It’s going to be a bumper time for space missions in 2024 – especially to the Moon, our nearest neighbour. And that’s following on from an already epic 2023.

I’m a laboratory scientist, so I always like to have a “proper” sample to analyse. Rather than peering through telescopes to look at the stars, I prefer to see them in a vial in my lab. My technique of choice is to burn the material to ashes while measuring the organic compounds and other species that are liberated in the process.

So it was a great delight to see the safe return of Nasa’s Osiris-Rex mission from asteroid (101955) Bennu in September 2023. It was an even greater pleasure to receive a few precious crumbs of Bennu to study.

CLPS missions

Nasa’s series of Commercial Lunar Payload Service (CLPS) missions, many of which will launch in 2024, are set to bring a variety of instruments to the Moon. These missions are built and launched by different private companies under contract from Nasa.

The CLPS programme is part of Nasa’s Artemis initiative to continue human exploration of the Moon. One of the main aims of the programme is to investigate the possibilities of using lunar resources as fuel – hence, some of the instruments on CLPS-1, aka Peregrine, are designed to assess the amount of hydrogen on the lunar surface. In fact, my colleagues at the Open University have built an instrument for doing so.

CLPS-2 is timetabled to launch in early January 2024, and there are four other CLPS missions planned for launch throughout the year. That is the good thing about the Moon – it’s so close that there aren’t many worries about launch windows (no complicated orbits to compute) or distance to travel.

Indeed, it is hoped that human exploration of the Moon will take a small step forward, possibly as early as November 2024, when Artemis II orbits the Moon for several days. One of the astronauts on-board will be female – definitely a giant leap in what has, until now, been a solely masculine exploration of our nearest neighbour.

Trailblazer

Continuing the lunar theme, Nasa’s Trailblazer mission travels to the Moon to understand where any water is situated. Is it locked inside rock as part of the mineral structure, or is it deposited as ice on the rocky surface?

Trailblazer is currently scheduled for launch in the first quarter of 2024. However, no precise date has been confirmed. It’s a small mission, part of the Artemis human lunar exploration programme.

Chang’e 6

The launch of Chang’e 6, the latest Chinese mission to the Moon, is planned for May 2024 and is intended to bring material back to Earth. This is particularly significant because the spacecraft will collect material from the lunar farside – the South Pole Aitkin Basin.

This is a region where it is believed there is abundant frozen water. We do not have any samples of material from this part of the Moon – and although any ice will be long gone by the time the samples are back on Earth, it is anticipated we will learn a lot about this unexplored region and its potential as a source of water for human visitors.

Hera

In September 2022, Nasa’s Dart mission encountered a system consisting of two asteroids called Didymos and Dimorphos, and crashed into Dimorphos (the junior partner). The impact had a purpose: to see if such a collision could divert the asteroid in its path – a necessary goal if ever Earth were to be the target of a direct hit by an incoming asteroid.

Esa/wikipedia, CC BY

Two years later, the European Space Agency’s Hera mission will launch to visit the same pair of asteroids. It is not designed to hit either body, but to measure the effect of Dart’s earlier impact. At the time of the collision, the orbit of Dimorphos around Didymos got faster by 33 minutes – a significant movement that showed the path of an asteroid could be deflected.

But what we don’t know (and won’t until Hera arrives in 2026) is how effective the impact was. Has Dimorphos remained in its new orbit, bounced back into its old orbit, or continued to speed up? Hera will investigate in detail – and its results will help to define Earth’s planetary defence protocol. Assuming, that is, we take notice.

Europa Clipper

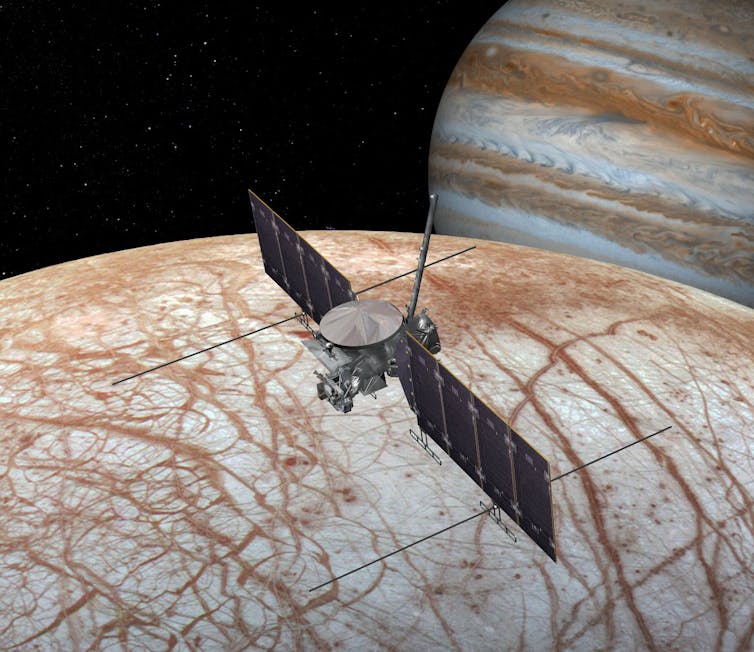

Launching almost at the same time as Hera is a Nasa flagship mission: the Europa Clipper to Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa.

This mission has been long-awaited, ever since the Galileo mission first showed us views of Europa’s icy surface in the late 1990s. Since then, we have learnt about the ocean that lurks beneath the icy shell. Excitingly, Europa may host life in the form of a substantial fauna analogous to the animals that live on the deep ocean floor around hydrothermal vents.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Europa Clipper will fly past Europa between 40 and 50 times, taking detailed images of the surface, monitoring the satellite for icy plumes – and, most importantly, looking to see whether this moon has the conditions suitable to support life. The mission will also investigate whether Europa’s ocean is salty, and whether the essential building blocks of life (carbon, nitrogen and sulphur) are present.

Sadly though, it is not until 2030 that any of these observations will be transmitted back to us, so we will have to wait patiently until then. The investigation will be complemented by observations from Esa’s Juice mission, which is currently on its way to Jupiter.

MMX

I began this article with mention of my delight at the return of material from Bennu. I will finish it with my anticipation of further delights to come. I know I have mentioned return of material from the Moon – but in fact, I am much more excited by the prospect of material returning from another moon. The moon in question is Phobos, one of the satellites of Mars.

The launch of the Japanese Space Agency’s Martian Moon Exploration (MMX) mission to Phobos is currently scheduled for September 2024, and designed to return material to Earth in 2029.

I’ll be 70 by the time the material comes back – but, I hope, not too decrepit to take pleasure in analysis of a unique sample from an enigmatic body.