These days it’s necessary to have at least a basic level of English proficiency in most research contexts. But at the same time, our collective emphasis on English places a significant burden on scientists who speak a different first language.

In research published today in PLOS Biology, my colleagues and I reveal the enormity of the language barrier faced by scientists who are non-native English speakers.

English has become essential in academic life

Scientists need to know English to extract knowledge from others’ work, publish their findings, attend international conferences, and collaborate with their peers from around the world.

There’s no doubt this poses a significant challenge for non-native English speakers, who make up more than 90% of the global population.

Yet there is a shocking lack of insight into how much extra effort non-native English speakers must invest in order to survive and thrive in their fields.

Making these hurdles visible is the first step towards achieving fair participation for scientists whose first language isn’t English.

We launched the translatE project in 2019 with the aim of understanding the consequences of language barriers in science.

We surveyed 908 environmental scientists from eight countries – both native and non-native English speakers – and compared the amount of effort the individuals required to complete different scientific milestones.

Big hurdles to jump

Imagine you’re a non-native English-speaking PhD student. Based on our findings, there are several major hurdles you’ll need to overcome.

The first hurdle is reading papers: a prerequisite for scientists.

Compared to a fellow PhD student who happens to be a native English speaker, you’ll need 91% more time to read a paper in English. This equates to an additional three weeks per year for reading the same number of papers.

The next big hurdle comes when trying to publish your own paper in English.

First, you’ll need 51% more time to write the paper. Then you’ll likely need someone to proofread your text, such as a professional editor.

That is if you can afford them. In Colombia, for instance, the cost of these services can be up to half the average monthly salary of a PhD student.

The bad news doesn’t end there. On average, your papers will still be rejected 2.6 times more often by journals. If a paper isn’t rejected, you’ll be asked to revise it 12.5 times more often than your native English-speaking counterparts.

Read more:

Long before Silicon Valley, scholars in ancient Iraq created an intellectual hub that revolutionised science

Attending international conferences is key to developing your research network. But you might hesitate to register because you “feel uncomfortable and embarrassed speaking in English”, as one of our participants told us.

If you do decide to go and give a presentation, you’ll need 94% more time to prepare for it, compared to a native-English speaker.

And to stay in academia, you’ll need to overcome all of these hurdles again and again.

Amano et al (2023) / PLOS Biology, Author provided

Language barriers have a widespread impact

These hurdles lead to considerable disadvantages for non-native English speakers. Our study participants expressed feeling “great stress and anxiety”. They felt “incompetent and insecure”, even as they made massive investments of time and money into their work.

We can imagine how such experiences might ultimately drive people out of scientific careers at an early stage.

One particularly unhelpful and shortsighted view is that language barriers are “their problem”. In fact, language barriers have significant consequences for scientific communities more broadly, and for science itself.

Research has shown us that diversity in science delivers innovation and impact. Scientific work conducted by non-native English speakers has been, and will be, imperative to solving global challenges such as the biodiversity crisis.

If indeed, “much research remains unpublished due to language barriers” – as one of our participants said – we could be missing out on substantial scientific contributions from a number of intelligent minds.

What the scientific community can do

Historically, the scientific community has rarely provided genuine support for non-native English speakers. Instead, the task of overcoming language barriers has been left to individuals’ own efforts.

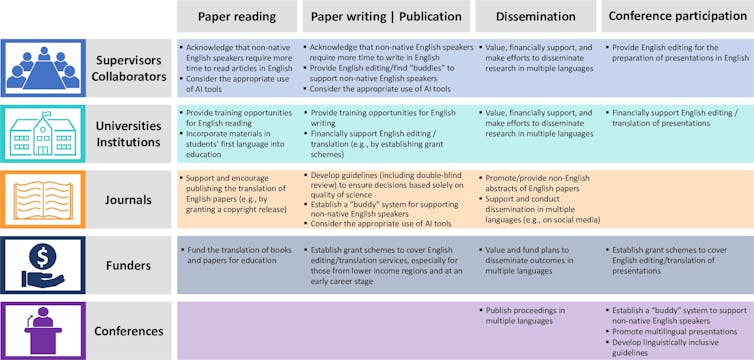

There are a number of actions individuals, institutions, journals, funders and conference organisers can take to change this.

As a first step, journals could do more to provide English editing support to academics (as Evolution has started doing) and could accept multilingual publications (as the preprint server EcoEvoRxiv does).

Conference organisers also have myriad opportunities to support non-native English-speaking participants. For example, last year’s Animal Behaviour Society conference incorporated a multilingual buddy program to improve inclusivity.

Amano et al (2023) / PLOS Biology, Author provided

Artificial intelligence (AI) may have a role to play, too. AI was widely used by our survey participants for English editing.

The British Ecological Society recently integrated an AI language editing tool into its journals’ submission system. However, some journals have banned the use of such tools.

We believe it’s worth exploring how the effective and ethical use of AI can help break down language barriers, especially since it can provide free or affordable editing to those who need it.

It’s time to re-frame

I wish English was my first language.

This comment by one of our participants underscores the way non-native English speakers in science are often viewed by themselves and the whole community: through a deficit lens. The focus is solely on what’s lacking.

We should, instead, view these people through an asset lens. By transferring information across language barriers, non-native English speakers provide diverse views that can’t otherwise be accessed. They have an indispensable role in contributing to humanity’s knowledge base.

The scientific community urgently needs to address language barriers so that future generations of non-native English speakers can proudly contribute to science. Only then can we all enjoy the full breadth of knowledge generated across the globe.

Read more:

3 reasons to study science communication beyond the West