The odd headlines about little towns in the San Francisco Bay Area just keep coming.

First Woodside, a tiny suburb where several Silicon Valley CEOs have lived, tried to declare itself a mountain lion habitat to evade a new California law that enabled owners of single-family homes to subdivide their lots to create additional housing.

Then wealthy Atherton, with a population of 7,000 and a median home sale price of US$7.5 million, tried to update its state-mandated housing plan. Until very recently, 100% of Atherton’s residentially zoned land allowed only single-family houses on large lots. When the City Council considered rezoning a handful of properties to allow townhouses, strenuous objections poured in from such notable local residents as basketball star Steph Curry and billionaire venture capitalist Marc Andreessen.

A council member argued that the town should “express and explain the specialness of Atherton … to succeed in reducing [the state’s] expectations of us.”

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

On first glance, these might seem like extreme cases of privilege, oddities from quirky California. But as our new book on the politics of housing shows, the ability of small suburban municipalities to limit multifamily housing is more the rule than the exception.

Small governments’ big role in limiting housing

Adding new housing is one of the few ways to limit the escalation of rents and home prices in high-cost metros like San Francisco, New York and Washington, D.C. Even new “luxury” apartments or condos can reduce competition for older units, taking some pressure off rents for people with lower incomes.

However, locating new apartments and townhomes near jobs can be difficult. It means building them in existing communities, where small local governments often constrain housing development.

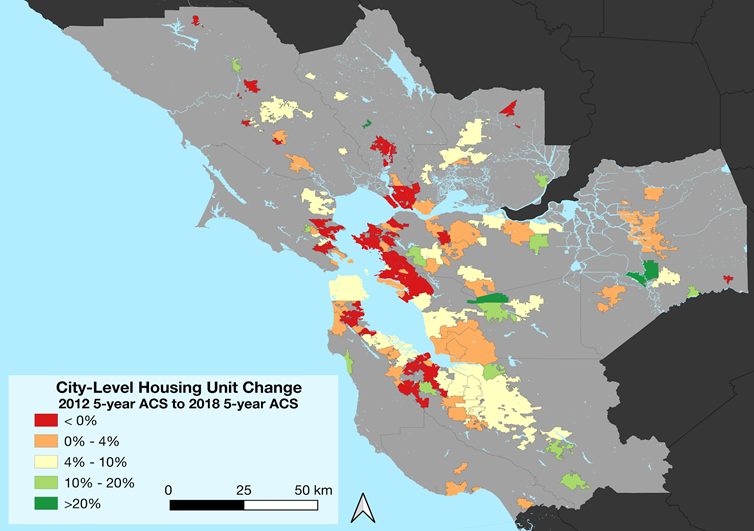

To study the impact small governments’ opposition is having on housing, we used census tract data from California’s metro areas to examine multifamily housing development between the Census Bureau’s 2008-2012 American Community Survey and its 2014-2018 survey, a time when the housing market was rapidly recovering from the Great Recession.

Over that span, according to our statistical estimates, a typical neighborhood-size census tract located within a city of 100,000 residents saw the development of 46 more new multifamily units than an otherwise very similar census tract located within a smaller city of 30,000 residents. In other words, smaller cities, which typically are suburban in nature, added far fewer multifamily units.

An extra 46 new apartments might sound like a small number, but it can make a real difference at the neighborhood level. Nearly half the census tracts in our sample – each with around 1,200 to 8,000 residents – gained five or fewer multifamily units.

Cities across the US face similar struggles

This pattern of slower rates of multifamily housing development in smaller jurisdictions is hardly unique to the Bay Area.

When we examined census data from metro areas nationwide, we similarly found that neighborhoods in small jurisdictions gained fewer multifamily units. We took into account a lengthy list of economic, geographic and demographic factors that could influence neighborhood growth rates, as well as the size of the jurisdiction.

Most big American cities in high-cost regions – think Boston, Denver and Los Angeles – are surrounded by a sea of mostly small independent suburbs.

In many of these communities, residents actively participate in local politics to fight increases in density and multifamily housing. As proposals for new housing are deflected away from these small communities, housing either doesn’t get built, thus raising rents by limiting residential supply, or it gets pushed to far-flung exurbs that are distant from most jobs.

Nicholas Marantz, CC BY-ND

In the San Francisco Bay Area, the communities with relatively high increases in housing in our study tended to be at the urban fringe, while many close-in suburbs had stagnant housing development or even a decline in units.

Inner suburbs could offer housing closer to jobs

Just because a suburb is small in population does not mean that it is far off the beaten track or irrelevant to a region’s economy.

Atherton, for example, maintained its estate-style residential zoning for decades, smack-dab in the middle of a job-rich area. In fact, our data shows that among the Bay Area municipalities with the best geographic proximity to employment, about half are small suburbs of 30,000 or fewer residents.

Transportation is the largest single contributor to U.S. carbon emissions, yet many people end up commuting long distances because housing is so limited and expensive in job-rich areas. However, many inner suburbs’ land-use plans were set decades ago in vastly different economic eras, and many now claim to be “built out” and done with adding housing.

What’s standing in the way?

Why does a municipality’s size matter so much for how many apartments and condos get built? In a word, politics.

Homeowners tend to be the dominant political interest in small suburbs. They may worry that larger or denser residential buildings will decrease their property values, increase traffic or strain local infrastructure. Fears about even minor projects – like the proposal for 16 townhomes near Curry’s estate in Atherton – can get magnified.

To be sure, many homeowners in big cities have similar worries. But in a large, diverse city, anti-growth voices often are counterbalanced by pro-housing interests active in city politics, such as large employers, developers, construction unions or affordable-housing nonprofits.

Ricky Carioti/ The Washington Post via Getty Images

And though a growing set of YIMBY activists – those advocating “yes in my backyard” – agitate in favor of more housing, suburban elected officials typically feel much more political heat from longtime homeowners than from YIMBY activists.

How to unlock more housing where it’s needed

State legislators can unlock the potential for new housing by requiring local governments to relax single-family-only zoning and similar land-use restrictions. Colorado’s governor proposed doing that in 2023, and California has passed similar laws. However, that can be politically risky. Local control of land use is an article of faith in many states.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s effort to enact land-use reforms that would push localities to rezone for more housing hit a dead end in that state’s Legislature in 2023. In California, meanwhile, lawsuits by local governments and neighbors of proposed projects proliferate. And some cities – like Woodside, with its mountain lion sanctuary – attempt to creatively dodge state rules.

Aric Crabb/MediaNews Group/East Bay Times via Getty Images

States could also create incentives for local governments to approve more housing. Certain types of state-collected revenues, such as sales taxes or gasoline taxes, could be distributed to local communities based on each community’s count of bedrooms, with additional credit given for affordable units. This type of incentive might lead local officials to view new apartments as improving their community’s bottom line.

Another approach is for state governments to create metro-level mechanisms designed to represent the needs of housing consumers throughout the region.

States could set up regionwide housing appeals boards authorized to reconsider and potentially overturn anti-housing decisions by cities and towns. Oregon took a more ambitious approach in its largest urban region, Portland. Voters created and then strengthened an elective metro government to not just plan but actually carry out key regional land-use priorities.

With that big-picture view and authority, Portland can put more housing in locations most accessible to jobs and transit while protecting sensitive countryside in outlying areas from vehicle-dependent sprawl. In other words, it can put housing where it’s needed.