Humans like plants. We like seeing them change the colour of their leaves throughout the year. They connect us to nature even if we live in a big city. But most people don’t think that much about the lives of plants, and least of all, about their sex life.

Because plants don’t move around much, it is common to think they lead boring lives. But today I want to convince you that they can be more interesting than you give them credit for. And for that, I will focus on people’s usual favourite plants: the ones that flower.

Many people think of plants as nice-looking greens. Essential for clean air, yes, but simple organisms. A step change in research is shaking up the way scientists think about plants: they are far more complex and more like us than you might imagine. This blossoming field of science is too delightful to do it justice in one or two stories.

This article is part of a series, Plant Curious, exploring scientific studies that challenge the way you view plantlife.

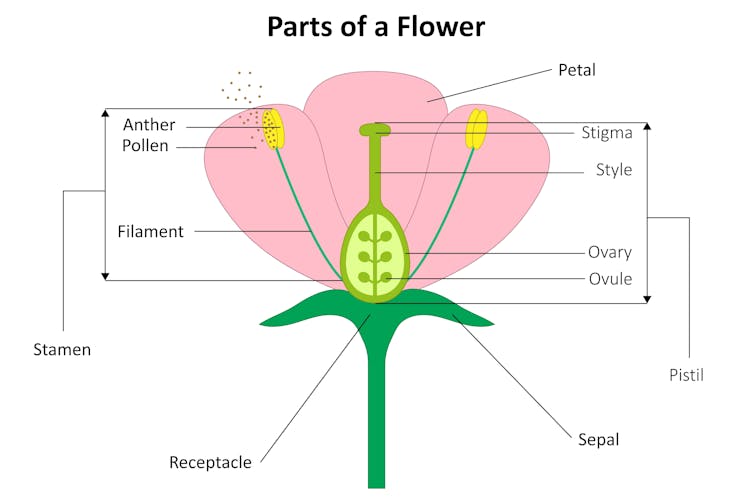

About 90% of flowering plants are hermaphroditic, which means that their flowers have both male and female function. This is what we call perfect flowers. Take the tomato for example. If you open one of its flowers, you will see it has an ovary (part of the female organ) and anthers with pollen (part of the male organ).

MarinaSummer/Shutterstock

In tomatoes, pollen from a flower can pollinate the ovary of the same flower. This means that a tomato plant doesn’t need another tomato nearby to reproduce. Pretty convenient, especially if there are not many other plants of your species around.

Ferlx/Shutterstock

However, this is not the case for all hermaphroditic plants. Some of them can’t self-pollinate, like apples. In those species you do need two individual plants to produce fruit.

Things get more complicated. Scientists think that the first flowering plant to appear on earth was probably hermaphroditic. But what about this other 10% that are not hermaphroditic? What are they and where do they come from?

Let’s dive in.

The alternative to perfect flowers is unisexual flowers, which have either an ovary or anthers with pollen. In some species, male flowers and female flowers grow from the same individual. This is what we call monoecious plants. The plant has both male and female functions but separated in different flowers. Often, these flowers appear at different times of the year, which doesn’t allow the plant to pollinate itself.

There is another alternative to this, which is the total separation of sexes in different individual plants. Willows are one example. In this species, one willow tree will have only male flowers or just female flowers. So, a willow tree can be male or female, more like we are used to in animals like mammals or birds.

This separation of sexes in plants is called dioecy. One reason why dioecy may evolve is because of the negative effects that self-pollination can bring. It’s similar to how humans reproducing with relatives can give their offspring a higher chance of diseases.

Shutterstock collage

But that’s not all. A small proportion of unisexual plants have systems that seem to be in between hermaphroditism and dioecy. The system is called androdioecy when you can find hermaphroditic individuals and males within one population. An example of this is a herb native to California, US, called the Durango root. This system is rare in nature.

Jared Quentin/Shutterstock

The alternative system is called gynodioecy, and it is the other way around. It is a system where females coexist with hermaphrodites. This happens in some wild strawberries.

Lastly, in some cases, male and females have been found alongside hermaphrodites. Some researchers call this trioecy (three sexes). And for this one, one example is the tasty papaya.

Exploring evolution

I mentioned earlier that hermaphroditism is probably the original sex determination system in flowering plants. So how did the other systems evolve from it?

In plants, as in many animals, sex is mostly determined by genes. This means that a seed will become a male or female plant depending on what their DNA says. Studying genetics has never been easy. But it has become easier over the last few decades, with technologies that allow us to study the genes in more detail.

Before this technological revolution, most studies were done in what we call model organisms, like mice, flies and some specific plants like thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana). But now, studying other organisms is becoming increasingly easy. This has allowed scientists to see that in nature there is a lot of variation in sex determination. If we take dioecy as an example, scientists found examples of this system in groups of plants that are not closely related. This means that dioecy has evolved several times. And this is true for the other systems as well.

Gynodioecy, androdioecy and monoecy seem to be a link between hermaphroditism and dioecy. This means that systems can potentially go back and forth, from hermaphroditism to dioecy. And in fact, cases of changes in both directions have been found.

But what about the genes that determine these mechanisms? Scientists have found a variety of genes involved in different species. So, it turns out, there are many ways to evolve a male organism.

This variation in sex determination systems is why studying this topic in plants is interesting. In animals, many big groups, like insects, are dioecious, and they have been for millions of years. This makes it harder to study how dioecy evolved in the first place.

Flowering plants tell us a story about continuous change. The different sex determining systems are connected. If a species evolves separate sexes, hermaphroditism can still reappear in the future. But which is the best system? In nature, there is never one correct answer. It depends on the environment where the plants live and the challenges they have to face.