The royal commission into the unlawful robodebt scheme has delivered its findings.

On the final day of public hearings, Commissioner Catherine Holmes highlighted the crucial role of citizen journalists and activists on Twitter. She described the mainstream media reporting as “patchy”, and noted the “remarkably useful and important public service” provided by tweeters covering the scandal from its emergence to the royal commission’s final hearings.

We have been monitoring this Twitter activity closely since 2016. While the nation digests the commissioner’s findings, it’s worth reviewing how a small but committed group of Twitter users tracked the faulty robodebt scheme and helped generate the pressure for a royal commission.

As Twitter declines under Elon Musk’s ownership, the #Robodebt saga is a useful reminder of the platform’s potential for social good.

The beginnings

Around July 2016, after a small pilot program, Centrelink deployed a data-matching algorithm to compare its own datasets against the data held by the Australian Tax Office, to find over-payments to welfare recipients. The algorithm was faulty and unlawful, resulting in the automatic issuing of thousands of incorrect debt letters, some demanding four- and five-figure sums of money.

Vulnerable people reported stories of mental and financial hardship, of long Centrelink call centre queues, and of deep confusion about these debt notices. The Department of Human Services released private information about the few who dared to speak publicly.

But there was no framework for collating the accounts of robodebt victims. The very term “robodebt” hadn’t yet been coined.

The task of documenting the flaws, failures and fatal consequences largely fell to activists who initiated a Twitter campaign under the #NotMyDebt hashtag. In late 2016, they also introduced the “robodebt” moniker, which eventually became the official title of the royal commission.

Almost seven years later, we can document the role of activists like Asher Wolf and their Twitter network in highlighting robodebt’s faults.

The evolution

The robodebt campaign began on Boxing Day 2016, as the first debt notices came to light and #NotMyDebt first trended on Twitter. Over the months to May 2017, a small group of digital activists dedicated their time to tweeting about the issue, setting up the Not My Debt website, and curating stories, evidence and information.

About 100 Twitter accounts initially produced around 50% of the posts, garnering engagement from some 10,000 others. Much of this early activity was dominated by the #NotMyDebt hashtag, but in 2017 #Robodebt gradually took over.

QUT Digital Media Research Centre

By late 2018, #Robodebt was well established – and overlapped considerably with Australia’s perennial hashtag for political discussion, #auspol. Some prominent Labor politicians (Bill Shorten, Anthony Albanese, Mark Dreyfus) also became active during this early timeframe.

This shows how robodebt gradually became a major political – rather than merely administrative – issue, and was increasingly linked with the Liberal/National Coalition government. The first calls for a royal commission to investigate the scheme also appeared during this time.

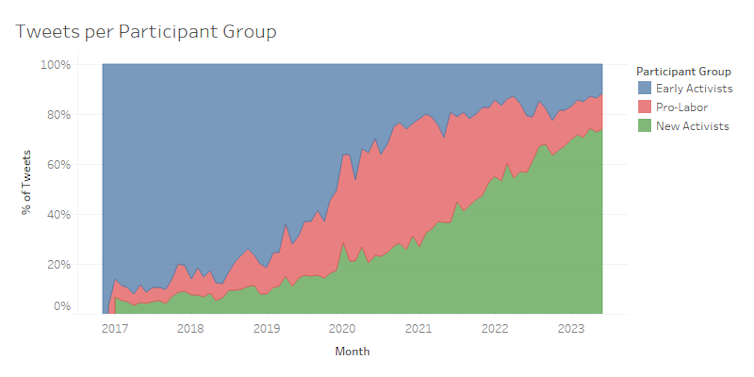

These early activists were central to the early campaign, but also assumed a critical role again as the royal commission commenced in August 2022. Since then, central members of this group – and other core participants who emerged subsequently – have initiated some 40% of all robodebt-related tweets.

From early 2019, particularly after Labor’s loss in the May 2019 election, the composition of the community discussing robodebt changed notably. A second wave of accounts with a strongly pro-Labor stance, including prominent Labor politicians, joined the online campaign.

QUT Digital Media Research Centre

Highlighting robodebt as a failure of the Coalition government, they mobilised their Twitter networks and became increasingly active before the 2022 election. This advocacy continued through to the establishment of the royal commission.

A third group of “new” activists became more active in the final years of the Morrison government. They argued robodebt indicated not only a failure of Centrelink, but of the previous government’s policies. This reflected an overall hardening of anti-Coalition sentiment.

QUT Digital Media Research Centre

The future

The robodebt scheme was illegal, and its continuation despite legal advice was a scandal. Its detrimental impact on thousands of lives has been documented by the royal commission’s hearings.

But much of what we now know about the scheme is thanks to pressure substantially maintained by the initially small number of activists who curated information about the scheme, and popularised the name by which it is now known. As Commissioner Holmes has acknowledged, Australians have benefited from the unpaid public service of these activists.

But what about the next such scandal? Under Musk’s chaotic leadership, Twitter is losing its authentic user base, being overrun by trolls and fake accounts, blocking and shadow-banning critical activists, dropping its moderation teams, and facing technological decay.

Where else will such activism go? None of the other major social media platforms provide the same opportunities for highly public engagement. Few bring together activists, experts, journalists and politicians in the same open space.

If mainstream media coverage is “patchy” and unreliable, if social media communities are under threat from platform owners and unchecked hordes of trolls, where will activists go now to speak truth to power?