Some universities have removed course information from public websites as part of efforts to prevent and respond to gender-based violence, following the stabbing attack this past summer on June 28 at the University of Waterloo.

Police recently added an additional charge of attempted murder to previous charges faced by a man accused of entering a classroom and stabbing three people in a gender studies class. Police believe the attack was motivated by hate related to gender expression and gender identity.

While institutional responses pertaining to increasing security or surveillance technology are important, we can’t build a wall big enough, or an alarm system sharp enough, to protect students from hate, patriarchy or rape culture.

And in some cases, responses like added policing can lead to increased violence, especially for Black, queer, trans, Indigenous, poor or non-binary people.

As one response to the problem of gender-based violence on campus, a project at Queen’s University is piloting gender-based/sexual violence training that meets students where they’re at — the classroom — and engages them through their field of study.

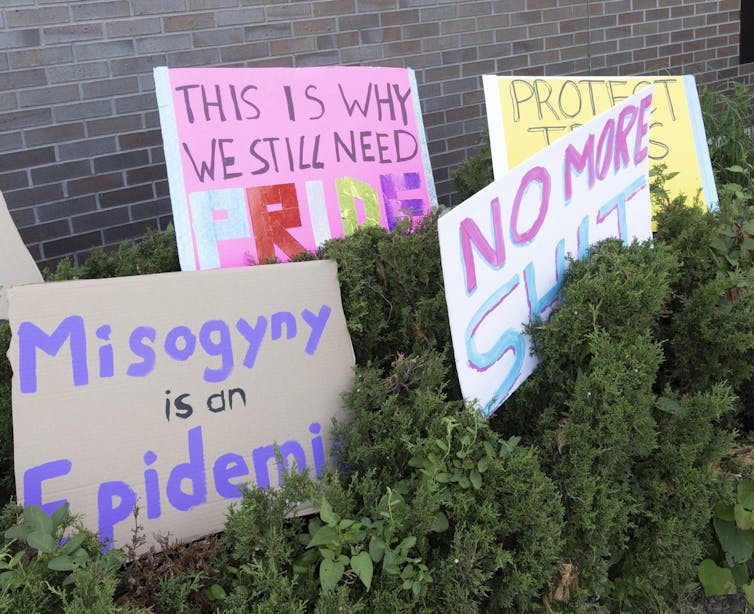

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nicole Osborne

Gender-based violence on campus

The attack at Waterloo is symptomatic of larger issues of sexual and gender-based violence present in society, especially on university campuses.

Gender-based and sexual violence lies at the intersection of racism, sexism and homophobia.

Addressing campus sexual violence: New risk assessment tool can help administrators make difficult decisions

A recent initiative to address and prevent gender-based violence on Canadian campuses reports research conducted about post-secondary students in 2019 showed 71 per cent of students have either witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in a post-secondary setting. Racialized, Indigenous and 2SLGBTQI+ students are disproportionately at risk of sexual assault.

Prevention strategies matter

Prevention strategies for ending gender-based violence must be rooted in challenging inequities through community mobilization, comprehensive education and structural change.

For many universities, the vision is there, but the road is long. And in the context of limited resources, stretched staff and stressed students, how can anti-violence practitioners reach students, especially those not already engaged in these conversations?

One hurdle is the divide between faculty who have been historically tasked with students’ education and knowledge, and administration, who have been tasked with the welfare of students, including responding to and preventing sexual violence on campus. The project we are involved in brings these approaches together.

Reaching more students

(Rebecca Hall), Author provided (no reuse)

Co-authors of this story, Rebecca Rappeport, a sexual violence specialist in the Queen’s University Human Rights and Equity Office, and Rebecca Hall, a professor in the department of global development studies, worked together. We piloted embedding gender-based/sexual violence prevention material into the curricular goals of a global development studies classroom.

The long fight against sexual assault and harassment at universities

Rappeport was invited to lead a one-and-a-half hour workshop during a first-year global development studies class. The workshop focussed on educating students about gender and sexual violence as a social problem, and raising awareness about services available at the university and in the community.

Afterwards, students were asked to engage the analytical tools they were building in the classroom to create proposals addressing this problem.

In keeping with trauma-informed approaches to teaching, students were given advance notice of the collaboration and a “no questions asked” opt-out option with an alternative assignment.

Engineering students involved

The workshop framed campus sexual and gender-based violence as a wicked problem — that is, a problem that requires multiple approaches and intersectional and transdisciplinary collaboration.

Framing gender-based and sexual violence as a wicked problem means that the embedded approach lends itself well to most academic departments — not only to departments focused on feminist theory or equity.

Last winter, Rappeport also brought an embedded workshop, similarly with an “opt out” option, to the second-year mechatronics and robotics classroom of engineering professor Joshua Marshall.

Following Rappeport’s workshop in an engineering class, students were asked to apply their emerging disciplinary knowledge to the problem of gender and sexual violence on campus. In groups, students focused on how their engineering knowledge could contribute creative strategies for addressing campus violence.

Canadian engineers call for change to their private ‘iron ring’ ceremony steeped in colonialism

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nicole Osborne

Students as agents of change

The training met students where they’re at (the classroom) and engaged them through their field of study, with incentives: grades.

This form of engagement reached beyond students who tend to be engaged in gender issues, including significantly more male students.

But beyond this practical aim, in embedding the training in classroom learning, we sought to position the students as agents of change, rather than solely potential perpetrators, victims or witnesses.

Students are encouraged to consider developing new approaches, technologies and policies to work towards ending gender-based violence: to see themselves as inventors, social scientists and leaders.

Preliminary survey results from the two piloted classes showed a significant increase in students’ self-assessment of their knowledge, and their ability to help solve issues related to sexual violence, linking their discipline to these issues. There was almost 100 per cent participation from both classes with over 300 students.

Expanding pilot program

This fall, Rappeport will extend this pilot program with Queen’s engineering, kinesiology and health sciences faculty, with plans for further expansion.

Sexual and gender-based violence can seem like an insurmountable problem, but interdisciplinary thinking encourages creative approaches to social change. Using their own university as a case study allows students to combine their lived experience on campus with classroom knowledge to think through a major social problem.

With this teaching approach, we aim to layer immediate approaches to campus violence with a vision for longer-term structural change. We do so by encouraging students who are often missed in traditional prevention programming to integrate this awareness into their future careers, whether that’s community organizing, writing policy or building robots.

Rebecca Rappeport, Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Community Outreach and Student Support Worker at Queen’s University, co-authored this story.