Brazilian football legend Pelé (1940-2022), whose death was announced in December, inspired countless fans with his skills on the pitch. But his contribution to the off-the-pitch business of football is by no means less impressive.

Following his retirement from the New York Cosmos in 1977, Pelé ran his own company, Pelé Sports and Marketing.

It wasn’t uncommon for retired footballers to take on another job when Pelé first went into business – players weren’t paid the large sums they are today – but Pelé’s success was unusual in terms of scope and recognition, both at home and abroad.

Pelé was ensnared by ‘Brazilian-style racism’ but stood firm as dictatorship tried to keep him playing

Pelé changed the way businesses viewed Brazilian footballers and the sport as a whole. And that changed the football industry beyond recognition.

Brazilian footballers

Brazilian football has come a long way since first reaching the World Cup finals in the 1950s. 1,219 Brazilian players now play professionally in 81 different countries, including four of the top 20 most expensive transfers of all time.

The €222 million (£192 million) transfer of Neymar Jr from Barcelona to Paris Saint Germain in 2017 was record breakingly expensive.

Historically, however, Brazilian footballers were not highly regarded by leagues or international sponsors as football was more European focused. It was Pelé’s success that changed this perception, leading to increased investment and interest in Brazilian football.

Brazilian football and the economy of a nation

The growth of Brazilian football as a business has been a direct result of the national team’s success. Brazil has won the FIFA World Cup a record five times and consistently produced world class players like Pelé, Ronaldo and Neymar.

While the likes of Garrincha (1933-1983) elevated the global “brand” of Brazilian football, the money spinning industry that we recognise football as today is more recent – and it started with Pelé.

Here, Pelé’s success was helped by historical timing – his latter playing years and retirement in 1977 came when international sponsorship had started to come on board with FIFA (Coca-Cola became a sponsor in 1974). But it was his international recognition that shone the spotlight on the Brazilian team.

More sponsorship for the governing bodies meant more money for the sport. In English football (where club finance data is widely available), research shows that wages increased in line with the growth in broadcasting income provided by sponsorship. And with the growth in sponsorship came the need for athlete images for sponsors to use – and Pelé was the obvious first choice.

Sponsorship growth

Footballers are attractive to sponsors because they are popular, visible and able to generate significant buzz and engagement. They are also seen as role models and influencers, able to reach a vast global audience.

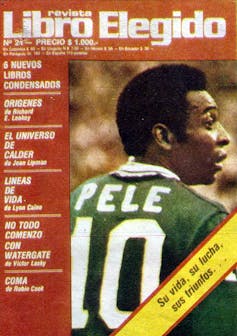

Libro Elegido magazine

Pelé’s international fame and national hero status helped him to use his image after retirement. So influential was that image that Coca-Cola signed him for advertising campaigns in 2001, when he was 60.

There has also been a rise in team sponsorships, where brands are signed as the official sponsor of a football team.

As a result, investment has been made in the construction of new stadiums and training facilities and the hosting of major international tournaments such as the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games.

The product of ‘team Brazil’

Pelé’s global image was also helpful in raising the profiles of his clubs. Santos FC became a household name thanks to its most famous player and the New York Cosmos, too, benefited through global recognition in markets that US football had not previously reached, such as India.

The same is true of the Brazilian national team. The 1950s were a buoyant time for the Brazilian economy, which created an ideal atmosphere for its football industry to grow. Pelé led the charge, with Brazil being crowned world champions in three of his four FIFA World Cups.

This created a product of “team Brazil” at a time when sponsorship was becoming an increasingly integral part of football.

But with growth also came issues. Corruption within both the Brazilian football federation and FIFA have been well documented. Pelé himself was vocal in his criticism of the state of football administration in Brazil during his time as the country’s extraordinary minister for sport.

The economics of football meant vested interests and politics made use of the culturally important team, a legacy still in existence today.

Regardless of the issues, Pelé’s legacy of Brazilian greatness will march on. As the blurb for his 2007 autobiography stated: “even people who don’t know football know Pelé.”