In 1992, in Esher Library southwest of London, England, Josephine Andrews and her mother, Christine, collected blankets to donate to Kurdish refugees of the Gulf War.

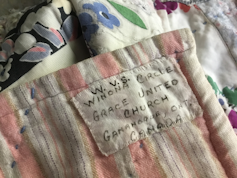

Among the pile of donations, the two women discovered a patchwork quilt that stood out for its vibrant cornflower blue stitches, embroidery and floral patterned fabrics, as well as the remarkable cloth label inscribed by hand: “W. V. S. WINONA CIRCLE GRACE UNITED CHURCH GANANOQUE, ONT. CANADA.”

(Town of Gananoque Civic Collection), Author provided

Made across the Atlantic in Ontario during the Second World War, this quilt was a historical artifact that the Andrews safeguarded for three decades before repatriating it in 2021 to Gananoque, Ont., a small tourist town east of Kingston with a rich military history.

The quilt’s repatriation has fuelled the retrieval of additional lost quilts, each with its own story to tell. Quilts made of different pieces of cloth, like the Winona Circle, tell the story of the women’s resourcefulness and artistic capacities in the face of the war’s rationing and shortages.

Author provided

Quilt-making during the war

During the Second World War, Canadian women made an estimated 400,000 quilts, though the Canadian Red Cross’ provincial records of the quilt production are incomplete with several years missing, and there are probably many more.

These quilts were shipped overseas to provide comfort not only for the soldiers on the front lines and in hospitals, but predominantly for British families who had lost their homes in the German bombing of England. Today, these surviving quilts are extremely valuable for the stories they convey about Canadian women’s war labour and artistic expression.

The deft yet varied stitching patterns of the Winona Circle quilt tell us that it was the product of a community of war quilters. During the mid-19th century quilting bees rose to prominence as feminized social practices and spaces of neighbourly connection.

Quilting bees gained new popularity during the First and Second World Wars. Women’s Institutes, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, the Canadian Red Cross and countless community and private groups mobilized women and opened make-shift workspaces including in libraries, homes and schools for charitable war-time production.

(Private Collection), Author provided

Telling women’s stories

As cultural artifacts, these war quilts unearth a myriad of information about their creators and users. The details embedded in the quilts tell a story of the women’s collective war effort. These quilts are a testament to a broader legacy of Canadian women whose volunteer work was sidelined, under-recorded and under-researched after the war. As beautiful lost artifacts, these quilts are a visual emblem of Canadian women’s heritage which is too often forgotten in the masculine scholarly accounts of war and nation building.

The quilts highlight women’s labour during world wars. Second World War quilters greatly benefited from the teachings of those who had honed their skills during the First World War, making signature quilts and stitching donors’ names with red thread into white quilts, echoing the Red Cross brand.

Raffled to raise funds for the war effort, most of these quilts remained at home in the communities that made them. In contrast, the Second World War quilts have lingered in the shadows of history in the recipient countries overseas.

An estimated 300 surviving quilts remain overseas, requiring research, analysis and ideally repatriation. This is a focus at the Modern Literature and Culture Research Centre at Toronto Metropolitan University. Research Fellow Joanna Dermenjian has participated in the repatriation of four quilts and a team is dedicated to creating an open access digital archive.

(Private Collection), Author provided

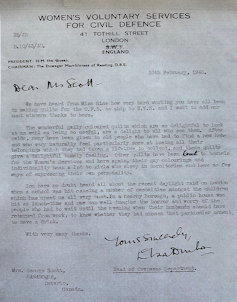

Letters of gratitude

This effort is part of a broader feminist scholarly effort to shine a light on Canadian women’s war labour and heritage. Feminist historian Sarah Glassford has shown that quilting was an activity that also involved Canadian children, like the first-grade branch in Ontario, where participants knitted quilt squares at school for the Junior Red Cross during the war.

Author provided

These quilts were sent overseas to the British children suffering the effects of the blitz who in turn sent letters of gratitude, some of which have survived in family archives.

By interviewing volunteer quilters during more recent conflicts, family studies scholars Cheryl Cheek and Robin Yaure have shown that this affective element is a powerful motivation for volunteer quilters. It leaves them with a sense that they are helping others during a difficult shared crisis. The recipients’ expressions of gratitude can even help the donor with the healing of their own trauma and grief.

In a letter from February 1943, Elsa Dunbar, the Head of the Overseas Department of the Women’s Voluntary Services, thanked the women of Gananoque for “the wonderful gaily coloured quilts which are so delightful to look at as well as being so useful” against the backdrop of a recent “daylight raid on London.”

The quilts provide a testament to Canadian women’s heritage, validating their contributions during difficult times — however belatedly. They speak of the artistic labour preserving powerful women’s stories of hardship, community support and humanitarianism. Each of these quilts speak of a gendered story of the Second World War — long lost stories that remain to be told.