First Nations readers please be advised this article speaks of racially discriminating moments in history, including the distress and death of First Nations people.

Social historians – among whom I am happily one – are those utter nuisances of people who adamantly insist on reminding others of all the things they are trying so desperately to forget.

Australian historian Manning Clark, channelling Tolstoy, once compared them to deaf people who continually keep answering questions that no-one is asking.

Before this new breed of professional troublemaker appeared in the 1960s, Australian History for the majority was a much simpler and more comforting affair. The stray bits of it I picked up at school in the 1950s told of a strictly peaceful, happy land, peppered with heroic pioneers, doughty diggers and colourful swaggies; and overflowing with sheep and sparkling golden nuggets.

Aboriginal peoples, if they were mentioned at all, were way off on the margins somewhere, throwing boomerangs, going walkabout and eating grubs and snakes. In the most studied Australian history book of this era, edited by Gordon Greenwood, First Nation Peoples literally disappear. They are not in the index, and we are even told by one contributor:

The country was empty […] empty grazing country awaiting occupation.

The principal shock here is not just that this was published without intervention but that no-one who reviewed it pulled anyone up for spreading this academic gas-lighting.

Many older readers can perhaps recall that balmy time, so reassuring for white Australians. I know it has never entirely left my consciousness. It was the only world about which we were “publicly instructed”. But it is a far distant place from the one where we are heading in this essay.

Can more ethical histories be written about early colonial expeditions? A new project seeks to do just that

Explanatory lodestars

The present modish word for the seemingly recent realisation that the Australian story is not all cosy and blameless is truth-telling. In some quarters, this gets presented as a very sudden epiphany. Yet it has a long pedigree. Even while the tortuous frontier process was unfolding in the 19th century, there were always these brave, lone whistle-blowers valiantly attempting to get the truth out and being slammed and shunned for doing so.

With Federation in 1901 and its sense of ebullient nationalism, such voices were gradually stilled and abolished. But then, in the 1960s, with the global burgeoning of decolonisation, desegregation and the diminution of scientific racism following the Holocaust, such voices re-emerged. Even here, in distant, sunny Australia, a small number of us began clearing our throats. Truth-telling was cautiously back on the agenda.

Friday essay: the ‘great Australian silence’ 50 years on

It is hard now to convey how much in the dark we then were on the subject of race. In 1965, I produced for my history honours thesis probably the first extended academic account of an Australian mainland frontier. Every day spent poring over official documents, private manuscripts and old newspapers was startlingly revelatory to me. Virtually everything I was discovering seemed to be so new and beyond the historical pale. It left me feeling exposed and nervous rather than confidently assertive.

At the same time, race relations historian Henry Reynolds was hearing for the first time about Australian frontier struggle, not from within his own land and culture, but as a young teacher, out of Tasmania, listening in astonishment to an African public speaker in Hyde Park, London.

So truth-telling stutters and meanders its unstable and episodic course through our past. It encounters the blank stare of denialism especially on subjects to which a tinge of shame is attached. And Queensland in particular, with arguably the most forbidding frontier experience and the most severe convict penal station, is a ripe candidate for such evasion.

In his recent volume, Truth-Telling. History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement, Reynolds states:

Truth-telling is now more important than ever. What has been a personal choice is now a national imperative […] Denialism is no longer a viable option. A wall of scholarship built by many hands over the last fifty years stands in the way.

Goodreads

So, in building the case for “truth-telling”, Reynolds expands on its “critical importance”. It will “weave new stories and make old ones richer and more complex”. These involve the travails of those who became “victims of great wrong”. Complexity, he writes, will have to replace “simple sagas of heroic achievement”, even if this involves a degree of painful iconoclasm. It will likely produce controversy as “the coals of dormant culture wars are fanned back into life”, fundamental reassessments are made, “reputations are called into question” and “status is re-assigned”.

To this tall order of realigning the consensual interpretive framework, I would add, as a professional historian, that, in the process, we should not forget the often slippery and elusive nature of historical truth itself. For, as every working historian knows, historical accuracy is pursued via vigorous empirical attention to detail in extant, relevant documentation. Fact-finding and truth-seeking need to precede any stern truth-telling.

Dependable analysis also entails a careful awareness of the tensions discovered in texts – a difficult grafting process of measuring opposing knowledges. All this, we hope, will lead us closer to a clearer sense of accuracy, balance and probability in grasping the past.

As historians, we are thus more in the business of producing explanation than in issuing clarion calls for action, doling out blame or pursuing the singular advocacy of a pressing cause. We do know that the past’s “other countries” once had definite and ascertainable structures that both constrained and enabled human beliefs, actions and agency. So, we try to seek these out and explain them in the present. But we cannot re-enter and relive them, and thus fully know them.

“We can’t return. We can only look behind from where we came,” as the song goes. This involves caution, as our hindsight vision is necessarily blurred and shifting, as we speculate continuously upon this elusiveness.

History’s truths are never fixed, total and absolute, but remain in a degree of flux, as they get worried over by researchers, especially as new data and ways of seeing come to light. Thus, truth-telling should embody the caution that history’s truths are specifically contingent and incremental ones, always prone to adjustment. They are like explanatory lodestars, leading us along while keeping us out of the swamps of pure fantasy.

It seems helpful to conclude that such research and writing requires balance between a certain degree of commitment and a modicum of discretion. For even as we try to keep going along this road of attempting truth, any single-minded political crusade or victorious forward march should invite some intellectual circumspection, for the bases of historical truth are invariably constructed on quick or shifting sands.

Why is truth-telling so important? Our research shows meaningful reconciliation cannot occur without it

Much to agree on

With this in mind, let us focus once more on the 2021 volume of Reynolds’ Truth-Telling. My own copy’s text is heavily underscored. The margins are peppered with supportive ticks and asterisks and even the occasional “Good!”. Based upon decades of immersion in racial studies myself, I already know that Reynolds and I have much to agree upon.

We both independently began unfolding the dispossession/resistance model of frontier studies in the early 1970s. We have written on similar themes and reviewed each other’s published work, mostly positively, since that time. From the late 1990s, we occupied the same trench against the Quadrant marauders throughout the farcical, media-driven History Wars.

Both bodies of our numerous writings have dealt with the ongoing partnership between excessive race violence and tight-lipped denial of it. Reynolds asks:

[…] why did the country’s leading post-war historians not notice [frontier violence] at all? Was it oversight or deliberate evasion? How could they think that Australians had been remarkably slow to kill each other, that frontiersmen rarely had to go armed into the outback and [that] we had an inimitably peaceful history … ?

In similar vein, I wrote in 1999 of finding a “glaring dissonance” between the startling documents I was reading and the published preoccupations of Australia’s premier historians such as Douglas Pike in The Quiet Continent or Russell Ward’s outback of congenial mateship.

It was all […] very much like ‘another country’.

So, as I perused Truth-Telling, I was on board with almost everything Reynolds has to say. Especially between pages 184 and 191, where he favourably addresses the statistical accounting of frontier casualties compiled recently by Robert Ørsted-Jensen and myself.

This work nullifies prior estimates suggested by Reynolds by a wide margin: that is, our tabulation of over 65,000 Aboriginal frontier mortalities in Queensland opposing Reynolds’ earlier guestimate of 20,000 dead, Australia-wide over a longer timeframe.

Nevertheless, he is good enough to write that our calculations:

[…] have to be taken very seriously indeed. Once they are widely accepted as they should be, Australian history will never be the same again. It will no longer be possible to hide the bodies or skirt around the violence.

Lukas Coch/AAP

So, one can no doubt appreciate how much I am enjoying this book. Even when the focus of blame for horrific slaughter in Queensland begins to descend rather exclusively onto the shoulders of Samuel Griffith, arguably Australia’s premier legal mind and pre-eminent statesman, I remain in interpretive accord, adding my approving marginalia to the text.

Allow me now to zero in more intimately upon Sir Samuel; as I need to explain the process by which my position on his degree of culpability for frontier violence began to change.

Henry Reynolds: Australia was founded on a hypocrisy that haunts us to this day

‘Hands stained with blood?’

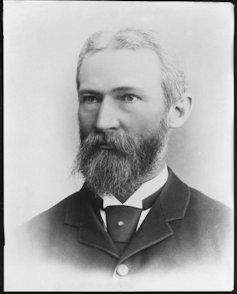

In August 2020, I had been asked by Justice Peter Applegarth to contribute to a group Webinar at the Queensland Supreme Court on the “great man” (twice Queensland Premier, architect of the Australian Constitution and first Chief Justice of the High Court).

This invitation was based not only on my record as a historian but also because both Griffith and I were born in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales. So, initially my talk was constructed as a bit of a romp, accompanying Griffith back to his hometown in April 1887, with “massed choirs”, a big brass band and a mock-Tudor castle.

Matters grew more serious when Ashley Hay, the then editor of Griffith Review, asked me to broaden that talk into a more encompassing essay that eventually appeared in their Acts of Reckoning edition of 2022. In undertaking this, I began to think more comprehensively about Griffith in that 1880s era and the class and ethnic dimensions of both Wales and Queensland as colonial entities.

Queensland State Archives/Wikimedia Commons

Griffith did not emerge looking too splendidly from that original research foray. His 1888 election campaign had helped excite extreme anti-Chinese agitation, though not as vehemently as his successful opponent, Thomas McIlwraith. Several years later, as premier, he helped engineer a crushing of the great Shearers’ Strike of 1891.

Also in 1891, he had not acquitted himself well when ambushed by a Melbourne journalist on the matter of racial outrages in North Queensland.

Two Presbyterian scholars touring the North had returned with a damning report of race relations there. As stated by one of the investigators, Professor Rintoul, it “threw a ghastly light upon […] deeds of lust, reprisal and doom”.

Apparently caught unawares, Griffith had ducked and parried in a less than convincing manner by trying to claim that such yarns were more than 20 years old.

In a stinging and detailed reply letter, Rintoul rebuked Griffith – who, he said, was someone he had regarded in high “esteem” for his vital interest “in the cause of the kanaka and aborigines and of all oppressed people” – for the dismissive sarcasm of his response. He challenged Griffith to further public debate – but Griffith did not respond.

So, I thought: Here we have Rintoul’s contemporary broadside of 1891 alongside Reynolds’ 2021 charges that Griffith must be “guilty of what, after 1945, came to be known as crimes against humanity”.

Furthermore, in the same 2022 issue of Griffith Review that contained my essay, Reynolds had sharpened his attack by declaring rhetorically that Sir Samuel’s “neatly manicured lawyers’ hands were deeply stained with the blood of murdered men, women and children”.

This set me wondering … There must be actual evidence in the primary sources that would enhance this damning case, rendering it not only supportable but probably cementing it. As a troublesome social historian, my bloodhound instincts for deeper empirical research were now aroused. Just how guilty was Griffith among his contemporaries of frontier violence? What body of imprecating evidence could be amassed?

At this point, I felt particularly scathing towards something Griffith had said to the Melbourne Daily Telegraph reporter in January 1891. When challenged over what was he “doing about the blacks”, he had shot back: “What I should be doing”, quickly adding “at all events, few had taken more interest in the welfare of the native population than I have”.

Influenced by Rintoul and Reynolds, I mentally scoffed at this defensive self-assessment. I was intent on finding all the historical data that would nail him. But, as indicated above, historical truth can be shifting and slippery. It does not always take you where you expect it should go.

Truth-telling requires careful truth-finding to precede it. And for such truth-seeking to work, the evidence should lead the way, with the researcher in train – not yet quite knowing the outcome. For one should not start research certain of a destination – one ideally begins in ignorance and curiosity.

If the opposite is the case, one is simply satisfying a confirmation bias – the contrived endorsement of a preconception.

An absence

I began the research odyssey conventionally enough, with a scan of all the secondary Queensland frontier histories for any evidence of Griffith as pre-eminent culprit. To my surprise, he was absent from virtually all the indexes.

It reminded me of Greenwood’s volume and the invisible Aborigines. Not only did Griffith receive no condemnatory mentions – but he also largely received no mentions at all. In the published literature, he didn’t appear to play much of a role.

Throughout my own published writings on Aboriginal dispossession, Griffith does not figure until 2022. And in the most comprehensive recent overviews on frontier violence by Timothy Bottoms, Jack Drake and Tony Roberts, who together give the reader the story in startling and comprehensive detail (over 1,100 pages of text) they find no need to provide him with a single mention.

Allen & Unwin

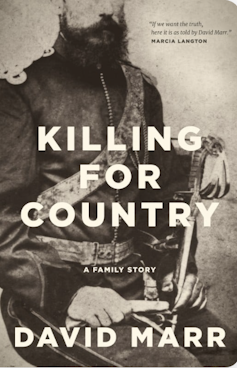

Since my essay was written, David Marr’s massive biographical journey, Killing for Country and Wal Walker’s richly documented study of pastoral occupation, The Squatters’ Grab similarly have nothing to say about Griffith either.

This also applies to Reynolds’ own voluminous frontier work. In over a score of texts produced across many decades, Griffith is mentioned just once, uttering a single enigmatic sentence he will repeat in Truth-Telling, while being confusingly cast as a “young Brisbane lawyer” in 1880. It is the only time Griffith receives a speaking part in his recent, general indictment.

So … curiouser and curiouser, I thought …

Especially as the three texts that do give some significant mentions to Griffith and the frontier tend to cast him in a positive rather than a negative light. These volumes are Noel Loos’ highly referenced Invasion and Resistance, Gordon Reid’s expansive That Unhappy Race and Robert Ørsted-Jensen’s closely argued Frontier History Revisited.

Most recently, in 2023, historians Mark Finnane and Jonathan Richards have contributed more case studies, demonstrating Griffith’s belief that “violence against Aboriginal British subjects was not acceptable and should be dealt with [with] severity”.

By all these researchers, he is shown as intent on pursuing progressive reform and legal balance in face of a colonial society, mainly calling for “blood and yet more blood” – a culture insisting furiously that whites should never be punished for harming or killing non-whites. For this was the nature of the socio-cultural order that anyone considering mitigative reform was up against.

‘I can’t argue away the shame’: frontier violence and family history converge in David Marr’s harrowing and important new book

The documentary records

So, did Griffith pursue frontier reform? Did he rather plot and perpetuate “crimes against humanity” – or even, as lawyer Tony McAvoy, has recently claimed, “war crimes”? – or, at best, did he do nothing to stop them? The hard data, however, was now starting to pull me in the opposite direction, especially as the bumpy research ride moved up a gear into the documentary records.

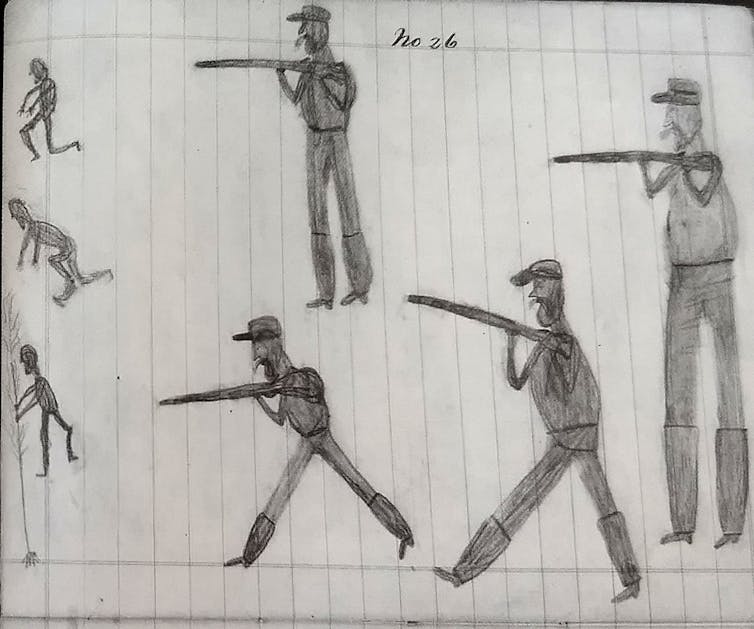

The logical starting point here were the primary sources of the Colonial Secretary’s Office, for this mega-department was directly responsible for the operations of the Queensland Native Police – the main frontier destroyers.

From 1859 until 1897, there were 18 local politicians ostensibly running the Native Police force as Colonial Secretaries across 22 terms of office. A dozen – or two-thirds – of these men were also leading pastoralists in whose immediate economic interests the force operated.

Our mapping project shows how extensive frontier violence was in Queensland. This is why truth-telling matters

Serving as Colonial Secretary for around two years and four months between November 1883 and April 1886, Griffith had the sixth longest incumbency in the role. Prior to this, the two most enduring Colonial Secretaries, Robert Herbert and Arthur Palmer, had overseen 15 years’ service, from the early 1860s to the early 1880s, when racial violence was at its height. They both had large squatting interests and were the force’s greatest apologists.

Griffith held the office when the frontier was radically contracting into the far northern Cape and the outlying lands of the Gulf of Carpentaria. These remote places were both scenes of acutely continuing frontier violence; and Griffith, while Colonial Secretary, officially oversaw all of this – at least nominally.

I suggest “nominally” here, for, as archaeologist and historian Michael Slack points out, regarding the Gulf Country, it was local pastoralists, acting privately, then more formally as Justices of the Peace, who “influenced and ultimately controlled the agenda” of the distant Native Police rather than “a centralised government” in faraway Brisbane. As he argues:

The vast distance separating Western Burke and the […] government in Brisbane, although immense in terms of physical distance, was even greater in terms of authority […] the frontier territory was run on a largely autonomous basis, firstly by the pastoralists and then by their own bureaucratic constructions [ie the JPs, meting out racial ‘justice’]

The same, more or less, might be said of far Cape York. As Queensland reached its fullest dimensions by the 1880s – around two-thirds the size of Europe – its unwieldy size made it increasingly difficult to oversee, service and control administratively. A tendency towards regional excess in the process of land seizure prevailed.

Yet, if we closed off the analysis at this point, we leave Griffith, as Colonial Secretary, politically responsible for frontier warfare during mainly 1884 and 1885. Reynolds writes that while in office he did “little” or “nothing” to assuage the bloodshed and “took no action to protect Aboriginal rights […]”

This led me to ask: Did he really do “nothing”? Or if, rather, he only did “little”, what exactly does “little” mean? Is this to be seen in hindsight, employing modern expectations and looking back with judgmental frowns … Or is “little” to be weighed in the context of his time and place – in comparison and contrast with his contemporary political officeholders? How does one therefore quantify “little” within its immediate historical circumstances?

‘Altogether averse to the Native Police’

So, I started examining Griffith’s procedures in that office as forensically as the records would allow. The results continued to surprise me, as they may now surprise you. The specifics of this are presented in some detail in my recent pamphlet, Samuel Griffith and Queensland’s “War of Extermination”. I shall merely summarise them here.

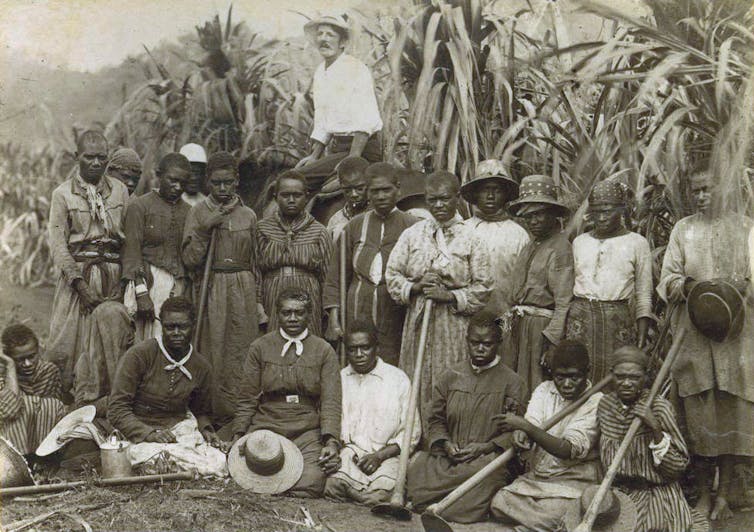

Basically, contingent with Griffith’s considerable raft of reforms over the oppressive Melanesian labour trade in the 1880s, he was attempting to forward local remedies in domestic “native policy”.

Wikimedia Commons

Friday essay: a slave state – how blackbirding in colonial Australia created a legacy of racism

This begins soon after he became Colonial Secretary in late 1883 with moves to prosecute individual white employers of Aboriginal labour in the shameful frontier maritime industries.

This was followed in July 1884 with “the first attempt” to introduce protective legislation for Aboriginal workers, then exploited as quasi-slaves – The Native Labourers Protection Act. Though passed into law, the Bill was emasculated by the pastoral and planter lobby in the Legislative Council.

Concurrently, The Oaths Act Amendment Act was forwarded, allowing First Nation peoples, for virtually the first time, the right to present their evidence in a colonial court of law. Queensland was the last Australian colony to concede this; and Griffith here completed a process he had set in train while Attorney General in 1876. This reduced Aboriginal people’s vulnerability at law, though it did not, of course, obliterate it.

Then, following a much-publicised massacre of fringe-dwelling Aborigines at Irvinebank, inland from Herberton, in October 1884, Griffith began tentative moves against the existing Native Police system. Murder trials were instituted against the white commanding officer, Sub-Inspector William Nichols and the seven implicated Aboriginal troopers.

To Griffith’s disappointment and anger, the vagaries of local white “justice” thwarted the initiative. As a prosecuting attorney, however, he was by now used to this outcome. While Attorney General in the 1870’s, he had unsuccessfully tried to pursue four other cases of serious criminal intent against Native Police officers. He was the first such Queensland official to attempt this.

Such forays in 1875-76 and 1884 were the only efforts to bring a balanced sense of justice to bear upon the Native Police. As a result, officers and troopers were dismissed, though not convicted.

How unearthing Queensland’s ‘native police’ camps gives us a window onto colonial violence

Following the failed Irvinebank trials of October-November 1884, Griffith terminated the responsible Native Police camp (at – excuse the name – Nigger Creek), replacing it with a conventional police station. This led on, during 1885, to a new policy, developed by Griffith in coordination with his Police Commissioner: a measured implementation of what was termed “complete substitution”.

It would have been tactically fatal to eliminate the Native Police in one fell swoop. Several years earlier, while in Opposition in 1880, Griffith had played a leading role – alongside John Douglas, the Parliamentary Opposition Leader – in pushing for a Royal Commission into the force. This had failed in Parliament on the votes by a considerable margin. In 1885, the outcry and backlash against sudden termination would probably have outshouted the furore in 1884 when Griffith tried to have two convicted white murderers executed for killing Pacific Islanders.

Nevertheless, by mid-1885, Griffith was asserting, both privately and publicly, that he was “altogether averse to the Native Police” and telling Parliament he wanted “to abolish [them] […] altogether”. As I acknowledge in my essay:

It is crucial to recognise that […] Griffith was not simply uttering vague phrases, regretting frontier behaviour without any accompanying action. Reynolds is simply mistaken on this. Being tactically astute is not the same as doing [“little” or] “nothing”. Given the clearly exterminatory cast of much of Queensland society […] it would have been politically futile and probably suicidal to have faced colonial electors with the force’s sudden, immediate abolition.

National Library of Australia/Wikimedia Commons

So, between them, Griffith and Police Commissioner David Seymour advanced a more gradual policy. This envisaged that by replacing Native Police encampments with conventional police stations and substituting the illegal, quasi-military armed white officer/native trooper detachments with regular police sergeants, senior constables and one or two unarmed Aboriginal trackers, the original force could be progressively phased out. The process began at Irvinebank, Watsonville and Herberton during 1885.

By the end of the 1880s, there had been around a 65% reduction in Native Police detachments, replaced by some 19 regular bush police stations over much of the North. As historian, Noel Loos observes, Commissioner Seymour, “with Griffith’s instructions and no alternatives” carried the policy of gradualism forward, despite protests from local whites.

In late September 1885, Griffith told Parliament:

The practice of black police making raids through the country as in times past would not be allowed any longer […] It would be intended to assimilate the system as nearly as possible to that of the white police.

To my reading, this is clear evidence of significant policy change. Though Griffith did not succeed in abolishing the force outright, neither did anyone else. It simply faded away by gradual attrition and the frayed endings of the long frontier process. The last camp at Coen was not terminated until 1929.

Furthermore, from around 1883 (sometimes due to local initiatives) ration distribution centres were slowly established, often adjacent to some of the new police stations. The authorities were now observing that many Aboriginal raids were motivated by acute tribal starvation. So, ration stations, where bullocks were killed for meat, and tea, flour, tobacco and sugar sometimes provided, were opened first at Thornborough, Union Camp, Mitchell River, Northcote and Atherton.

Simultaneously, the Griffith regime began encouraging missionary enterprise from 1885 across Cape York, first by Lutherans and later by Presbyterians and Anglicans. These provided sanctuary against frontier excesses and doubtlessly saved lives. As historian, Jasper Ludewig concludes, it was the Griffith ministry:

[…] which gazetted Aboriginal reserves and provided support for missionary measures, including […] access, cash subsidies, rations and limited building supplies. The State’s administration of missionary work fell to the Colonial Secretary’s Department, which received and processed all […] correspondence.

Within several years, he finds, “Christian missions were fast becoming the solution of choice”. By Federation, “close to thirty mission stations had been opened throughout Cape York and the Torres Strait”.

On the side of reform

In sum, what does this demonstrate? It hardly seems to equate with the actions of a leader, singled out from the rest, as pre-eminently guilty of “crimes against humanity” – his hands awash with blood. “Is any other conclusion possible?” Truth-Telling rhetorically asks. Well yes, I think there is.

Indeed, we might cautiously conclude that this tranche of changes represents unique and piecemeal, though progressive and expanding, policy measures. The primary research task discloses:

- A radical attrition of Native Police services

- Implementation of normalised policing

- Novel introduction of Aboriginal court testimony

- An attempted initiative to rein in the frontier “black-birding” of Aboriginal workers

- Prosecution of white frontier crimes inflicted on First Nation peoples

- The burgeoning of missionary enterprise across the North

So deeper primary investigation, to my increasing surprise, had altered my initial conceptualisation. Official efforts from 1883-86 add up to more than rhetorical virtue-signalling. They mark a degree of reformation from outright exterminatory policies employing Snider and Martini-Henry rifles. Has a well-oiled blame crusade simply trampled over all this in a rush towards a sensational, disparaging verdict?

However bad things were in this era – and they were definitely atrocious – liability cannot be laid on any one individual’s shoulders, whomever he may be. Griffith’s reform attempts confronted an implacable socio-cultural order in Northern and Western Queensland – and the challenge often outstripped the response.

A travelling press reporter there in 1880 found one colonist after another, including “highly educated persons […] openly professing the doctrine of extermination”. They look upon “any talk of humanity [or] philanthropy”, he wrote, “as the mere sentimental language of those who do not know what it is to live” there.

Wikimedia Commons

The remainder of Queensland society was not much different. A former Minister of Justice, John Malbon Thompson despairingly told Scottish Catholic missionary, Duncan McNab that year that, “Nineteen-twentieths of the population care nothing about [the Blacks] and the other twentieth regard them as a nuisance to be got rid of”.

Outspoken frontier journalist, Carl Feilberg concurrently agreed that while a certain minority “acted with barbarity”, the vast majority did nothing, as a small minority actively protested.

That majority of enablers were as guilty as the frontier killers, Feilberg reasoned: “[They] condone and share the crime”.

A culture of genocidal intent

What we observe here is a culture of genocidal intent and anyone hoping to confront it was certainly going to have his hands full. Frontier reform was never mentioned at election time – it was a political minefield. So, Queensland electorates had to be slowly cajoled into accepting any redemptive moves. Reform attempts needed to proceed with extreme caution, in an incremental and almost unobserved fashion.

Thus, positive initiatives by Griffith, during his relatively short tenure in the key office of Colonial Secretary, were arguably bold ones in the context of their time and place:

What modern hindsight may condemn as doing “little” or “nothing” may equally be conceived as doing rather much within what was effectively operating as a genocidal culture, where widespread extra-judicial killing was a permissible norm.

Friday essay: ‘killed by Natives’. The stories – and violent reprisals – behind some of Australia’s settler memorials

So, by this point, I had dramatically flipped interpretively and was now asking: Was it in any way fair or reasonable to single out Griffith as principal miscreant and hold him – perhaps due to his enviable accomplishments and gifted, tall poppy status – as a scapegoat, made accountable for the crimes and excesses of an entire society, and thereby isolated for blame?

As Charlie Campbell states in his study, Scapegoat. A History of Blaming Others:

The public is most easily appeased by the creation of a scapegoat. As always, the more serious the crisis, the more important the fall guy […] The urge to blame is sometimes incited in us […] The notion of collective responsibility is one that we prefer not to engage with […]

So, “collective responsibility” is the much harder pill to swallow. Pointing the finger at Griffith, Reynolds, in Truth-Telling declares:

He did little to stop the killing. How then should history remember him? Will his high reputation survive the rigours of truth-telling? Perhaps, more to the point, should it survive?

Yet rigorous truth-seeking shows us that among almost a score of Colonial Secretaries and a dozen or so attorney generals, Griffith appears to be the only one ever attempting anything practically mitigative while holding office.

While I had originally scoffed at Griffith’s defensive claim in 1891 that few had “taken more interest in the welfare of the native population” than himself, I was now beginning to realise he was probably right. He had done more on the side of reform. It is not, of course, a broad claim to make, given that virtually all his Queensland political and legal contemporaries had either done nothing positive for Aboriginal welfare or made the situation worse.

Frontier perpetrators

Griffith appears alone among those directly responsible for the Native Police as well as all those overseeing the law in attempting anything even mildly reformative in the face of chronic frontier ruination and disorder – as well as the widespread public approval of it.

So, must he be singled out as some pre-eminent culprit, allegedly with “blood on his hands” for perpetuating “crimes against humanity” by doing so “little”? Is it helpful to trash a high-level historical reputation in this way in order to watch how spectacularly and far a tall “fall guy” might fall?

Feilberg wrote in 1880 that it was Queensland’s hands, in general, that were “foully bestrained [sic] with blood” – and it is clear there was blood on so many hands in the colony. Over many decades it had been a virtual free-for-all, with no effective legal redress.

A register of the known names of frontier perpetrators, and those in politics and law who had abetted them, as well as all those in whose direct economic interest the brutality and killing had occurred, would be an extremely long one.

There are many such names. Here are some thumb-nail sketches of just a few who might precede Griffith in any compilation of indictments:

Wikimedia Commons

William Forster, Premier of New South Wales in 1859 who bequeathed the Native Police to the new colony. Historian, Wal Walker typifies him as “a most […] vindictive hater of Indigenous Australians”.

As a squatter in the Burnett district from 1848, he had taken up 64,000 acres of Aboriginal lands. In 1849 and 1850, he led reprisal raids against Taribiland and Gurang peoples near Bingara and at Paddy’s Island, heading settler armies of up to 100 mounted whites, allegedly killing hundreds of Aboriginal men, women and children.

George Bowen, Queensland’s first Governor, ignoring official instructions that Aborigines were British subjects, under protection of the Crown, while re-defining his official role as extending “border warfare […] carried out under some control on the part of the government” against “hostile savages’ as his proud “contribution towards the general defence of the Empire”.

Robert Herbert: The first and longest continually serving Colonial Secretary, known as the Native Police’s staunchest friend. He wrote of Aborigines officially as “criminals”, “cannibals” and “very dangerous savages, deficient in intellect”.

He looked forward to their inevitable extinction. He used Native Police to secure Gugu Badhun territory with violence for his investment syndicate, seizing these lands in the Valley of Lagoons, inland from Cardwell.

David Seymour: Police Commissioner for 32 years across 16 colonial governments, directly supervising the Native Police and suppressing evidence of their massacres, as he advanced his substantial financial speculations in gold and tin mining, pastoral landholding and timber-getting across the colony.

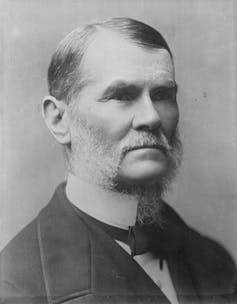

Robert Ramsey MacKenzie: Premier and Colonial Secretary in 1866-67. Established a white-washing enquiry in the Native Police while Treasurer in 1861, stacking the board with squatters holding over 3.5 million acres of Aboriginal lands. Himself a mega-pastoralist, leasing 52 runs – later made a baronet.

Before entering the northern regions in 1840, he was involved, along with his brother, in a mass poisoning of Gringai people at Wattenbahk Station, north-west of Newcastle.

Wikimedia Commons

Boyd Morehead: Colonial Secretary, 1888 to 1890. His family virtually ran the Scottish Australian investment Company, one of the largest speculators in Queensland pastoral holdings.

He stated in Parliament in 1880 that: “If there were no Aboriginals it would be a very good thing”. “There was not a member in the House”, he claimed, “who did not feel they had to be got out of the way”. This “wretched, mean race […] had to go and go they must […] They mainly got only what they richly deserved”.

Anderson Dawson: Queensland leader of the short-lived first Labour Government in the world in 1899. He boasted to the Brisbane Worker, as part of his CV as a sterling white man, that in 1886 at the Kimberley gold-rush, he had played his part in what the paper termed a “nigger massacre”.

Historical research claims between 40 and 100 Kitja people were killed. Dawson subsequently became Minister of Defence in the first Federal Labor Government in 1904.

Beyond individual blame

I could continue with this listing, but this is probably enough to make the point. I think it is true to say that most readers would not have even heard many of these names before – yet Griffith, the outstanding historical personage, is well known – a big scalp, so to speak, and thus readily targeted.

Like him, however, most of these people have streets, suburbs, towns, districts, electorates, rivers or mountain ranges named after them. Unlike Griffith, though, most of them held wide-scale pastoral interests – interests that the Native Police were defending over extended time-frames against very determined Aboriginal resistance.

So, it would seem that a class/communal explanation for the remorseless dispossession might be a better way to determine causation, motivation and responsibility – in short, a pursuit of a systems analysis of colonialism as a more constructive way of grasping the fundamentals of this history. This can establish the driving rationale and structural underpinnings of occupation, rather than pursuing a singular crusade of individual blame for the manifest theft and violence.

This explanation is at first class-based because it is clearly a dominant minority class sector of, predominantly, pastoralists – but also plantation and mine owners – who were the principal land-takers, dependent initially on Native Police sorties and violent raids by their employees to secure the purloined landed wealth.

Using the excellent compilation work of the late Queensland historian, Bill Thorpe, we find there were over 3000 pastoral run-holders in 1876, contracting to little more than 1000 by Federation. These represented only 1.8% of the colonial or migrant population in the 1870s, down to only 0.2% by the 1900s.

But this tiny sector accounted for most of the privately held landholding in Queensland. Furthermore, in the latter stages, it was mostly foreign owned by corporations and banks operating outside of the colony and State.

These people and organisations – often also at centres of political power – were the direct beneficiaries of profit from the captured lands. The various genocidal processes adopted, publicly and privately, to achieve this were in such people’s immediate material interests.

Communally, most of the white colonial population cooperated, in one way or another, with the seizure and displacement process; and a minority of frontier actors took a leading part in inflicting and perpetuating it, thinking they were “advancing civilization” or “extending the margins of Empire” in so doing. Thus, we might conclude, the colonial takeover was class-based in its ultimate economic interest and communally driven in its comprehensive, destructive thrust.

As David Marr puts it in his recent Killing for Country:

Australia was fought for in an endless war of little cruel battles […] Nowhere would the occupation […] prove bloodier than here [in Queensland] and no instrument of state [was] as culpable as the Native Police. Slaughter was bricked into the foundations of Queensland.

In mid-1880, a reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald, travelling around North Queensland, wrote these prophetic words:

Those who consent to such things and those who approve of them must look well as to how they will stand in future times with posterity, when the early history of this country comes to be written.

Goodreads

We people here and now are that “posterity” – and it is imperative that any truth-telling we engage in should be well-targeted, balanced and comprehensive. Truth-telling, as Reynolds advises us, is “complex” – and with that I would agree.

Yet my research indicates that Samuel Griffith did not “consent to such things” nor “approve of them”, although he is neither the untarnished hero of this story nor its exceptional villain. And he was not, as Reynolds’ accounts claim, “especially culpable”. Available primary evidence does not appear to bear this out. “That is”, as John Lennon once famously sang, “I think I disagree”.

Griffith is part of and party to – among so many others – the British Imperial/colonial venture that created, for good or ill, present-day Queensland society. As a socio-economic formation and a culture, we have been very slow to accept how utterly that land-taking venture was steeped in bloodshed – and our collective responsibility, historically speaking, for this.

Yet, is it not ironic that the lone public figure who apparently attempted, however inadequately, to challenge the mayhem should now be freighted with the principal blame for it?

Griffith was neither a monster nor a saint. In determining his specific role, it is probably best not to be too certain in mounting clamorous, angry calls for redress, bearing in mind that truth-telling, where history is concerned, can be multi-layered, elusively structured, endlessly surprising and perhaps at times chimerical.

For, even after the rigorous application of exhaustive research, history remains mercurial and subject to change – within reach without falling into one’s final definitive grasp. The “rigours of truth-telling” warn us never to be too sure of the outcome.

This article is an edited version of a lecture given last night to the Selden Society for the Supreme Court of Queensland and Griffith University.