This is the day we will sink our own home –

it is old, they say, and can’t live forever.

I’m among the ones who must lock the dome

behind us and throw the keys in the river

of stardust in which we’ve swum for so long.

Happy new year! The cry goes up far below

us in waves, while we plot to do great wrong

to this ship in space. No keening in sorrow:

These are my orders. Death first by fireworks,

our vessel burned alive like a sailing boat

lit aflame at sea by men gone berserk

with grief. The saltwater will keep it afloat

as long as it can. For the rest of time

it will lie in pieces, like a heart once mine.

– A sonnet imagining the final astronauts onboard farewelling the International Space Station (ISS) before its deorbit.

For many years now, through writing fictional stories and making experimental films, I have been trying to see things from the point of view of space objects – real ones that have been launched by humans into outer space.

I’ve imagined the inner and outer lives of space objects like Starman (the mannequin launched by SpaceX in a midnight-cherry Tesla); the first sculpture left on the Moon; the International Space Station; and the Voyager spacecraft now in interstellar space. At heart, my goal has been to understand why humans pour so much meaning into space objects.

I’ve become fascinated by the emotional attachments many people – and especially scientists – form with these objects, from small spacecraft to satellites to space stations. Deep emotions (like grief and love) are often expressed for these objects by space scientists, astronomers, engineers and astronauts who would not, in their ordinary line of work, be expected to think at all about their feelings for inanimate machines or space infrastructure.

“Every object humans have launched into the solar system is a statement,” notes the space archaeologist Alice Gorman, and each “tells the story of our attitudes to space at a particular point in time”.

In political theorist Jane Bennett’s definition, an object is enchanting if it leaves humans “transfixed, spellbound” and “struck and shaken”. This is almost always the case for space objects. They seem to give scientists permission to share emotions that would otherwise be kept hidden.

NASA/AAP

Coddled and mourned

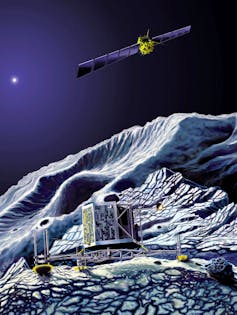

In 2016, the team in charge of the Rosetta spacecraft grieved openly after Rosetta was crashed on purpose into the comet it had been observing. The mood in the control room was described as “funereal”.

Erik Viktor/ESA ASTRIUM/AAP

During a Zoom talk in 2021, Morgan Cable (an Ocean World Astrochemist at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory) was asked by a member of the public what the most memorable project in her career has been.

She responded with raw emotion, paying tribute to the strong bond scientists can form with their space objects, and describing how she felt about the Cassini-Huygens robotic spacecraft launched in 1997 to study Saturn and its moons:

Right near the end of Cassini’s life [in 2015], it was running out of gas, and we didn’t want it to just drift around the Saturn system […] We had cleaned it but hadn’t sterilized it – so we had to put Cassini in a safe place where it couldn’t contaminate other worlds. We did this beautiful swan dive into Saturn, a place with no liquid water, so that we could preserve future worlds – like Encephalus and Titan – for future explorers, without being contaminated.

When we said farewell to Cassini in that beautiful swan dive … [the] spacecraft …[was] part of our family. We grew to love and became a part of it. It was incredibly difficult to say goodbye to that spacecraft.

American astronaut Don Pettit lovingly wrote from the perspective of a real, living zucchini plant grown on the ISS (along with broccoli and sunflower seedlings) to create his wildly popular Diary of a Space Zucchini blog after he’d returned from the station. This little seedling, an object of research, struggles into existence and tries to make sense of the human world around it. In the following excerpt from his blog, “Gardener” is the zucchini’s name for the astronaut who tends to it:

Excitement is in the air. Gardener said we will soon be returning to Earth. Our part of the mission is nearly complete and the new crew will take over for us. I am a bit worried about Broccoli, Sunflower, and me. If Gardener leaves, who will take care of us? And what about little Zuc? He is now a big sprout and ready to branch out on his own. Gardener talked about pressing us. I am not sure what that means; this does not sound good.

NASA TV/AAP

In certain contexts, this “love” scientists feel for space objects can be openly expressed – even for a zucchini being grown in microgravity, for instance, through a whimsical and sweet narrative voice.

This is quite different to the emotional rules usually governing any scientific engagement with objects of study. Anthropologist Anna L. Tsing has observed that natural scientists can be deeply interested “in the lives of the nonhuman subjects being studied,” but “mainly on the condition that the love didn’t show”.

More recently, certain climate scientists have begun to express their own ecological (or climate) grief openly, in spite of the professional pressure to hide their emotions when it comes to their ultimate research subject (or object): our planet Earth.

Yet this taboo against scientists feeling a genuine emotional connection to the objects of their research does not always seem to apply to scientists making, launching or studying space objects.

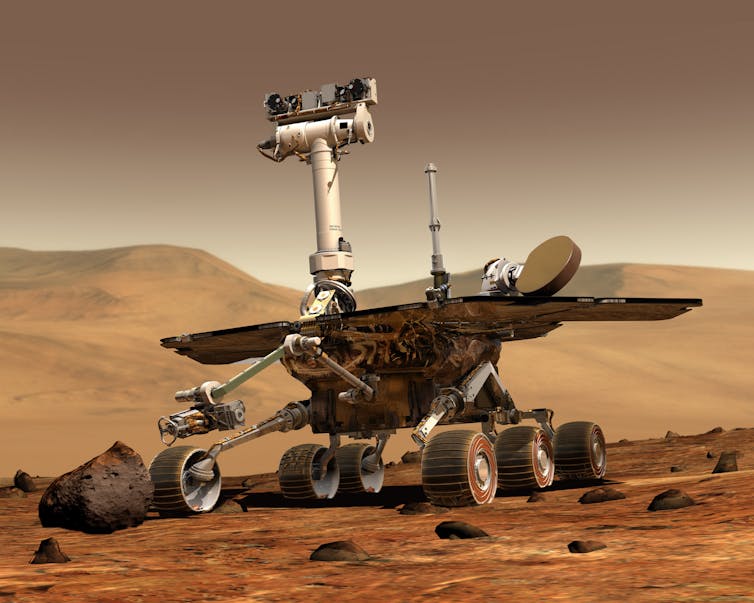

The scientists and technical team in ground control for the Spirit Mars rover mission spoke often of Spirit as if “she” were alive during her seven years of active work on Mars, anthropomorphising Spirit into an object of adoration. Said one team member, “She’s a stubborn old girl and she’s hanging in there, and she is not going to give up”.

The Opportunity Mars rover (Spirit’s twin), simultaneously exploring another part of Mars during the same mission, was gendered as male by the control team. Opportunity got trapped in a dust storm at one stage, and “his” battery power began to drain.

NASA/AAP

Steve Squyres, the lead scientist, describes having “this horrible, helpless feeling because there was nothing we could do … [i]t was like Mars was trying to kill our machine”. Squyres later reflected on all that the two rovers had been asked by humans to do, using a parenting analogy of needing to let a child grow up and become resilient and independent:

When we first built [them], we babied them, we coddled them, we dressed up in funny suits, we had rubber gloves on, we tiptoed around them and were extremely careful […] [n]ow they are scratched, beat up, and dirty.

When Spirit was on her last legs, and the team had to come to terms with the fact that her mission was over, Squyres admitted, “It hit me harder than I thought it would […] emotionally”.

Envoys of humankind

All of these objects are our proxies in outer space. Once they are out there, representing us in places we have been unable to go, they become the “envoys” of humankind (as human astronauts are defined in Article V of the 1967 UN Outer Space Treaty).

This is an impossible task, of course. How can the twin Voyager spacecraft, for instance – the most distant human-made objects, currently in interstellar space – carry the full representational burden of who we are? They are doomed to fail. But maybe we think of them as loveable because of this very vulnerability.

Bruno Latour, the French sociologist and anthropologist of science and technology, was never afraid to inhabit radically different perspectives, including those of objects and infrastructure. He wrote a novel-of-sorts – half whodunnit, half sociological tome – partly from the perspective of ARAMIS, the high-tech subway system planned for Paris in the 1980s that never came into being.

Goodreads

In certain sections of this novel (called Aramis, or the Love of Technology) the system itself speaks, making its case to the humans who essentially betrayed or failed it (engineers, officials, a sociologist) and reminding them it has desires too, but depends on the human and technical networks around it to survive.

Latour is alive to the reciprocal flow of relationships between humans, objects and institutions, and advocates dissolving boundaries between things considered to be artificial and those considered to be natural.

As Australian sociologist of science Annie Handmer notes in her interpretation of this novel, Latour “slowly makes his reader fall in love with this ingenious, complicated, and enchanting train”. He asks us to acknowledge the network of relationships in which we’re entwined with things, networks that have both emotional and social resonance.

The “imagined conversations between components of its engine,” Handmer writes, “evoke an emotional affection in us for the technology that makes it all the more heartbreaking when Latour tells us that ARAMIS died because no-one loved it enough”.

Latour’s approach was particularly useful to me while I was writing from the perspective of the International Space Station in my collection of short stories Only the Astronauts. Like ARAMIS, the ISS is a major infrastructure project, among the most expensive ever undertaken by humans. The ISS, of course, did not fail before it could live, but it has always been dependent for survival on a nexus of human-technical elements made even more complex by its location in space, and the multinational nature of its governance.

The ISS has inspired big emotions like love and awe in humans. One could say it will “die” within the next decade because we aren’t “loving” it enough. The ISS’s international mission and cooperative management will not be sustained for much longer, leading to its inevitable deorbit in the next five to ten years (unless some kind of public-private partnership is created to “rescue” it).

In some mainstream media coverage, this decision to deorbit the ISS has been described as an “abandonment” of the space station.

NASA/AAP

From love to fear

Yet through the course of my research, I began to notice that space objects once deemed enchanting and “loveable” could suddenly start to seem threatening to humans. The ways in which they can survive and thrive outside of our will and designs for them can sometimes shade into a kind of horror of the undead.

Abandoned places and objects that refuse to decay, that persist in spite of no longer having a living human presence to give their existence meaning, become spooky. Our feelings for these objects can shade dark, into uncanny and eerie territory. We love these objects for going where we cannot, but we can also start to fear them for this, and for living so long. They scare us by not dying.

This passage from a recent non-fiction book about space exploration (Ad Astra: An Illustrated Guide to Leaving the Planet) struck me for this reason. Note how quickly the abandoned Russian space station, Salyut 7 – once it persists beyond human use value – becomes the site of a Gothic nightmare:

On 2 October 1984, the Soyuz T-10 crew […] prepared to leave Salyut 7. As they were shutting up shop, preparing the station to be temporarily mothballed in automatic mode, they left the customary crackers and salt on the table as a gift for the next crew […] But after they left and returned to earth, a transmitter malfunction led to a short-circuiting of the electronics and all the electrical systems shut down […] The station was dead […] With its solar panels no longer facing towards the sun, it began to freeze […] Spit would freeze to the walls and icicles hung from the pipes […] The crackers were waiting for them on the fold-down table.

Humans can become haunted by space objects once we no longer know if they are still there or not, or in what form they persist. It has only recently been acknowledged that re-entry particles from objects, satellites and spacecraft burning up in Earth’s atmosphere don’t simply disappear, but form a kind of ghostly toxic dust that may, over time, contribute to global warming. These objects can quite literally come back to haunt us, even if they seem to have dropped out of orbit and disappeared.

Kayla Barron/AP

There is some ambivalence, then, in how we think and feel about space objects. They are our dignified emissaries to other worlds and will be justly rewarded with immortality (and expressions of love, even from hardened space scientists).

Once they are no longer responsive to our commands, however, they might be recast as dangerous trash that can kill us: just one bit of space junk the wrong size hitting the ISS could make it immediately uninhabitable, for instance.

Space objects are sacrificial offerings we make to the universe, sent on journeys into the unknown. They are banal things that suddenly become vibrant objects – spiritual relics – because they have touched the celestial void.

They may depend on us for their survival if they’re in orbit, and we may still have the power to bring some of them back down; but the ones that escape further out will eventually have their freedom and agency, whether we want them to or not.

Every launch of a space object is a birth and a death. For the object, it is the start of a grand adventure, one that – if the object is lucky – may take place outside human surveillance, under cover of the mystery of space.

Space objects resist our interpretations of what they mean, even as we want them to mean so much, even as we feel so much for them. This is an important reminder that it is a political act to take a non-human perspective, and to consider the agency, subjectivity, sociality and power of things – not just living things, but non-living things – in co-making the world.

This awareness that humans are not in total control, and that – as social scientists are pointing out – we have responsibilities to those “non-human beings [that] share our paths” can bring up mixed feelings for us as a species. These are exactly the kinds of feelings that fiction writers and filmmakers can mine.

My invented stories are, in one sense, just another layer of narrative that is being forced upon certain space objects. I can claim that I am on their side, that I write these imagined stories in tribute to their wild spirit, their anarchic and fertile disobedience to human control, or out of the same wells of love and grief that space scientists express for their rovers, or that astronauts express for their space plant seedlings.

Yet in truth, it is in their total and frustrating silence that space objects remain a site of resistance to human meaning-making. Maybe this is why we adore them so much, fear them when they stop responding, and grieve their destruction so openly: because our love for them is unrequited.