In the wake of Sunday’s tragic Bondi shooting, conspiracy theories and deliberate misinformation have spread on social media.

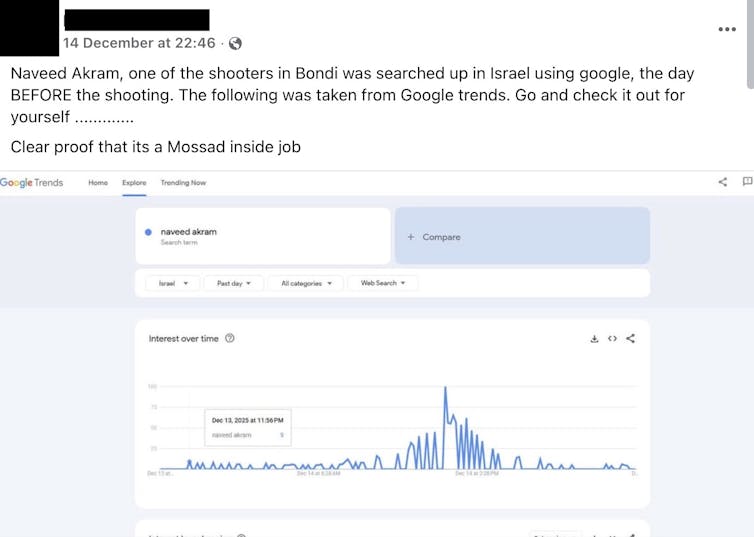

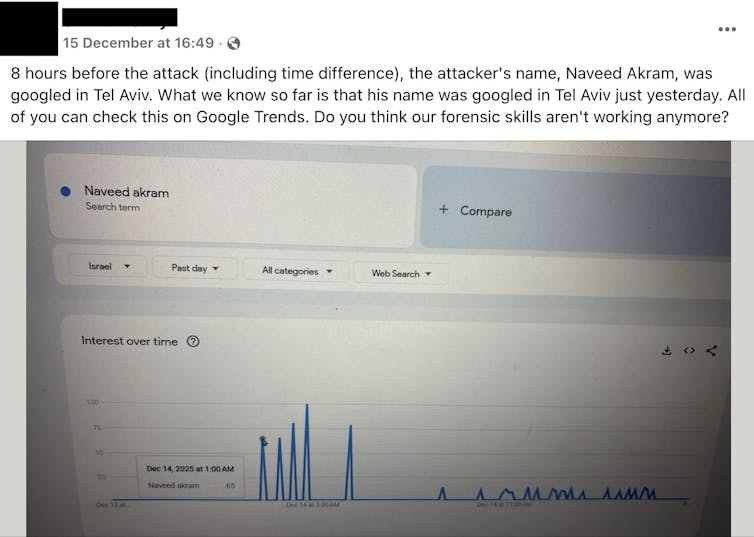

One thing some people have latched onto is the idea Google Trends data show a spike in searches for “Naveed Akram” – the name of one of the attackers – from Tel Aviv (or other locations) before the shooting occurred. In a surprising lateral jump, this is taken to show Akram must be an Israeli agent.

Similar stories did the rounds when US right-wing activist Charlie Kirk was killed in September, and after an attack on US National Guard members in November.

So what’s going on here? Google told the ABC Google Trends may sometimes show searches when none actually happened due to “statistical noise”.

I have studied the mechanics of Google Trends extensively in my research, and I can confirm this is true – and the “noise” can lead to strange results, especially when looking at searches for unusual terms or coming from small areas.

How does Google Trends work?

Google Trends shows information about what users are searching for at different places and times. The data it uses are what statisticians call a “time series”, but they are unusual in a couple of ways.

First, you can very easily select different time scales, such as minute-by-minute and year-by-year.

Second is the fact the data are only a small sample of the true gigantic volume of Google searches. Time series normally contain all available data (such as these statistics on annual hospitalisations).

The Google Trends help page explains this as follows:

While only a sample of Google searches are used in Google Trends, this is sufficient because we handle billions of searches per day.

Statistical noise and rare searches

However, my research has shown that queries related to terms that are not widely searched (such as “Naveed Akram” before the shooting) or in small geographical regions (where there are fewer people doing searches) can display a wide variation of results from one sample to the next.

Many of the misleading social media posts show Trends results from a small region (such as only the city of Tel Aviv), which exacerbates the variation. The high variation causes a very distinct pattern of zero or near-zero values with some isolated big spikes, which is very evident in the post below.

These spikes are often caused by “statistical noise” in the data – small random fluctuations that are smoothed out when we look at a larger number of events. You can see this clearly when you compare with searches that have high volume.

How Google Trends results change over time

Another misconception about the data is related to time. Some posts mention how the displayed results seem to change from one view to the next. This is, in fact, exactly what to expect with Google Trends data.

This is a combination of the time scale used and the fact Google uses only a sample of the full data. To get accurate results, one has to aggregate many samples of Google Trends data.

However, this presents a new challenge. For short-term data (such as that typically used in these social media posts), Google continually updates results in real time. For longer-term data, Google only adds one new sample per day (though we have developed methods to get around this).

What the numbers in Google Trends really mean

A third misconception is that the numbers shown on Google Trends charts are the number of searches for a given term. However, the Google Trends help again explains that the values are “normalised to the time and location” and then “scaled on a range of 0 to 100”.

This means the time point in the series with the highest number of searches is set to 100, and all other points are scaled relative to that. So if the maximum number of searches was ten, it would show up as 100 – and if there were three searches at another time, this would show up as 30 (although Google does suppress very low-volume searches).

X

In a sense, the number for each time point represents the likelihood that a search containing the specified terms would occur in that place at that time.

So a post about search trends for the alleged killer of Charlie Kirk claiming there are “Less than 1 in 1 BILLION odds of it happening” is incorrect.

It is, in fact, highly probable: if “Tyler James Robinson” (Charlie Kirk’s alleged killer) had 30 searches, and “Lance Twiggs” (Robinson’s partner) had 40, one would see exactly this pattern (if 40 is scaled to 100; 30 is accordingly scaled to 75).

The power of common sense

Even without understanding all this information about Google Trends data, some common sense can also help. For example, there are many people named Naveed Akram, including a Pakistani footballer named Muhammad Naveed Akram.

That there might have been a few searches for “Naveed Akram” even before December 14 is therefore not surprising. (Google Trends returns any search containing the query, so “Naveed Akram” will also return “Muhammad Naveed Akram”.)

Google Trends data can be incredibly useful for understanding events in real time. For example, it has been used to predict — with a margin of error — the outcomes of elections and referendums.

However, to do so properly, and not perpetuate fiction, one has to understand the data and interpret the results properly. And Google Trends certainly does not tell us anything about Naveed Akram and the Bondi terror attack.