The quiet Welsh painter Gwen John was not like any other artist, male or female – she was genuinely unique. She was neither an heiress, like most unmarried modernist women, nor a conventional academic artist, like most women who had to make a living with their art.

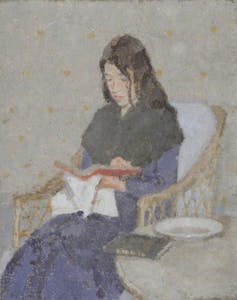

She did not paint loud, macho work that took up a whole wall, nor sexy, objectified nudes, nor abstract forms, like many male modernists. She was fiercely herself, making small, intimate, idiosyncratic paintings that share a definite style and palette over the course of her career.

Ferens Art Gallery / Pallant House Gallery

Alicia Foster’s exhibition at Pallant House Gallery is the first major retrospective of John’s work in decades. Foster is peerless in her expertise on John’s biography and oeuvre, and this exhibition feels like her magnum opus.

It decisively reframes John, placing her at the nexus of a network of friends and influences rather than characterising her as a recluse, as has often been done in the past. “This is a story of connection, rather than isolation,” the first wall text states, “of a woman who was part of the culture of her age”.

The exhibition includes works by some of John’s greatest influences, including some of the big names of French and British modernism: James McNeill Whistler, Paul Cezanne, Edouard Vuillard, Walter Sickert, her brother Augustus John, and her lover Auguste Rodin.

Some of these people John knew, and others she only knew of. There are also works by her actual friends, whose names are much less regognisable: Ursula Tyrwhitt, Edna Clarke Hall (nee Waugh), Ida Nettleship John, Mary Constance Lloyd, and Elinor Monsell. These women were the ones who did not make it – they succumbed to marriage and obscurity. They did not have the ascetic, saint-like drive John had to be an artist at all costs.

Romantic life of an artist

John was born in Wales to respectable but poor parents in 1876. She followed her younger brother Augustus to the Slade School of Art, then the most progressive art school in London, in 1895. A defining force of British modernism Slade tutored many of 20th-century Britain’s greatest artists.

John studied there for four years, existing in the centre of a colourful milieu of talented and vivacious students that included her brother, William Orpen, Ambrose McEvoy, and the friends who are included in this exhibition.

John then travelled to Paris in 1898 to study at the Academie Carmen, under the tutelage of Whistler, who was already a world-famous painter.

Whistler’s teaching, which focused on establishing a full palette before beginning a painting, was something John carried with her all her life. She returned to France in 1903 and never lived again in England, making her home in Paris. She worked as a model and lived in cheap attic bedsits. She was, in many ways, living the romanticised life of a starving artist.

Pallant House Gallery

John modelled for Rodin, the great sculptor, with whom she had a long affair – she was one of many pretty young things in Rodin’s life, but he was the love of John’s.

In the exhibition, a series of Rodin’s drawings of the female nude hang alongside a series of John’s portraits of her beloved cat, Edgar Quinet. The label beside them reads: “Her drawings … give the animal more individuality and presence than Rodin gave the women in his drawings.” It’s true, John’s drawings bring her cat to life, while Rodin’s seem to remove the humanity from his subjects.

She moved to the village of Meudon, on the outskirts of Paris, in 1911, but continued to travel into the city to paint. Her circumstances stablised somewhat after the American collector John Quinn became a regular patron of her work.

In 1913, John converted to Catholicism and built a relationship with an order of nuns who were her neighbours. Some of her strongest and most mature works are a series of portraits she made of these women, some of which are beautifully hung against painted archways at Pallant House.

John’s Catholicism in the second half of her life crystalised what was essentially a sacred calling for her to work as an artist. She was obsessed with recently canonised saints and strove to live her life in a saintlike way. John died while visiting Dieppe in 1939.

Yale / Pallant House Gallery

A quiet but powerful legacy

Pallant House’s exhibition is fundamentally biographical, as many retrospectives are, and is accompanied by a new and definitive biography of John by Alice Foster, the exhibition’s creator. This show resolutely makes the claim that John’s life is its own work of art, and engages with the nuances of a woman who eschewed the norms of both sexes to make her own way.

The opportunity to survey so many of John’s works in one space is surprisingly moving, and expands the stereotype of her work beyond interiors and portraits of lone young women to include plant studies, landscapes, drawings, and of course, her nuns.

Pallant House Gallery

It also made me fully recognise for the first time the real ruthlessness with which John lived her life. The recluse narrative she has been reduced to suggests that she was somehow held back in some way by shyness or poverty.

The story this exhibition tells is much different: John was entirely unwilling to compromise her goal of making art independent of any debt or influence of husband, father, or patriarchal expectations.

She lived selfishly, relentlessly and completely. Her life as much as her art places her at the centre of the modernist tradition and this exhibition valiantly takes on the task of proclaiming her importance in the history of modern art.