Joko Widodo, popularly known as “Jokowi”, has served as Indonesia’s president for almost a decade. He is hugely popular, garnering around 80% in some polls. But the constitution bars him from serving a third term in office.

Repeated proposals in recent years years to amend the constitution to allow Jokowi to run again have gained little public or political traction. This leaves him unable to contest the next presidential election in February.

Key powerbrokers, however, have been keen to make the most of the tens of millions of votes that Jokowi commands – and maintain his inner circle’s influence after he leaves the palace next year.

Perhaps their most conspicuous strategy to do this has been to install Jokowi’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as vice presidential running mate for Prabowo Subianto, now ahead in the polls with a huge lead of 20 points.

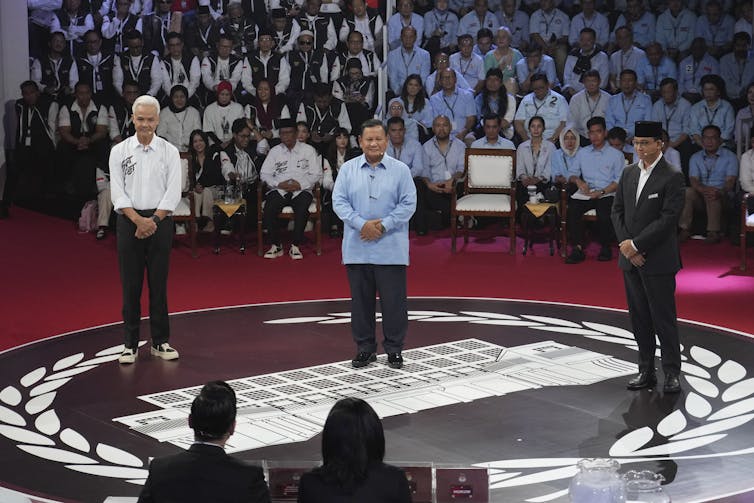

The professor, the general and the populist: meet the three candidates running for president in Indonesia

Concerning legal moves

Getting Gibran into that position required the co-option of one of Indonesia’s most respected judicial institutions – the Constitutional Court.

The main roadblock for Gibran (and Jokowi) was that the election law imposed a minimum age of 40 for presidential and vice-presidential candidates.

In a case challenging that age limit, Chief Justice Anwar Usman, Jokowi’s brother-in-law and Gibran’s uncle, intervened to ensure a majority of judges would reverse the court’s position in three previous decisions.

As a result, the election law was altered to permit younger candidates to stand if they had previously held office as head of a sub-national government. Gibran, 36, just happens to have served as mayor of Solo in central Java, a job his father once held, and so the decision meant he could now run for vice president.

The decision has trashed of the reputation of the Constitutional Court, raising questions about its continuing credibility and future, with witty hackers changing its name on Google Maps to the “family court”.

However, not all judges agreed with the decision. Three judges dissented, with some raising questions about Anwar’s behaviour and his obvious conflict of interest. Public outrage over the decision led to the court’s ethics tribunal removing him from his position as chief justice last month.

A twist in Indonesia’s presidential election does not bode well for the country’s fragile democracy

Yet, Anwar remains one of the nine judges on the court, the decision he is accused of “fixing” stands, and Gibran’s nomination as a vice presidential candidate can probably not be reversed.

Worse, the national legislature has been debating amendments to the Constitutional Court statute that could enable the removal of the dissenting judges. Ironically, this might be through the imposition of a minimum age requirement on Constitutional Court judges. One of the court’s most respected judges, Saldi Isra, is under the proposed age, and appears to be a target.

Mast Irham/EPA

Jokowi picks a side

From the outside, it may seem like Gibran and Prabowo are strange bedfellows. Prabowo is a former son-in-law of the dictatorial former president Soeharto. He is a cashiered former general who has long been accused of serious human rights abuses, including alleged killings in East Timor, Papua and even the capital, Jakarta.

Prabowo has never faced trial, although several of his men were tried and convicted. He has denied the allegations against him.

Ironically, he was also Jokowi’s bitter opponent in the past two elections, which polarised Indonesia. Prabowo’s refusal to accept his electoral defeats in 2014 and 2019 led to dramatic challenges in the Constitutional Court.

Indonesia’s presidential election dispute: Prabowo’s plan to challenge election result may be in vain

But the enmity between Jokowi and Prabowo seemed to evaporate almost immediately after the court challenges failed, with Prabowo pragmatically accepting the job of defence minister in Jokowi’s cabinet.

Now, Jokowi appears to have decided that Prabowo, of all people, offers the best chance to build a dynasty to keep some sort of hold on power. Certainly few see Gibran – largely silent or inarticulate in public appearances – as serious leadership material. He is widely assumed to be a proxy for Jokowi.

This dynasty-building exercise has involved a massive and expensive campaign that many complain has co-opted government agencies and programs to promote Prabowo and Gibran.

It has also involved reinventing Prabowo, a one-time special forces general, as a gemoy (cute) grandpa, with viral video clips showing him dancing and playing with kittens.

Jokowi’s alignment with Prabowo (through his son) is all the more surprising given Jokowi was a longtime member of PDI-P (Indonesian Democracy Party – Struggle). PDI-P is Indonesia’s largest political party. It twice successfully nominated Jokowi for the presidency, and it has its own candidate, Ganjar Pranowo, in February’s election. Party rules require Jokowi to support him.

By abandoning Ganjar for Prabowo (who has his own party, Gerindra), Jokowi will effectively be stealing votes from PDI-P and declaring war on its boss, the formidable – and vengeful – former president, Megawati Soekarnoputeri, the daughter of Indonesia’s first president. She will fight hard to maintain her party’s power and influence.

Tatan Syuflana/AP

Is Indonesia’s democracy under threat?

Despite the political chaos these moves have sparked, Jokowi’s bet that his loyalists and the general public don’t really care about constitutional crises or claims of dynasty building seems to be paying off.

Of course, votes could still shift in the next month and a half. However, there is a sense the momentum created by Jokowi’s support for Prabowo may make his victory inevitable. Some former critics are already quietly changing sides to ensure a share of the spoils.

Jokowi has previously said “our democracy has gone too far”. And Prabowo has openly called for a return to the model of Suharto’s authoritarian New Order.

So, a Prabowo-Gibran victory may be good news for the elites now in power, but it will likely be bad news for Indonesian democracy. It will confirm – and probably accelerate – the regression that most observers, including Freedom House, agree is already advanced under Jokowi.

Many voters seem untroubled by this. Indonesia’s post-Soeharto “Reformasi” wave of democratisation is mere history for Indonesia’s Gen Z, who appear to have limited interest in all that was achieved two decades ago and no experience of living under authoritarianism.

But the activist legal NGOs that form Indonesia’s policy “brains trust” are depressed and anxious. Certainly, some are protesting, and a few are even challenging the court decision that allowed Gibran to run.

However, many are intimidated by criminal charges that members of Jokowi’s administration have brought against critics with increasing frequency in recent years. From the perspective of civil society, Jokowi’s strategists seem to have a fix in place and dark and difficult times lie ahead.