Indonesians are going to the polls to elect a new president on Wednesday. There are three candidates running, alongside their vice presidential candidates.

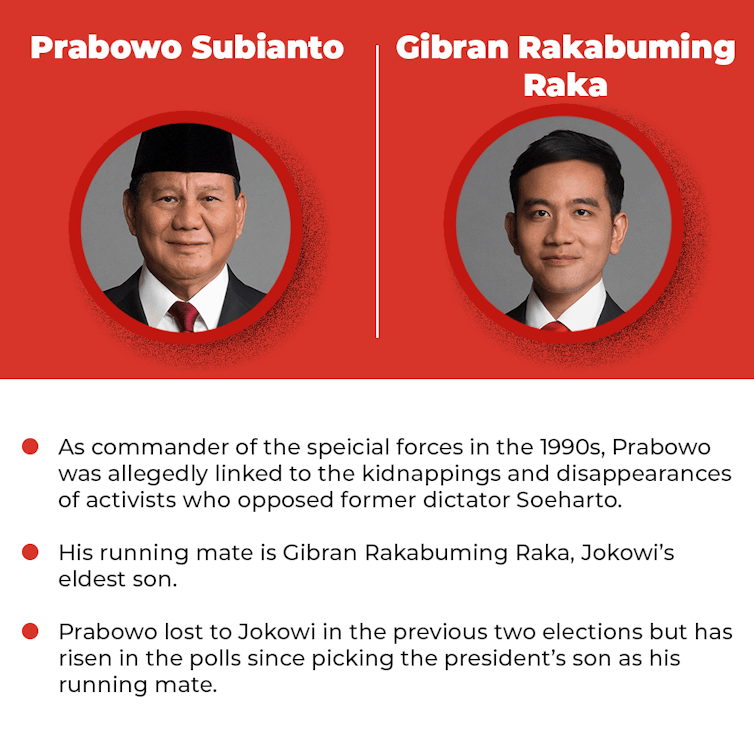

According to opinion polls, the favourite is Prabowo Subianto, leader of the Greater Indonesia Party (Gerindra), a populist and nationalist party he founded in 2008. A former army general, Prabowo has already stood unsuccessfully for president twice before. He is also the defence minister in the cabinet of the current president, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

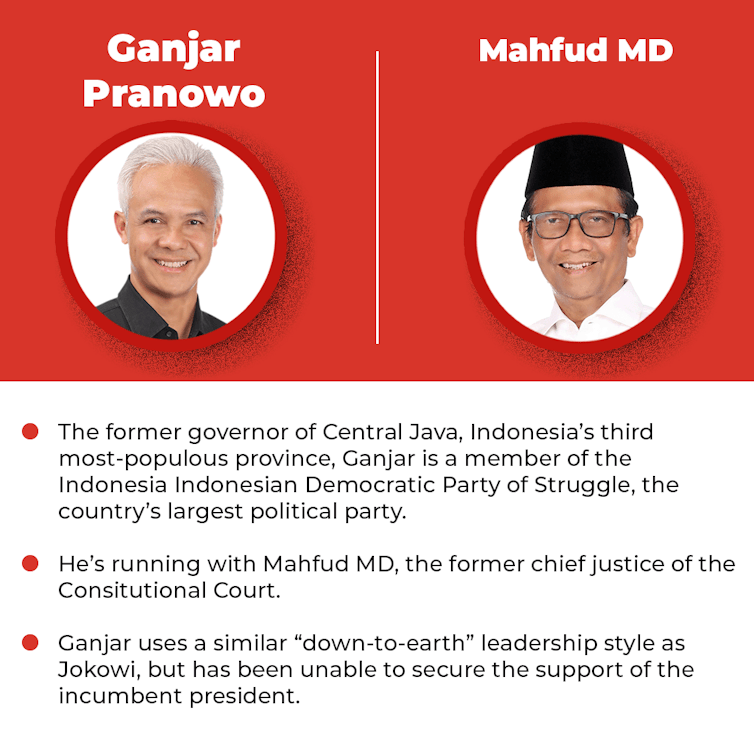

The other contenders are Ganjar Pranowo, a former governor of the large province of Central Java and a member of Indonesia’s biggest party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), and Anies Basweden, an independent candidate who was governor of the city of Jakarta.

Prabowo is the frontrunner, but it’s unclear whether he will win an absolute majority of votes in the first round. If he fails to win 50.1% of the vote, there will be a runoff election between the two leading candidates in June.

The Conversation, CC BY-SA

The Conversation, CC BY-SA

The Conversation, CC BY-SA

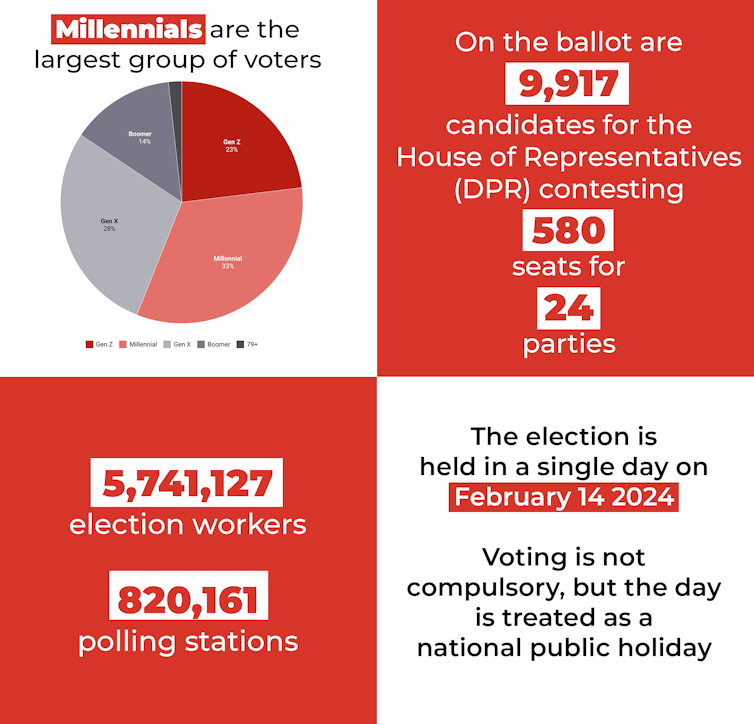

By the numbers

Voters are also casting votes in parliamentary elections, which include:

580 seats in the House of Representatives (DPR), with more than 9,900 candidates

152 seats in the Regional Representative Council (DPD), designed to represent the regions, with around 670 candidates

and local parliaments in each of the 38 provinces and 416 districts.

In total, there are over 2,700 separate electoral contests being held for around 20,500 seats. All are the responsibility of Indonesia’s independent election commission (the Komisi Pemilihan Umum, or simply KPU) to administer impartially and efficiently.

The Conversation, KPU, Perludem, CC BY-SA

Logistical nightmare

Indonesia is the world’s third-largest democracy after India and the United States – and all three are holding elections this year. But since Indonesia is holding five separate polls on one day, it is often touted as the largest and most complex single-day election in the world.

Indonesia is an archipelago with about 6,000 inhabited islands, some of them remote and with limited infrastructure. The distance from Aceh in the west to Papua in the east is some 5,100 kilometres (3,200 miles), wider than the continental US.

Cute grandpa or authoritarian in waiting: who is Prabowo Subianto, the favourite to win Indonesia’s presidential election?

It is a massive undertaking to organise an election of this size, from procuring polling station equipment to managing a huge election staff to ensuring the public trusts the integrity and fairness of the vote. The election commission does a remarkable job making sure the vote happens on time and the ballot counting occurs quickly and without tampering.

To get an idea of the size of the task facing the KPU, let’s look at the presidential election first.

There are 204 million registered voters in Indonesia, so the KPU has to print and distribute this many ballots across the country for the presidential vote alone, with a few million extra in case polling stations run short.

The commission is then required to deliver, count and return the ballots to over 820,000 domestic polling stations, in addition to more than 3,000 stations overseas. Since there may be a second-round, runoff election, the KPU must be ready to repeat the whole exercise in a few months. This time it would need a different set of ballot papers showing the two final candidates.

But things get really complicated when it comes to the contests for Indonesia’s various national and regional parliaments, even though these get relatively little attention compared to the presidential poll.

The presidential election involves a simple majority count of three candidates. But the national and regional parliaments are conducted through a proportional representation system, the same used in countries like Germany and New Zealand, and for the Australian Senate. Under this system, parties win seats in proportion to the votes they receive. For example, a party winning 20% of the votes will take up around 20% of the seats in the chamber.

Adding to the complexity, voters in Indonesia are not compelled to vote just for a party, but can choose an individual candidate within a party’s list. So, when voters arrive at the polling station, they are presented with a huge ballot paper for the national parliament alone, which lists, on average, 118 candidates.

And they must also make choices for three other chambers – in addition to the presidential vote.

An unglamorous, but remarkable democratic achievement

So, how well has Indonesia done in this massive task of making democratic elections work?

After languishing under a dictatorship and rigged elections for four decades under the rule of Soeharto, the country has done remarkably well since embracing democracy in the late 1990s.

In fact, Indonesia rarely receives recognition for this transformation. In a world where democracy seems increasingly under pressure, Indonesia has managed five peaceful and democratic transfers of power. In comparison to neighbouring states in Southeast Asia, where one-party dominance is widespread or democratic progress has been crushed under military coups, Indonesia stands out as a bastion of democratic politics.

Dedi Sinuhaji/EPA

None of this is to say that Indonesia’s system is flawless. In fact, domestic and international observers have increasingly noted the reemergence of authoritarian instincts among the country’s leaders and the rise of dynastic politics in which incumbents engineer the elections of family members.

And this not only applies to prominent figures from the Soeharto days, such as the leading presidential contender Prabowo. Jokowi has also been accused of paving the way for a political dynasty by using his son’s candidacy to ensure he’ll have influence in a Prabowo presidential administration.

But when it comes to the electoral contest itself, Indonesia’s election commission, while not perfect, has delivered reliable and trustworthy outcomes.

The administration of free and fair elections is an unglamorous job, but it is crucial for maintaining public trust in the political system. It also ensures that candidates and parties accept the results and are not tempted to launch coups or deliberately obstruct the post-election process.

Given the strains placed on the United States’ long-established democracy in recent years, Indonesia’s achievement in making elections work should not go unnoticed.

Even with a 30% quota in place, Indonesian women face an uphill battle running for office