Netflix’s The Pale Blue Eye is an artist origin story with a difference.

The historical noir – set in a beautifully rendered wintry Hudson Highlands, New York – imagines what might have happened if the young Edgar Allan Poe (Harry Melling) had ingratiated himself into the investigation of the apparent suicide of one of his fellow cadets at West Point Military Academy.

The body is found hanging from a tree by the banks of the Hudson. Puzzlingly, the young man’s feet appear to have been on the ground, with his stiff fingers clutching a fragment of a note. His rib cage has been surgically ripped open and the heart removed.

Of course, this scene is not biographically accurate. But it is suffused with the spirit of Poe.

The removed heart recalls his masterful portrait in psychopathy, The Tell-Tale Heart, the story of a man so disturbed by a lodging house mate’s pale blue “vulture eye” that he kills him and dismembers his body so he can hide it under the floorboards.

When the police arrive, he is so convinced he can still hear the dead man’s extracted heart beating that he is driven to confess.

A Poe-esque plot

Poe’s life lends itself to impressionistic, counterfactual treatment, because many of its details – not least his death in 1849 when he was found wearing another man’s suit – remain mysterious.

Depression and language: analysing Edgar Allan Poe’s writings to solve the mystery of his death

Others acknowledged in The Pale Blue Eye, such as his fondness for drink, his liking for female company, his tendency to make enemies, are factually accurate but do not quite explain the dark places where his signature writing obsessions came from.

Getty Museum Collection

We know, for example, what really happened when Poe was at West Point in 1830. He did not even last a year.

Unwilling to continue his military career, he made sure he was court-martialed by neglecting his duty and disobeying orders then ensured dismissal was the only outcome by pleading not guilty.

Poe’s dishonourable time at West Point could lend itself to a more conventional biopic, but this would have missed what writer and director Scott Cooper is really interested in: “the themes that ultimately influence this young unformed writer to become the writer that he became”.

The Pale Blue Eye’s themes indeed crop up repeatedly in Poe’s work: occult ritual and cryptograms, the border between sanity and insanity, the image of the beautiful dead woman – which Poe notoriously described as “the most poetical topic in the world”.

Bringing Poe to life

For the most part Netflix’s film sticks carefully to this brief. It concentrates on developing the whodunit, favouring loose Poe-esque tropes over overt clichés (though at one point a raven inevitably appears, croaking ominously).

Scott Garfield / Netflix

The specific image of a pale blue eye is evoked by the seductive Lea Marquis’s (Lucy Boynton) eyes and the “piercing look” of detective Augustus Landor (Christian Bale).

It can be seen, too, in cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi’s evocative palette, where the pale blue cloaks of the West Point cadets contrast with the monochrome winter setting.

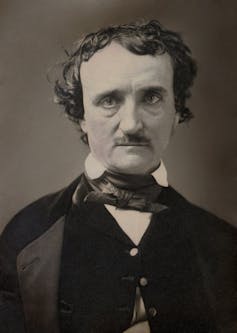

A drawn, bearded Bale is menacing as Landor, the bereaved detective called in to make sense of the case. Henry Melling – known to viewers as Dudley Dursey of the Harry Potter franchise – is uncannily brilliant as Poe, as if the iconic brooding photographs of the author have been brought to life.

Standing on Poe’s shoulders

Both men are drawn together by a liking for drink and books as well the process Poe called “ratiocination” – a combination of scientific reasoning and intuition.

With Poe playing the sidekick and Landor the enigmatic detective, the men form one of the core coordinates of modern detective fiction, which can be dated back to Poe’s groundbreaking 1840s trilogy of detective stories featuring his Sherlock Holmes prototype C. Auguste Dupin (whose name Bale’s Augustus Landor partially evokes).

Scott Garfield / Netflix

As more murders ensue, the mystery deepens. Solving it requires probing the family circle of senior Academy official Dr Daniel Marquis (Toby Jones) and uncovering the nefarious goings on of the Academy.

This far fetched excursion takes The Pale Blue Eye into a brand of horror which jars with the brooding modern noir conventions it began with.

Scott Garfield / Netflix

The acting, which is mainly excellent, becomes hammy. This is most stark in the performance of Gillian Anderson, who unaccountably plays the matriarchal Julia Marquis as if Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham has wandered into West Point.

Poe was hugely influential in the evolution of both the modern horror story and the crime thriller. Yet bringing them together in this way tips The Pale Blue Eye into ludicrous, overlong melodrama.

Poe’s preoccupations were undoubtedly excessive. But in trying to capture so many of them, The Pale Blue Eye itself lapses into an excess which proves too much for one origin story to support.