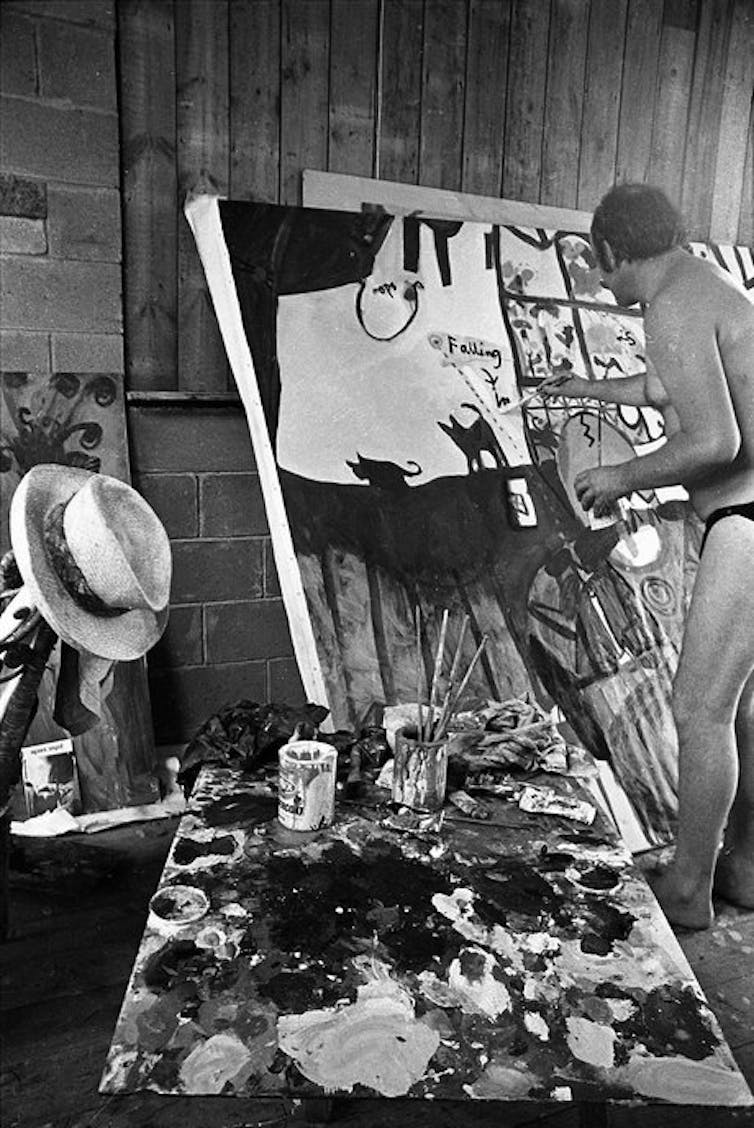

Art Gallery of New South Wales Archive

John Olsen and Australian art

To understand Olsen, and his importance to Australian art, it is important to give some context. He emerged from that generation of Australians whose childhood was coloured by the deprivations of the second world war, and whose adolescent experience was of an expanding, changing Australia.

War meant that he finished school as a boarder at St Josephs Hunters Hill, while his father fought in the Middle East and New Guinea and his mother and sister moved to Yass in rural New South Wales.

His ability to draw meant that he escaped the tedium of a clerical job by becoming a freelance cartoonist while moving between a number of different art schools, including Julian Ashtons, Dattilo Rubio, East Sydney Tech and Desiderius Orban’s studio. As with other young artists of his generation, he was especially influenced by the experimental approach and intellectual rigour of John Passmore.

He found visual stimulation in Carl Plate’s Notanda Gallery in Rowe Street, a rare source of information on modern art at the time. Rowe Street was the creative hub for many artists, writers and serious drinkers who later became known as “The Push”. The informal exposure to new ideas on art, literature, food, wine and great conversation was more effective than a university. He learned about Kandinsky, Klee, the beauty of a wandering line, the poetry of Dylan Thomas and T.S. Eliot.

Olsen’s first media exposure was as the spokesman for art students protesting at the rigid conservatism of the trustees judging the Archibald Prize. There were no complaints about the Wynne Prize, which had exhibited his work.

Art Gallery of NSW

The ‘first’ Australian exhibition of Abstract Expressionism

The friendship between Olsen and fellow artists William Rose, Robert Klippel, Eric Smith and their mentor John Passmore, led to the exhibition Direction 1 in December 1956.

An art critic’s over enthusiasm led to it being proclaimed as the first Australian exhibition of Abstract Expressionism, and its artists as pioneers of modern art. As a consequence, Robert Shaw, a private collector, paid for Olsen to travel and study in Europe. This was a transformational gift, coming at a time before Australia Council Grants, when travel was expensive.

He travelled first to Paris, then Spain where he based himself in Majorca and supported himself by working as an apprentice chef. The fluid approach to learning he had acquired in Sydney was enhanced in Spain. He saw, and appreciated the Tachiste artists, but took his own path, remembering always Paul Klee’s dictum that a drawing is “taking a line for a walk”.

Art Gallery of NSW

That Spanish experience was distilled in the exuberant works he painted after his return to Sydney in 1960. Spanish Encounter paid tribute to the impact of this culture that continued to intrigue him, its energy and its apparent irrationality.

But he also found himself enjoying the “honest vulgarity” he found in the Australian ethos, leading to a series of paintings which incorporated the words you beaut countryin their title. Olsen’s confident paintings of the 1960s easily place him as the most influential Australian artist of that decade.

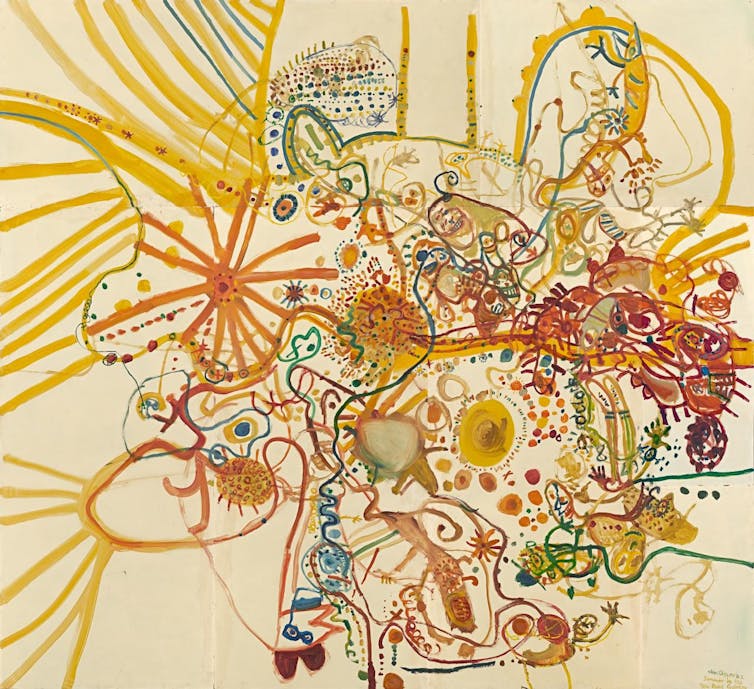

National Gallery Victoris

Five Bells and landscape

In 1972, Olsen was commissioned to paint a giant mural for the foyer of the concert hall at the Sydney Opera House. Salute to Five Bells takes its name from Kenneth Slessor’s poem of death on the Harbour, but is more about elements of subterranean harbour life.

The heroic scale of the work meant that he worked with a number of assistants to paint the dominant blue ground. When the mural was unveiled in 1973, it received a mixed response. It was too muted in tone to cope with the Opera House lighting, too sparse in content, too decorative.

In the following years, Olsen turned towards painting the Australian landscape and the creatures that inhabited it. In 1974, he visited Lake Eyre as the once dry giant salt lake flooded to fill with abundant life. He made paintings, drawings and prints of the abundance – both intimate views and overviews from flying over. Lake Eyre and its environs was to be a recurring motif in the art of his later years.

While these works were commercially successful, and many were acquired by public galleries, Olsen was no longer seen as being in the avant garde. He was, however, very much a part of the art establishment and his art was widely collected.

Art Gallery NSW

A man of his generation

The aerial perspective of many of his later decorative paintings could seem to have echoes of Aboriginal art. Indeed, when the young Abdul Abdullah first saw Olsen’s paintings in 2009 he at first assumed Olsen was an Aboriginal artist.

It was therefore a surprise to many when in 2017 Olsen mounted a trenchant attack on the Wynne Prize after it was awarded to Betty Kunitiwa Pumani for Antara, a painting of her mother’s country.

Despite some visual similarities to his own approach to landscape he claimed her painting existed in “a cloud cuckoo land”. In the same interview, he attacked Mitch Cairns’ Archibald-winning portrait of his wife, Agatha Gothe-Snape, as “just so bad”.

From gum trees to cities to sweeping deserts: how 125 years of the Wynne Prize traces Australia’s shifting relationship to our landscape

While it is not unusual for the radical young to become enthusiastic reactionaries in prosperous old age, there was a particular lack of grace in Olsen’s response to artists who were not a part of his social circle or cultural background. He was in this very much a man of his generation, with attitudes and prejudices that reflect the years of his youth.

Looking at Olsen’s paintings of the 1950s and ‘60s is a reminder that there was a time in Australia when brash young men could prove their intellectual credentials by quoting Dylan Thomas while making a glorious multi-coloured paella in paint.