Are we, finally, post-COVID?

Reading Lara Feigel’s Look! We Have Come Through!, it feels like we are.

The emotional consequences and aesthetic ramifications of the pandemic will continue to ripple through culture, changing our way of seeing the world, even as we begin to weary of the change. Writers who seemed outmoded or alien to a pre-pandemic worldview will suddenly have new relevance, helping us to understand the emotional landscape of a world riven by disease and crisis.

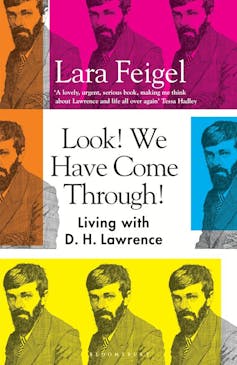

Review: Look! We Have Come Through!: Living with D.H. Lawrence – Lara Feigel (Bloomsbury)

Look! We Have Come Through! offers this idea as a take on literary criticism. Feigel is the author of four books of non-fiction and one novel, all of which combine cultural history, biography and literary criticism. Her latest book is an account of isolating in Oxfordshire with D.H. Lawrence (or rather, with his books) during the locked-down months of 2020. Subtitled Living with D.H. Lawrence, it is a bibliomemoir that places Feigel’s immediate experiences inside the frame of criticism.

Lawrence is a writer whose books and biography provoke either adoration or loathing, depending on one’s taste, politics and patience. He is an ideal companion for lockdown, Feigel says, because he was so expert in the polarities of isolation and proximity.

The approach to critique is engaging, especially if we take seriously Feigel’s thesis that literature gives us “resources for survival”. She contends this is true not simply because of literature’s capacity to open us to otherness, but perhaps more crucially because it allows us to live with negativity and crisis: “to integrate the madness and destruction into a liveable life”.

“One hope from locking down with Lawrence,” Feigel writes, “is to use this time to think through what I see as the purpose of literary criticism – and whether, in the midst of today’s crises, it remains a worthwhile pursuit.”

Each chapter approaches Lawrence’s life and work from a thematic perspective – “Unconscious”, “Sex”, “Parenthood”, “Apocalypse”, etcetera. Interwoven with her critical analysis, Feigel makes a case for Lawrence as a kind of guide to life, or at least a guide to her life:

I have turned to Lawrence for urgent literary companionship, hoping that he will help me make sense of the new world we have found ourselves in.

No name, no body

Look! We Have Come Through! does not have the sense of enclosure and claustrophobia that Rachel Cusk achieved in her recent Lawrentian novel Second Place (2021). Feigel is locking down with her two children and her partner in a cottage in Oxfordshire. She and her family are able to ramble around the UK countryside, observing lambs and cows and snowdrops. They get mired in mud on Cornish beaches and visit Eastwood, the tiny Nottinghamshire town where Lawrence was born and grew up, and from which he eagerly escaped for the wider world of London, Germany, Italy and Mexico.

The polarities of intimacy and isolation, crisis and stasis, are as familiar for us as they were for Lawrence, who lived through a period of social, economic and political upheavals on a global scale, including a world war and a pandemic. He moved around restlessly, searching for community, yet unable to settle. He was a self-made sexual guru who was an obdurate hater; an outsider who sought to excavate human interiority.

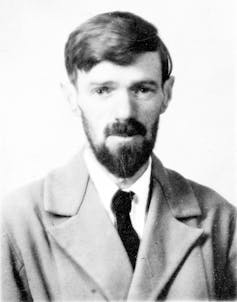

As Feigel points out, Lawrence had many names, yet none of them seemed appropriate. Christened David Herbert, in childhood he was Bert. His cosmopolitan wife Frieda called him Lorenzo – “a name well-suited to his image as a Priest of Love”, Feigel comments, but ill-fitting his identity as the puritan “man of the Midlands”. He signed his letters – even to his mother – DHL.

“For me,” Feigel admits, “he has no name, and neither does he really have a body.” He is a “ghost”, a presence that haunts her but remains tantalisingly intangible.

Ninety years on, what can we learn from reading Evelyn Waugh’s troubling satire Black Mischief?

Grotesque and immediate

It is at this juncture that I should probably confess that I am not a Lawrence expert, nor even a Lawrence enthusiast. In fact, a month ago, if you were to ask me to name the writer I least admired, it would have been Lawrence.

As an undergraduate, I read three or four of his novels with mounting irritation at the hectic, repetitive loops of his sentences – never mind his sexual and racial politics. One of my favourite books is Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm, which skewers Lawrence and his ilk with merciless glee. So my sympathy with turning to Lawrence for self-help was, at the outset, limited.

It is a testament to Feigel, whose prose is commendably clear, that her book is a compelling reading of Lawrence. It caused me to reconsider him and his work. I called up a stack of his novels and a book of his paintings from my university library.

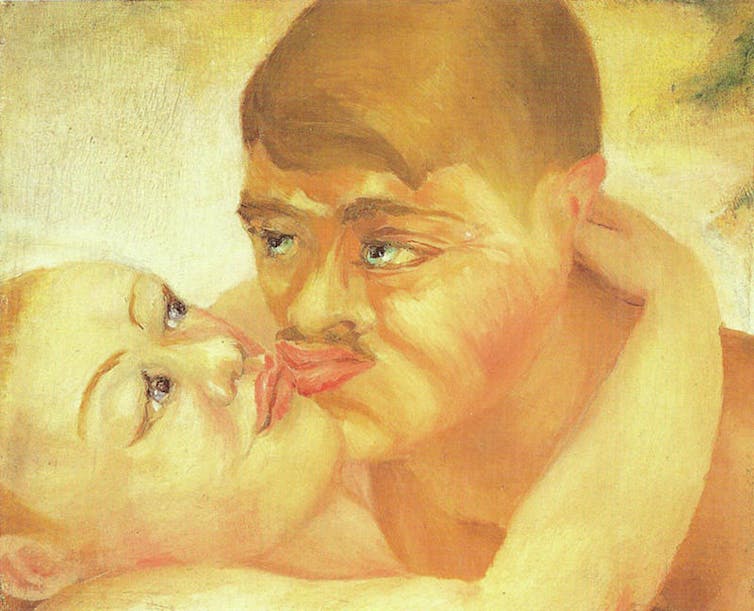

Like his most famous novels, Lady Chatterley’s Lover and The Rainbow, the paintings provoked censorship and police prosecution – there are a lot of body parts. Lawrence’s human figures are either dwarfed in huge, desolate landscapes, or enclosed into the frame in a press of nude bodies. Though the paintings are not that good, technically speaking, they are strangely absorbing, especially in their rendering of the body, so delicate and grotesque and immediate.

It’s that aspect of Lawrence which might be the most compelling for us, now: his awareness of the simultaneous vulnerability and power of the flesh.

Feigel’s project to invigorate literary criticism with the personal is admirable, but I was not fully gripped by her memoir. I can understand her wish to preserve privacy for herself and her children, but her accounts of love affairs, divorce, custody disputes, even friendship, lack the meaty, overpowering sense of revelation Lawrence worked so hard to achieve.

Less convincing also is Lawrence as a guide to contemporary living. Lawrence on sex? Maybe, though really only if you’re heterosexual. Lawrence on community? He definitely had theories about how to live with others in ways that counteracted the alienating effects of modernity, but he seems to have been kind of a jerk to the people he actually lived with.

But Lawrence, the anti-democrat, on politics? Lawrence on climate change? Technophobia and nature worship can’t fix fossil fuel dependence, and refusing to participate in political action won’t save us from 21st century despotism.

Lawrence’s dread of mechanical civilisation might be relatable and nostalgic on those days when we worry our kids are having too much screen-time. But we need to remember that advanced scientific knowledge and technological infrastructure have also enabled the rapid development of life-saving COVID vaccines. Lawrence is, as Feigel often admits, an unreliable prophet.

The two exclamation points in its title, borrowed from Lawrence’s 1917 book of poems, suggest urgency, even vanguardism. The book has appeared later than other recent attempts to revive Lawrence: Cusk’s Second Place and Frances Wilson’s biography Burning Man (2021). Though the genre-bending between memoir and literary criticism is an interesting experiment, Look! We Have Come Through! is ultimately not as satisfying as these earlier books. Its publication feels belated for a book that is, in part, about how to live through the extremity of COVID.

Feigel is a sensitive critic, sympathetic to Lawrence’s style and the substance of his novels. She makes a generous case for what his prose makes possible. I’m not sure I would ever want to live with Lorenzo, but I might let him stay for a very short visit.