Noni Jabavu was the first black South African woman to publish memoirs and one of the first African women to pursue a literary career abroad. She left the country as a teenager to pursue an education and returned intermittently throughout her life. She returned to South Africa in 1977 to research her father’s biography. Some of her best known work became the witty, insightful and politically charged columns she wrote for the Daily Dispatch newspaper. But this pioneering figure had been all but forgotten until writer and academic Makhosazana Xaba and historian Athambile Masola focused their attention on her life and work. Now they have released a book of Jabavu’s columns, called Noni Jabavu: A Stranger at Home. We asked Masola about the writer.

Who was Noni Jabavu?

Noni Jabavu was born in 1919 in Alice, the then-Cape province of South Africa. South Africa had become the Union of South Africa in 1910 and the devastating Native Land Act was passed in 1913 which exacerbated the displacement of Africans in the region. She was the eldest daughter of Florence Thandiswa Jabavu (born Makiwane) and Don Davidson Tengo Jabavu. Her mother was one of the pioneers of the Zenzele self-help groups for women in rural areas. Her parents were prominent figures who often appeared in newspapers and public platforms.

Her father was a politician, writer, and academic at Fort Hare College (present day University of Fort Hare). The college was extremely important as a space for black thinkers and African leaders. She comes from a network of families who were the pioneers in African modernity through their links at Lovedale, Healdtown, Fort Hare and travels abroad. These early intellectuals, teachers, and journalists shaped the cultural exchange as early recipients of missionary education while holding onto African traditions.

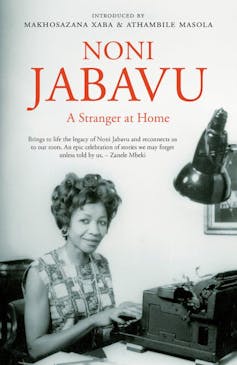

NB Publishers

She left South Africa aged 13 for Mount School, a girls boarding school in York, England. She writes about this departure in her columns where she meets Jan Smuts whom she describes as “Oom Jan”. It is at his house where she meets Arthur Gillet and Margaret Clarke who would be her guardians while she is abroad. In her columns she explains that her family in England were “English tycoons, upper class, bankers, industrialists, conservative liberals”. She remained in England and studied further until her education was disrupted by World War II. It was also during this period where she worked for the BBC radio. In 1941 she married her first husband and a year later gave birth to her daughter Tembi.

Her literary career began while she was in England when her first memoir, Drawn in Colour, was published in 1960. The success of this publication precipitated her appointment as the editor of the New Strand, a literary magazine published in London. This made her the first woman and black person to hold this position in 1961. Her appointment was so significant that she was featured in Ebony Magazine. An Italian translation of the book was published in 1962, further demonstrating an interest in her work. In 1963 her second memoir was published, The Ochre People. Throughout her life she lived in Uganda, Jamaica, Kenya, Zimbabwe to mention a few. In writing she explains the effects of her transnational life on her life as a writer. She returned to South Africa in 2002 and passed away in 2008 while living at the Lynette Elliott Frail Care Home in East London.

Why is she important?

Noni Jabavu’s life is significant because she was a pioneer writer both in South Africa and abroad during the 1960s. Much of her adult life was spent traversing the world, making her part of a network of transnational writers. She crafted a literary career which was unusual for women in the 1960s. Her career inspired the likes of Margaret Busby (editor of Daughters of Africa who became the first black woman to enter publishing as a career in London. On one of her visits home to work on her father’s biography, Jabavu began writing for the Daily Dispatch. She contributed 49 columns to the Daily Dispatch. Her readers were varied and openly shocked by the cheekiness and forthright opinions she held in her columns. They were particularly fascinated by her unconventional love life and the friends she mentioned in her columns. Nineteen seventy-seven was a tumultuous year in South Africa with the 1976 student uprising and the death of Steve Biko in 1977.

How did you come to be interested in her columns?

We were both working on long term projects on Noni Jabavu. Makhosazana Xaba began working on Noni Jabavu while she was pursuing her Masters in Creative Writing in 2006. I began my research in 2017 and much of my research is possible because of Makhosazana Xaba’s work. Many people became increasingly interested in our work but it was frustrating that both her memoirs were out of print. It seemed that one of the ways of addressing this was to garner interest around a collection of her columns which would hopefully ensure that there would be a renewed interest in her work. The columns also presented a different genre to the memoirs she was known for.

What does she address in the columns?

Jabavu’s columns present a variety of themes ranging from the political commentary of the 1970s, to a nostalgia of the life she missed out on as someone who had lived abroad since she was 13 when she left for boarding school in England. She writes about the everyday concerns of a black woman living with apartheid in columns such as “Getting used to colour again”, and “The Special Branch Call”. She addresses the absurdity of apartheid head on. Her columns are also quirky and playful with reference to her love life which her readers are curious about. In “Why I’m not marrying” she responds to readers who “ask me in friendship rather than enmity to tell you more about my personal love life, I respond. Nothing in it to hide”.

Why do her columns matter today?

This collection is historic. Jabavu had planned to compile such a book herself as she shared in a letter to a friend, but this didn’t happen. These columns demonstrate that Noni Jabavu’s concerns from 1970s are still relevant today. Her family’s friendships with politicians such as Jan Smuts as well as upper class English peers complicates how we think about our history and the nature of friendships and race relations. Her frankness about not wanting to marry again is reflective in many women’s choices today who choose not to marry and pursue their careers and friendships instead.

Juby Mayet, legendary South African writer and journalist, remembered through new book

By reintroducing her to a new audience almost 50 years since the columns were published the collection also poses questions about who is remembered and why. This collection is a restorative project in response to the erasure of black women’s writing. Only one of Jabavu’s book was published in South Africa in 1982 (The Ochre People). This is only the second. These gaps in our knowledge of black women’s intellectual labour need to be addressed in order to have a better sense of our history.

The book is available from NB Publishers