In September last year, several leading scientists were effectively banned from further research in Indonesia’s vast tropical forests, where most had been working for decades.

Their sin? In large part, producing research suggesting the Bornean orangutan was in trouble – and following it up with an opinion piece which countered the government’s assertion the species was rebounding.

These researchers clearly angered someone powerful. Soon, the influential environment and forestry ministry circulated a letter accusing the scientists of writing with “negative intentions” that could “discredit” the government. They were to be barred from the forests.

My colleagues and I have published new research exploring the risks of this response from Indonesia’s government.

Shutterstock

Worrying — and surprising

Indonesia’s reaction is a worrying sign. The island nation has a fast-growing population and economy, as well as spectacular biodiversity and one of the world’s largest areas of tropical forests. But its growing population and economy have been putting pressure on the natural world for decades.

Indonesia’s combativeness is also surprising. In recent years, forest destruction has declined by two-thirds, following government clamp-downs on illegal logging, forest burning and felling for plantations. This is a remarkable achievement.

Research reveals shocking detail on how Australia’s environmental scientists are being silenced

So why the recent crackdown on the researchers? It’s likely to be precisely because Indonesia has been doing better environmentally. Its leaders want their progress to be recognised, not criticised.

But while it’s important scientists are fair – and do recognise welcome progress when it happens – it’s even more important governments let scientists do their work, even if the results we report are not what they want to hear.

This isn’t the first time Indonesia has tried to silence environmental scientists. Three years ago, researcher David Gaveau was deported from Indonesia after publishing estimates of wildfire extent much larger than those reported by the government.

For local and overseas researchers in Indonesia, the pressure is clear. Many privately say to us and other colleagues that they feel coerced to publish good news, or at least avoid bad news.

Governments must be open to warranted criticism

Conservationists and researchers have long run up against suppression or even violence in developing nations with large forest tracts, such as Brazil, Colombia, the Philippines and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

That’s because there’s huge pressure on these forests. Demand for economic development often leads to exploitation of remaining forests.

While Indonesia’s forest management is improving in some ways with deforestation clampdowns, there are still very real areas of concern.

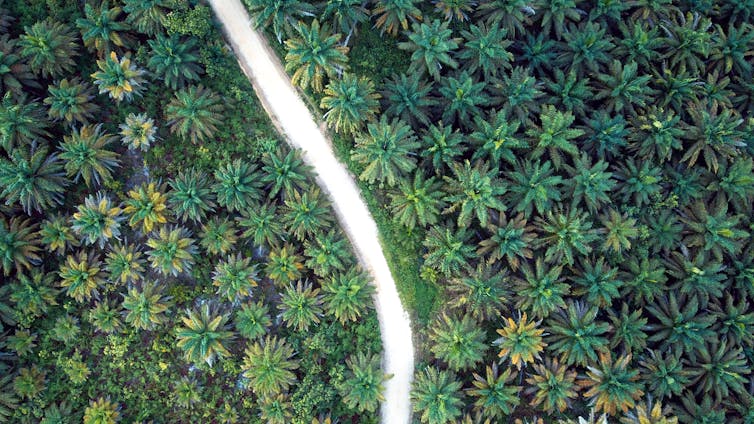

In recent decades, huge swathes of forest have been felled and converted into palm oil and wood-pulp plantations. The rush for critical minerals underpinning the green transition, such as nickel, are damaging fisheries and rivers.

And then there are the roads, which are expanding dramatically across Indonesia. A road is a spike driven into the natural world. Once a road is in place, the forest opens up like a flayed fish. Bulldozers, chainsaws and mining equipment can come in. It’s a devastating dynamic.

Shutterstock

Alternative data: setting the record straight on the scale of Indonesia’s 2019 fires

In the past few decades, Indonesia has been plagued by environmental catastrophes, from massive forest loss to lethal smoke plumes from vegetation burning.

To avoid being blindsided by future environmental catastrophes, Indonesia needs a dynamic and open scientific community – one that isn’t being pressured to toe the government’s line.

How Indonesia’s election puts global biodiversity at stake with an impending war on palm oil