There is something familiar about Aunty June, the protagonist of Julie Janson’s Madukka the River Serpent.

Like Precious Ramotswe in Alexander McCall Smith’s No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, she opens her own investigation agency. Like Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, Aunty June is underestimated by powerful men. Like Vera Stanhope from the Ann Cleaves novels and BBC series, she doesn’t give up until the truth comes out.

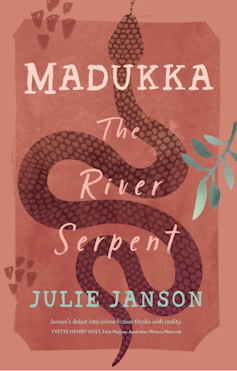

But any resemblances between Madukka the River Serpent and the works of these British authors ends there. In this self-described “Indigenous crime novel”, Darug playwright, poet and novelist Julie Janson draws attention to the genre’s limitations to provide justice for the systemic violence experienced by Indigenous peoples.

Review: Madukka the River Serpent – Julie Janson (UWAP).

The novel is set in 2020 in the fictitious northern New South Wales town of Wilga, on the Darling River. Like in much “outback” noir, Wilga is no idyllic country town, but the divisions and tensions within the town are more obvious than we see in many such novels. There are constant scrapes between farmers, the police, environmentalists, white supremacists, First Nations peoples and motorcycle gang members.

These tensions are heightened by the environmental disaster engulfing the town. The impact of climate change, exacerbated by the extractive practices of “Big Cotton”, has drained the river and waterways that sustain life. This in turn threatens the Dreamings that keep culture alive. “Totems die, then we die,” says one Murri man.

A host of crimes

The mystery centres on the disappearance of Thommo, a Murri “ecological hero”. The gungie (police) led by Sargent Blackett refuse to take his disappearance seriously. But when Aunty June is visited by Thommo’s unsettled spirit she decides to investigate.

Aunty June is a “fifty-year-old […] freshwater Gamilaraay Aboriginal woman born of clay plains, dust and kangaroos”. Though she has relatives in town and is a respected Elder, she is not a Traditional Owner. June is supported by her brother William, sister-in-law Merle, and her feisty and uncompromising teenage niece Arana.

Aunty June’s enquiries quickly move beyond the disappearance and death of an individual Aboriginal man. Without ever losing sight of Thommo’s tragedy, the investigation explores a host of other crimes. These include dispossession, theft, corruption, endemic racism, Black deaths in custody, sexual violence, human-induced climate change and the destruction caused by industrial-scale farming, among other acts of physical and symbolic violence.

The wide range of violence and crimes is a heavy load for any novel to bear and Madukka the River Serpent doesn’t always carry them well. But where many a novel would treat each individual act of violence discretely, Janson traces the connections between them. The problems facing the Murri people here – and First Nations everywhere in the country – cannot be resolved by treating each one in turn. They are all intertwined, interconnected.

They also have a long history. The first chapter, titled “26 January: Survival Day”, frames the present, giving it meaning. Police and farmer aggression towards Wilga’s Indigenous population in 2020 is presented as the latest manifestation of a history of violence dating back to the Waterloo Creek Massacre of 1838.

Friday essay: ‘killed by Natives’. The stories – and violent reprisals – behind some of Australia’s settler memorials

Connection to Country

While the novel rightly offers an unflinching depiction of Aboriginal dispossession, it is not stuck in the past. It is also concerned with the future. Aunty June and others want to break the historical cycle of violence that has plagued Indigenous-settler relations.

The hope for a better future is also tied up in the novel’s depictions of Country. Connection to Country is central to Aboriginal culture. Wilga’s First Nations are “river people” and the

Darling was their lifeline along its winding path. Rivers of stars in the Milky Way, the whispered Madukka and paths to follow Dreaming stories. Connected like a spider web to every living thing.

The wanton destruction of the environment for economic gain “dries the Dreaming tracks out”, spelling “genocide for our spirit”.

Yet it is not only the First Nations characters who suffer from water theft by big irrigators; it is all people, “Black and white”, especially the three million people for whom the Darling is a water source.

In framing concern for Country as an environmental necessity, Madukka the River Serpent tries to overcome past divisions and bring together “Black, white, Asian, gay, straight, trans, greenies, ferals, feminists, Labor Party, Shooters, Independents and even the National Party” in a common cause.

Given the debate over the referendum on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to parliament, this is a tall ask.

An ambitious and confronting crime novel, Madukka the River Serpent is most convincing at reminding readers that “White Australia has a black history” of violence against First Nations people. It is less successful, however, at fostering the shared sense of community that Aunty June sees as central to addressing the environmental catastrophe that affects us all; though to be fair, this is a task beyond the ability of any single novel.

It is surprising there is not more Indigenous crime fiction. The genre’s place-specific exploration of crime and justice seems ideally suited to Indigenous authors wanting to reach and inform a broad audience of historical and contemporary systemic injustice.

After initial forays into the genre from the 1980s by some Indigenous writers, Kamilaroi author Philip McLaren published his first crime novel, Scream Black Murder, in 1995. Murri writer Nicole Watson wrote The Boundary in 2011 and Goorie author Melissa Lucashenko won the Miles Franklin Award for her 2018 novel, Too Much Lip.

Indigenous novelists like McLaren, Watson, Lucashenko and Janson are casting crime fiction in Australia in a new light. They remind readers that Australia’s greatest fiction is terra nullius, the belief that this country was uninhabited prior to European settlement, and that its greatest crime is the ongoing violence and dispossession of its First Nations people.

How crime fiction went global, embracing themes from decolonisation to climate change