According to the eulogies and obituaries written at the time of his death in 1791, Richard Price’s name would be remembered alongside figures such as Benjamin Franklin, John Locke, George Washington and Thomas Paine.

300 years on from his birth in the village of Llangeinor, near Bridgend in south Wales, why has he therefore been lost from our popular memory?

After all, here was a polymath whose lasting contributions ranged across a number of disciplines, including moral philosophy, mathematics and theology. Moreover, Price’s contribution as a public intellectual made a huge impact, not least in international politics.

A useful starting point are the parallels with his friend Mary Wollstonecraft. She was a philosopher, a women’s rights advocate and the mother of Mary Shelley.

Wollstonecraft was both inspired by Price and indebted to him. Indeed, her most influential texts are directly linked to Price and the pamphlet war known as the Revolution controversy.

In these texts, influential thinkers discussed the political issues arising from the French Revolution. It has subsequently been recognised as a formative debate in terms of modern political ideas.

It was Price who sparked the controversy with a sermon in 1789 entitled A Discourse on the Love of Our Country, in which he supported the opening events of the revolution in France.

He declared it to be a continuation of the spreading of enlightened values and ideas introduced by the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in England.

This provoked a response from the philosopher and Anglo-Irish Whig MP Edmund Burke, with his famous text, Reflections on the Revolution in France.

This is regarded as a formative text of modern conservative thought. It defended the importance of the traditional institutions of state and society while warning of the excesses of revolution.

In response, Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Men in 1790. It was both a critique of Burke and a defence of Price, who died a year later.

Then in 1792, she wrote her profoundly influential A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, explicitly extending dissenting ideals to women, with a searing social critique.

Both Price and Wollstonecraft would subsequently be written out of history.

Price’s biographer, Paul Frame, suggests this can be partly accounted for by events in France and the violent turn to terror during the French Revolution.

As a result, Frame suggests Burke was “the man who had accurately predicted the direction of the Revolution”. This “undermined the more optimistic faith in rationalism and natural rights” of Price and others.

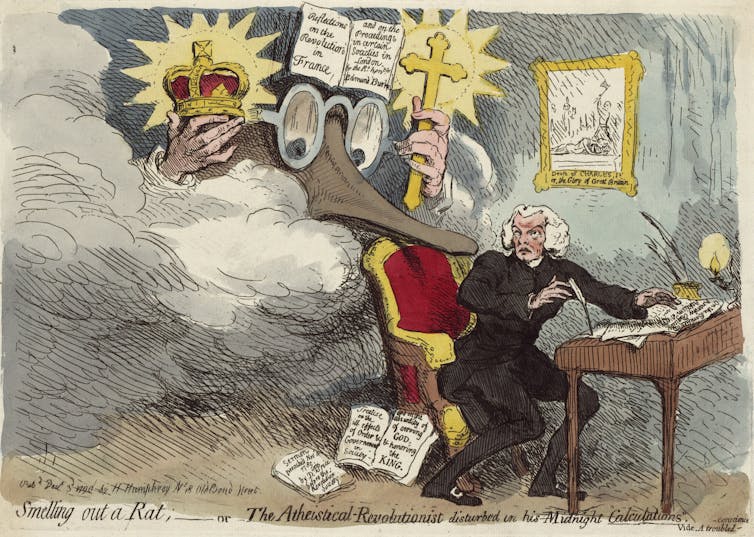

They both also suffered in terms of their personal reputation. Price became a caricature of the picture painted by Burke, captured in the cartoons of the day.

Library of Congress

Wollstonecraft was posthumously undone by the candid biography of her widower, its contents deployed maliciously by those who sought to undermine her. Thankfully, her works and good name were recovered by the feminist movement.

As Frame suggests however, there were deeper, structural factors at play.

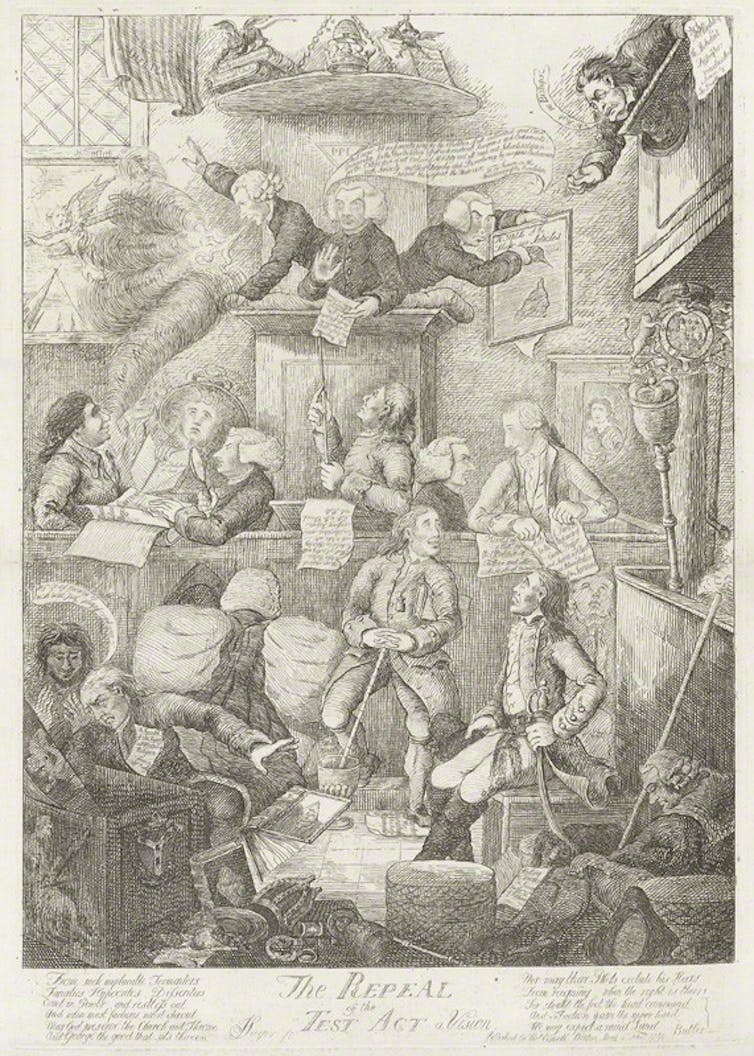

Price was the embodiment of a reformism the British establishment had a material interest in thwarting. He represented a dissenting community whose nonconformist Christian denominations were in opposition to the established church and discriminated against.

Price spoke out against the crown, slavery and chauvinistic nationalism. He advocated equality, democratic principles and civic nationalism.

The hostility towards the progressive forces he embodied was symbolised by the Seditious Meetings Act introduced in 1795 to stifle the reform movement.

James Sayers

There would have been very real consequences had it been Price and his ilk – and not Burke – who were lionised as the spirit of Britain (a state less than a century old at the time). Arguably, we still live with the ramifications today.

Price’s politics eventually had their day as the social tumult of the 19th century meant the tide of reform could not be stemmed.

Burke’s conservatism, however, conceivably still symbolises where the balance of power sits in terms of the UK’s political culture. The Tory party is often still regarded as the natural party of power, and deference towards the ruling classes remains.

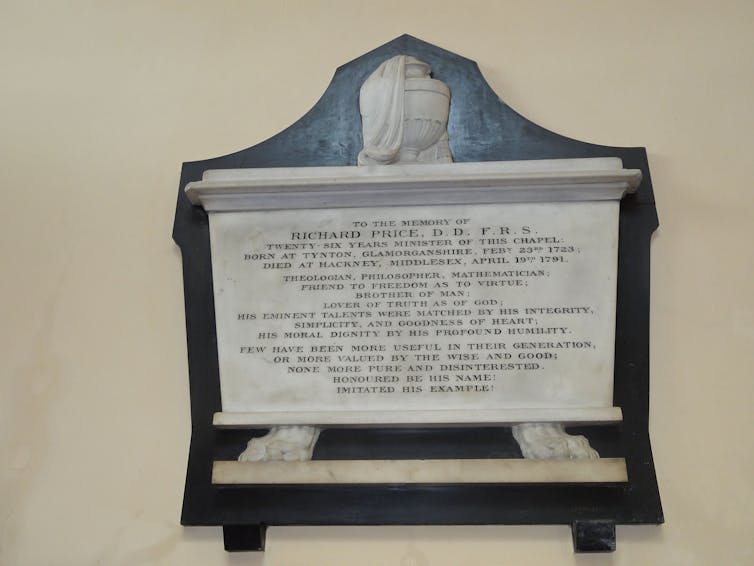

Jonathan Cardy, CC BY-NC-SA

Given the collective amnesia towards him within Britain, it is perhaps apt that celebrations of Price’s life and works should begin this month with a talk at the American Philosophical Association in Philadelphia.

There will, however, be a programme of events at home to reflect on his contribution and contemporary relevance.

This will include a birthday celebration in Llangeinor, an academic conference, and a play.

If he has not been celebrated by a British culture, for which he had such high hopes, then it is high time it happened in Wales, at the very least.