The Australian Women’s Weekly, the first Australian magazine dedicated solely to the interests of women, turned 90 this year. The magazine is known for its coverage centred around the home and child-rearing, but the early editions of the Weekly also created a space for Australian women to engage with politics through the lens of womanhood.

Since its first edition in June 1933, the Weekly has provided Australian women with a forum to learn, discuss and debate a range of issues. Its coverage throughout the 1930s reveals how the magazine negotiated the tension between conservative and progressive viewpoints on women’s involvement in political affairs.

The Weekly and the 1930s

The magazine’s first editor, George Warnecke, developed a prototype for a publication tailored to female readers after studying women’s interests. He wanted it to be “distinctly Australian [and] appeal across age groups”.

The Weekly was immediately popular. The initial estimated print run of 50,000 copies increased to 121,162 copies. By the end of 1939, the Weekly had a circulation of 445,000.

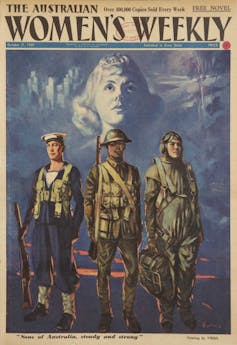

Originally launched as a “forty-four-page black and white newspaper”, it sold for two pence and followed traditional newspaper formatting, printed in broadsheet columns. It appealed to female readers with engaging images of womanhood – the first issue’s cover story was on Sydney women’s fashion.

However, the paper quickly moved away from this format towards a cover centred on a single evocative image. This change can be seen throughout August and September 1933, when the images on the front cover became increasingly prominent. Eventually, they took over the whole page.

Inside, the paper covered fashion, beauty, homemaking, entertainment – and current affairs. The first edition’s other cover story reported on a recent conference of the Women Voters’ Federation in Adelaide under the headline “Equal Social Rights for SEXES”.

In early issues, political topics were primarily addressed in the “Points of View” column on the editorial page, which acted as a forum for the editorial team to provide short critical commentaries on issues they deemed important to Australian women.

This space included readers’ responses. Another dedicated column, “So They Say”, provided space for readers to discuss previous articles, current affairs and social issues.

Bilby, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Politics and the home

The Weekly’s coverage and reader contributions on current affairs created a platform for women to dissect political topics. But it balanced the tension between conservative and progressive viewpoints on women’s involvement in politics to cater to their commercial audience.

In a March 1934 editorial, Warnecke declared “this paper knows no politics” and “most women are not specially politically minded”. Women’s sphere of influence, he argued, was the household.

But Warnecke implied that women could still influence society and culture. They were outside formal institutions, but could shape the nation politically in other ways: “public opinion starts off as private opinion, and this is formed in the home”.

The editorial suggested that the Weekly’s coverage was not “non-political”, as one reader, Miss Clarke, interpreted. Rather, the paper managed to establish a forum for both conservative and progressive ideological viewpoints by claiming to separate the social from the political.

An example of this can be seen in the editorial “Women and Democracy”, published on July 14 1934, which showcased the political influence women held over their families:

The fact is that, though [women] may not take a public part in politics, the Australian woman exercises a potent influence at election times, not only because of her voting power, but because of the high esteem in which her opinion is held by the male members of her household.

Warnecke also defended women’s right to vote: “there has never been any serious question of the Australian woman being in an ‘inferior’ position because of her sex”, he argued.

How the Australian Women’s Weekly spoke to ’50s housewives about the Cold War

Australian women’s political interest

Although the Weekly often framed political debate through social and cultural lenses, there was still ample traditional political reportage in early editions. This is evident in feature articles, occasional columns and reader contributions that asserted the importance of women’s engagement with political institutions.

Mrs V. Cantwell’s October 1933 contribution positioned her against a fellow reader, identified by the initials A.S., who had declared that women were not interested in politics. Cantwell retorted:

The improved conditions of women and children to-day, as regards social services, general health, etc., are directly attributable to the fact that women are taking an increased and creditable interest in public affairs.

Cantwell’s contribution illustrated the progressive view of modern Australian women. Written in response to another reader, her piece illustrates the Weekly’s willingness to foster dialogue and debate.

Virgil Reilly, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Historian Hannah Viney developed the notion of “feminised politics” to describe the way “the threads of the domestic and the politics that were interwoven” in the Weekly’s coverage in the 1950s. Here we can clearly see that the Weekly allowed readers “politically minded, politically ambivalent or somewhere in between” a forum to engage with political coverage in the 1930s as well.

Towards the end of the decade, as war in Europe began to appear inevitable, Weekly readers were eager to understand the extremist ideologies that threatened world peace. This is apparent in Miss M. Muir’s reader contribution published on August 12, 1939, under the headline: “Need knowledge of foreign politics”.

Muir believed fewer than one in 50 Australian women understood what the Nazi, fascist and communist movements stood for. She proposed the Education Department supply paper lectures to Australian women “on possible political dangers”.

“We should not leave the knowledge of modern foreign politics only to the men,” she argued.

The publication of Muir’s piece in a highlighted box in the “So They Say” column implies the paper’s agreement.