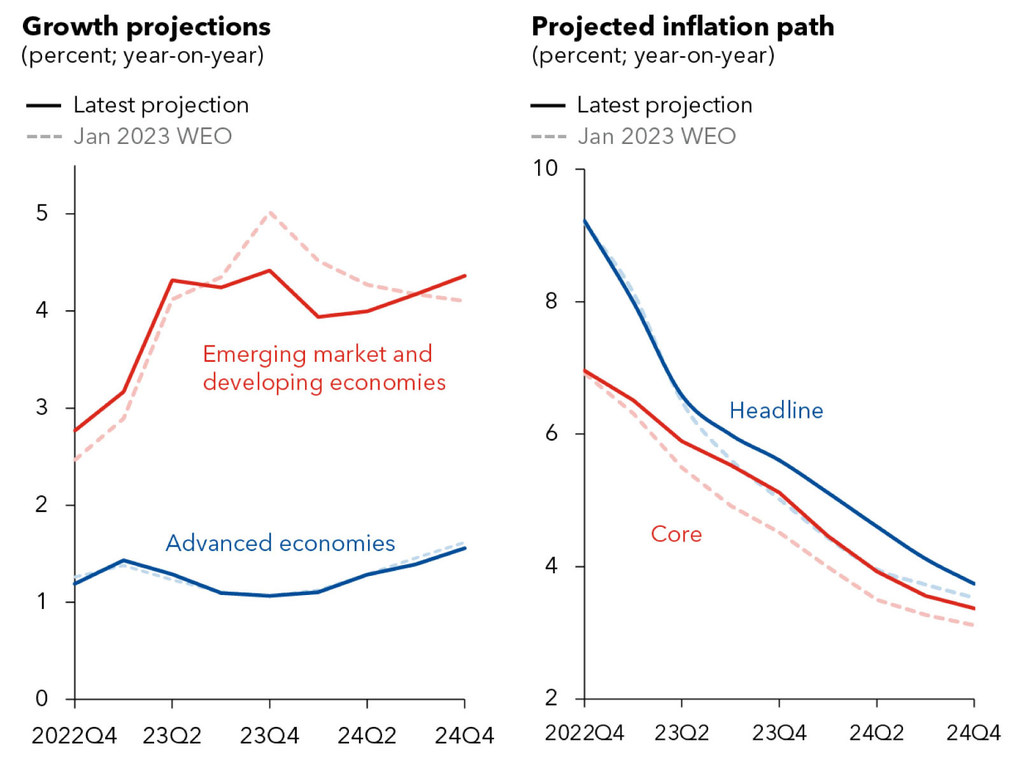

Global inflation is also heading down, signalling that the tightening of monetary policy through major interest rate rises is bearing fruit, though more slowly than initially anticipated, said the IMF’s Director of Research, from 8.7 percent last year to seven percent this year, and 4.9 percent in 2024.

Gradual recovery ‘remains on track’

Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas said the gradual global recovery from both the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “remains on track”, with China’s reopened economy rebounding strongly, while previously disrupted supply chains are unwinding.

He said this year’s economic slowdown is concentrated in advanced economies, especially the Eurozone and in the United Kingdom, “where growth is expected to fall to 0.8 percent and -0.3 percent this year before rebounding to 1.4 and 1 percent respectively.”

In contrast, despite a 0.5 percentage point downward revision, many emerging market and developing economies are picking up, with growth accelerating to 4.5 percent by the end of 2023 from 2.8 percent at the close of 2022.

‘Fragile’ reality

The IMF Director, who also serves as Economic Counsellor, warned that as the recent instability triggered by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and others, shows “the situation remains fragile. Once again, downside risks dominate and the fog around the world economic outlook has thickened.”

He said inflation was still stubbornly high, more than expected by the markets, while falling inflation was mainly due to falling energy and food prices. Only today, the UN’s food agency (FAO) price index, showed another fall, 20 per cent down on the worrying high of a year ago. However, that fall has not translated into similar declines in most supermarkets for most consumers.

Inflation persists

“We expect year-end to year-end core inflation will slow to 5.1 percent this year, a sizeable upward revision of 0.6 percentage points from our January update, and well above target”, said Mr. Gourinchas.

He said that labour markets – reflected in low unemployment rates – “remain very strong in most advanced economies”, which “may call for monetary policy to tighten further or to stay tighter for longer than currently anticipated.”

He said he remained “unconvinced” that there was a big risk of an uncontrolled wage-price spiral, with nominal wage gains continuing to lag behind price increases, implying a decline in real wages.

IMF, April 2023 World Economic Outlook; and IMF staff calculations.

Never an easy ride

He said more worrying were the side effects that the sharp interest rate rises of the last year were having on the financial sector, “as we have repeatedly warned might happen. Perhaps the surprise is that it took so long.”

He argues that due to a prolonged period of muted inflation and low interest rates before the global shocks of COVID and the Ukraine war, the financial sector had “become too complacent”.

The brief instability in the UK gilt market last autumn and the recent banking turbulence in the US “underscore that significant vulnerabilities exist both among banks and nonbank financial intermediaries. In both cases, financial and monetary authorities took quick and strong action and, so far, have prevented further instability”, he reassured.

Jitters still strong

He concluded by warning that a sharp tightening of global financial conditions due to a so-called ‘risk-off’ event, when investors rush to play safe and sell assets, “could have a dramatic impact on credit conditions and public finances, especially in emerging market and developing economies. It would precipitate large capital outflows, a sudden increase in risk premia, a dollar appreciation in a rush to safety, and major declines in global activity amid lower confidence, household spending and investment.”

In that event, he said, growth could slow to just one percent this year, implying near stagnant per capita income. But this is unlikely to happen, the IMF Director suggests: “We estimate the probability of such an outcome at about 15 percent.”