Baghdad native and former architect Ghaith Abdul-Ahad traces his start as a journalist to the day Saddam Hussein’s statue was toppled in central Baghdad, on April 9 2003 – two weeks after US troops invaded the city.

Framed as a watershed moment, Western media coverage at the time “heavily implied” the statue was taken down by “a large crowd of cheering Iraqis”.

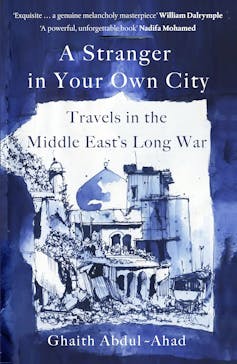

Review: A Stranger in Your Own City: Travels in the Middle East’s Long War – Ghaith Abdul-Ahad (Hutchinson Heinemann)

But Abdul-Ahad, who was standing in the Green Zone in Baghdad, “along with a few other Iraqis and a much larger crowd of foreign journalists”, remembers watching an armoured vehicle with a large crane on it reverse into the square.

“Oh no, don’t do it,” he thought. “Let the Iraqis at least topple the statue of their dictator.”

Climbing to the top of the monument, a US marine secured a length of thick rope around its neck, and “with all the arrogance of every occupying soldier throughout history”, covered the statue’s face with an American flag.

Jerome Delay/AP

Abdul-Ahad reflects on the image of a handful of Iraqi men defacing Hussein’s toppled monument with glee and rage: “That iconic image has played again and again on every report on Iraq ever since, as if those men represented all the nation.”

Indeed, images and stories that reduced the Iraqi population to a monolith (and epitomised Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism) were rife in Western media coverage at the time. They helped manufacture consent for the indiscriminate violence of the occupation.

But expressions of gratitude for the American goal of “restoring democracy” were not unanimous. Describing the moment US troops massacred a crowd of unarmed civilians on Haifa Street in 2004, Abdul-Ahad – who was on the scene and wrote about it for the Guardian – recalls being pulled aside by a man who noticed a camera in his hands:

‘Take pictures!’ he told me. ‘Show the world American democracy.’

Orientalism: Edward Said’s groundbreaking book explained

Beyond ‘shock and awe’

On March 20 2023, the 20-year anniversary of the Iraq War, media outlets around the world published op-eds lamenting the US-led coalition’s “mistakes” in Iraq.

In the two decades since the brutal invasion, its architects have held onto near-total impunity. Iraqis attempting to pursue justice through lawsuits and criminal trials have faced countless obstacles. And in 2019, the UK government even sought to grant amnesty to troops who committed war crimes during their deployment.

Countless memoirs from US and UK veterans published over the past two decades betray persisting delusions of heroism. Historians and journalists, too, continue to pore over the justifications and motives behind the war.

A Stranger in Your Own City, a “de-centering of the West in the history and contemporary situation of the region”, is a standout in this saturated field.

Although published to coincide with the anniversary of Iraq’s invasion, this captivating debut broadens its scope beyond the US bombardment campaign of “shock and awe”.

Sweeping and dynamic

A Stranger in Your Own City is sweeping in scope. It doesn’t fit neatly into any one genre, but reads at once like a travelogue, geo-biography, memoir and political history.

Its chapters shift between personal vignettes from Abdul-Ahad’s life – encounters with doctors, old friends, schoolteachers, militia leaders and jihadist fighters – and sections that provide an overview of Iraqi political groups and historical events.

But this dynamic collection rarely meanders, nor does it lose the reader in its frequent shifts in focus. Instead, its structure foregrounds what the book does best: unsettling the enduring myths about the origins of Iraq’s never-ending crisis.

Context for the emergence of sectarian tensions, corruption and religious extremism in Iraq are but a few of the gaps in common knowledge filled.

A Stranger in Your Own City spans almost 40 years, following the contours of Iraq’s modern political chronology. It takes us through the 1980–88 Iran–Iraq War, to the mass demonstrations against the corruption and “misrule of the (post-invasion) sectarian parties” that broke out across Iraq in October 2019.

Abdul-Ahad traces the various centres of power and wealth since the 1980s, from Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime to the emergence of the Islamic State in Mosul, which became the largest population centre under ISIS control after it was occupied by Islamic State forces in June 2014.

He reveals a bleak historical throughline: “a concentration of unaccountable power, shadowy intelligence services and corruption.”

Those in power in Iraq framed their corruption under various guises of nationalism, sectarianism and religiosity. But they served only to deepen the inequalities that had emerged under Saddam Hussein’s rule.

‘We did it so badly … it’s now backfired’: women and minority US forces reflect on the invasion of Iraq – now 20 years ago

Sectarian tensions heightened by occupation

In the preface, Abdul-Ahad describes his nocturnal hypervigilance while hiding out in a hotel room in Baghdad in 2007, “listening to the sounds of a city at war”.

He scans an old photo of his friends from high school, trying to infer what sect they belong to. The exercise seems absurd to him: information that was once all but irrelevant is now a primary organising principle of Iraqi society.

He echoes this bleak contrast between pre- and post-invasion Iraq in a chapter called “The Wedding”. We meet Akram and Zainab, an intersectarian couple planning their wedding in Baghdad. Their matrimony, which would once have been “the most common and normal thing”, became a dangerous and tenuous prospect during the 2006 civil war. It was an act, Abdul-Ahad contends, that was now considered “akin to treason”.

Here, Abdul-Ahad challenges the widely held view that sectarian tensions were an entrenched and longstanding source of conflict in Iraq before 2003. We learn instead that sectarianism was, in fact, catalysed by the US occupation – namely in the formation of the post-Saddam government.

Mohammed Jalil/EPA

The US Coalition Provisional Authority (the governing body of the occupation) selected a group of Iraqi elites and exiled politicians, many of whom had fled Iraq decades before during Ba’athist rule, to form “the charade called the Iraqi Governing council”. Initially, it was an empty symbolic expression of power, while the Coalition Provisional Authority continued to exercise colonial control.

The council organised itself according to a model of confessionalism known as the “muhassasa” system. The 25 members ostensibly represented different sects and ethnic groups in Iraq.

But this arrangement didn’t reflect the lived realities of their constituents, and only provided another opportunity to establish corrupt patronage networks.

Ultimately, these networks functioned as “personal fiefdoms” that distributed and privatised resources and services following sectarian quotas. And, as Abdul-Ahad argues, the rearranging of Iraqi society across sectarian lines – both socially and geographically – fuelled the civil wars to come.

An extension of America’s war

Abdul-Ahad challenges the binary view of Iraqi societal tensions as split neatly between Sunni and Shia Muslims following the 2006 civil war. The US occupiers, he writes, “like all conquerors aimed to simplify their occupation of a society by breaking it into components”.

He examines a “wide range of localised schisms and fault lines, feuds based on class or geography”. We read of the various groups that were established, and their rapid and at times incomprehensible shifts in allegiance and goals.

Despite this ever-changing political climate, Abdul-Ahad contends, “as for the Iraqis, friend and foe alike, this was still an extension of America’s war, even if it was now only Iraqis who were butchering Iraqis”.

Indeed, the US invasion of Iraq wasn’t simply a misguided attempt to liberate a nation held hostage by an autocratic leader. Instead, it was a protracted, deliberate campaign of political and economic destabilisation.

Abdul-Ahad points out that “western pontificates” limited their critiques of the invasion to what a 2005 New York Times article called “dangerous incompetence”. He responds: “No amount of planning could have turned an illegal occupation into a liberation.”

Now, 20 years on, notions of failure and incompetence still pervade media responses to the war on Iraq.

In March, Jeremy Bowen called the invasion “a failure not just of intelligence but of leadership”. Former Bush speechwriter David Frum (of “Axis of Evil” infamy) put it in egregiously dismissive terms: “[The Bush administration] were shocked and dazed by 9/11. They deluded themselves.”

While most are hard-pressed to view the invasion of Iraq as anything but catastrophic, the myth of the occupation’s “failure” persists.

Iraq war, 20 years on: how the world failed Iraq and created a less peaceful, democratic and prosperous state

Disaster capitalism in Iraq

By vaguely attributing the occupation to the “desire to project American power in a unipolar world”, I sometimes wondered whether the book should have delved more deeply into the ways Iraq’s destabilisation served the interests of US imperialists – and the corporations that profited off its demise.

I felt some important political context was missing. And where we can’t infer a clear line of reasoning for the US-led invasion, the “failure” narrative threatens to re-emerge.

For instance, there is no mention that privatisation of Iraqi oil was high on the US agenda following the invasion. Multinationals seized virtually the entire Iraqi oil sector, which had been nationalised in 1972, with “production-sharing agreements” by 2009.

Abdul-Ahad illustrates how the Gulf War and 13 years of crippling sanctions “brought [Iraq] to its knees”. But there’s little reflection on what these punitive measures achieved for the interests of their primary perpetrator: the US.

US Coalition Provisional Authority leader L. Paul Bremer is sketched out in a short chapter, aptly called “The Viceroy”. It describes his “De-Ba’athification”: a far-reaching gutting of the public sector.

Roughly 85,000 public service workers were fired outright due to nominal affiliations with the Ba’ath party – even though registration with the party was mandatory for all who held public jobs. But what is missing from this chapter is a more substantial analysis of what these policies did.

Stefan Kaklin/Pool/EPA

Iraq’s reconstruction and governance were largely outsourced to private companies and military contractors, who sought to profit off the sudden political destabilisation.

This constitutes part of a broader system of state-(un)building, which Naomi Klein has termed “disaster capitalism”.

Disaster capitalists exploit and even manufacture political and economic crises so they can introduce vastly transformative neoliberal policies amid the chaos. Corporations can then swoop in and clean up profits in the wake of the destruction.

In this context, the invasion of Iraq was anything but a failure in the eyes of its architects.

Why you can’t explain the Iraq War without mentioning oil

A productive tension

As I write this review, I’m reminded the representational responsibilities of a book like this aren’t set in stone. And considering the motivations for the US-led invasion is not its priority. Abdul-Ahad very deliberately resists buying into a reductive narrative about what caused the war – and rightly so.

The stories that fill this book bolster it with a plurality of perspectives. A productive tension emerges between Abdul-Ahad’s personal understanding of Iraqi society and politics and those of his interviewees, complicating the Western media’s monolithic rendering of Iraqis.

At moments, the author seems to succumb to generalisations about national or sectarian attitudes. But then he pulls back to reflect on the limitations of his thinking.

In a later chapter, Abdul-Ahad asks a fellow journalist, Omar al-Shahir, why Sunni groups demonstrating in Ramadi against the sectarian violence of the Maliki administration couldn’t establish a more unified leadership.

Shahir responds: there was no Sunni unity to begin with. Abdul-Ahad proceeds to admit, “I was committing the same mistake as those committed by the people in the Dignity camp: addressing all the Sunnis as if they were one homogeneous people.” In these moments, the hybrid structure of the book shines.

Ali Abbas/EPA

It’s also important to note that many writers from the Global South face implicit pressure to humanise themselves and their “people” for Western audiences.

They are called on to produce “human stories” that invite compassion and sympathy. But this pressure risks depoliticising their experiences – and relegating their historical and political contexts to the narrative margins.

‘Deeply human’, but still political

A Stranger in Your Own City has been praised for its “deeply human reporting”. But Abdul-Ahad mostly avoids this trap, without sacrificing either personal resonance or political subjectivity.

A Stranger in Your Own City is often difficult to read. Graphic descriptions of torture, loss, despair and rage pervade its pages. The book ends with the Tishreen Movement protests of 2019. There, young Iraqis took to the streets, united in their struggle against “the corruption and nepotism of the ruling kleptocracy of religious parties”.

While the protests failed to inspire substantial political change, the reverberations of a “larger more common identity” were felt.

In the wake of the Tishreen Movement, Abdul-Ahad renders an image of ambivalent, angry steadfastness and hope. He concludes: “the failure of the ruling class, the religious parties, regional bosses, the clergy and militias to heed the warnings of Tishreen will lead to their eventual demise.”