Nearly a quarter of countries used force to prevent religious gatherings during the pandemic; other government restrictions and social hostilities related to religion remained fairly stable

For the latest data on government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion, read our report “Globally, Government Restrictions on Religion Reached Peak Levels in 2021, While Social Hostilities Went Down” and visit the interactive “Religious restrictions around the world.”

In 2020, the year the COVID-19 pandemic took hold globally, many countries banned or limited public gatherings to slow its spread. This report – Pew Research Center’s 13th annual study of restrictions on religion around the world – focuses on how the lockdowns and other public health measures affected religious groups, and how they responded. Among the key findings:

- Authorities in nearly a quarter of all the countries and territories studied (46 out of 198, or 23%) used physical means, such as arrests and prison sentences, to enforce coronavirus-related restrictions on worship services and other religious gatherings.

- Religious groups filed lawsuits or spoke out against the public health measures in 54 of the 198 countries (27%). A common complaint was that some churches, mosques, synagogues and other houses of worship were treated unequally – either by comparison with secular gathering places, like shops and restaurants, or by comparison with other religious groups.

- In 69 countries and territories (35%), one or more religious groups defied public health rules related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

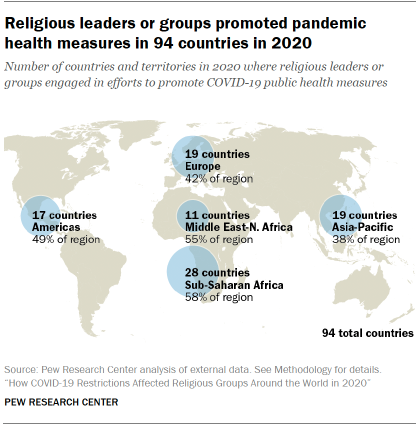

- In an even larger number of countries (94, or 47%), religious leaders or groups promoted public health measures to slow the spread of the coronavirus by encouraging followers to worship at home, observe social distancing or take other precautions, such as hand-washing and mask-wearing.

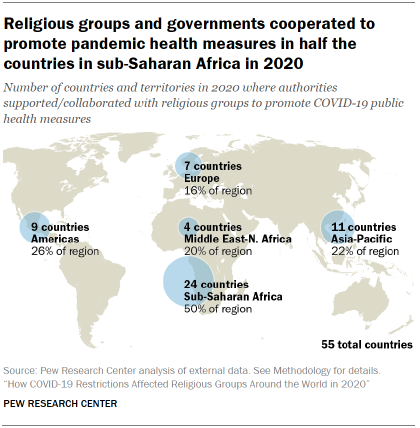

- News articles and other information sources identified 55 countries (28%) where government officials and religious groups collaborated on efforts to stem the pandemic. In some countries, different religious groups both defied and promoted lockdowns or other public health restrictions.

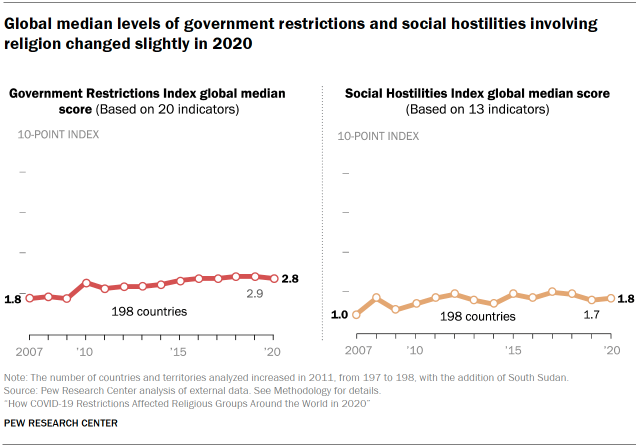

Meanwhile, other kinds of restrictions on religious belief and practice remained fairly stable at the global level in 2020. The median score on Pew Research Center’s 10-point Government Restrictions Index (GRI), which measures laws, policies and actions by government officials toward religious groups, fell slightly from 2.9 in 2019 to 2.8 in 2020. The median score on the 10-point Social Hostilities Index (SHI), which captures hostile acts against religious groups by private individuals and organizations, rose by a similar margin, from 1.7 in 2019 to 1.8 in 2020.

This report first summarizes the data on pandemic-related restrictions on religious activity, with specific examples from many countries. Then it describes the findings of the 13th annual study of overall restrictions on religion around the world, including changes in the index scores at the global and regional levels.

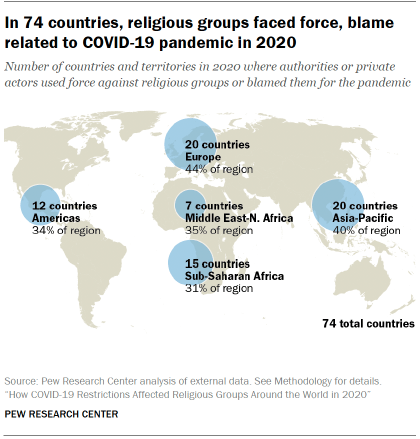

In more than a third of the 198 countries and territories analyzed, religious groups were subjected to various types of force or blame related to the coronavirus outbreak in 2020. In 74 countries (37% of all analyzed), the study identified at least one of the following: (1) governments used force to impose limits on religious gatherings; (2) governments, private groups or individuals publicly blamed religious groups for the spread of the coronavirus; or (3) private actors engaged in violence or vandalism against religious groups, linking them to the spread of COVID-19.

These incidents were spread fairly evenly around the world, including in 12 countries in the Americas (34% of countries in the region), 20 countries in the Asia-Pacific region (40%), 20 countries in Europe (44%), seven countries in the Middle East-North Africa region (35%) and 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (31%).

Nearly a quarter of governments used force against religious groups to enforce COVID-19 rules

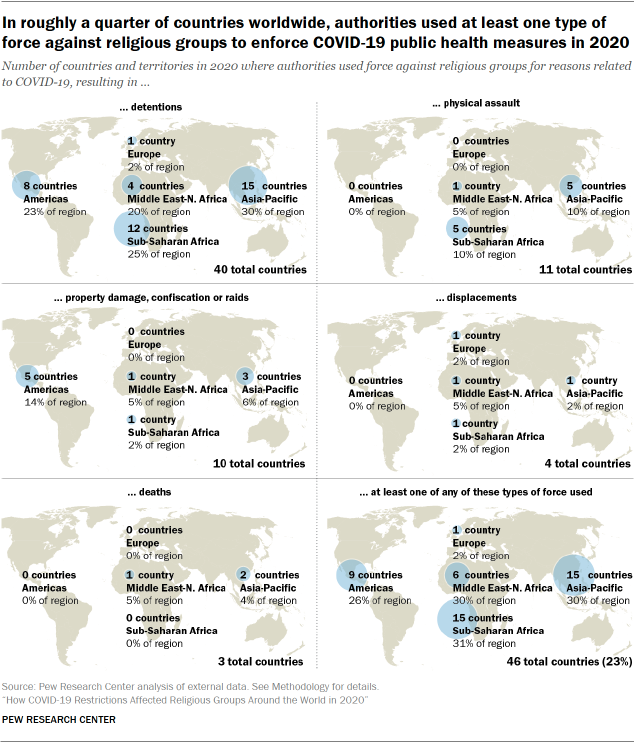

In 46 countries and territories, or 23% of all those examined in the study, government authorities used force to impose coronavirus-related bans or limits on religious gatherings in 2020. That count includes only places where the bans or limits on religious gatherings were carried out with physical force, such as arrests and detentions; physical assaults; damage, confiscation or raiding of private property; displacements of people from their homes; or killings.

This study does not attempt to determine whether the use of physical force was justified in each case. And the numbers cited here do not include countries that enforced bans or limits on religious gatherings with less stringent methods, such as fines for violations.

Detentions were the most common type of force used against religious groups when they were deemed in violation of public health guidelines, according to the sources examined in the study. In 40 of the 46 countries where force was reported to have been used, governments arrested and held worshippers or religious figures for gatherings that violated public health measures, or for other actions by religious groups relating to the pandemic.

In Azerbaijan, for example, police detained Shiite worshippers who had gathered in several cities to commemorate Ashura, an Islamic holiday, in violation of a ban on gatherings. In the United States, police in New Jersey arrested 15 people at a rabbi’s funeral that violated the state’s ban on public gatherings. The arrests were made after some mourners became unruly and argumentative when police tried to disperse the crowd, according to media reports.

In India, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced in April 2020 that more than 900 members of the Islamic group Tablighi Jamaat and other foreign nationals (most of whom were Muslim) had been placed “in quarantine” after participating in a conference in New Delhi allegedly linked to the spread of early cases of coronavirus. (Many of those detained were released or granted bail by July 2020.)

And in Myanmar (also called Burma), a Buddhist-majority country, leaders of religious minority groups complained that pandemic-related health measures were enforced much more harshly against Muslims and Christians than against Buddhists. For example, 12 Muslim men received prison sentences of three months for holding a religious gathering in a house in Chanmyathazi Township. In a separate case, a Christian pastor was sentenced to three months in prison for holding a prayer session. In contrast, none of the 200 attendees at a Buddhist monk’s funeral were arrested; the organizers were fined instead.

In 11 countries, authorities’ use of force against religious groups included physical assaults, according to the sources examined in the study. In Comoros, Gabon and Nepal, police used tear gas to disperse religious gatherings that violated COVID-19 lockdown rules. In China, more than 300 members of the Church of Almighty God (also known as Eastern Lightning) were arrested in February and March 2020 during pandemic-related identification checks and home inspections, and some were subjected to beatings and electric shocks, according to the U.S. State Department’s 2020 Report on International Religious Freedom. And in Zambia, human rights organizations asserted that police sometimes used excessive force against religious groups when enforcing COVID-19 rules. In April 2020, for example, police assaulted a group of church leaders in a town called Mkushi where they had gathered in violation of public health guidelines.

Authorities in 10 countries confiscated property or carried out raids to shut down religious gatherings. In Israel, police targeted Jewish communities deemed to be at the epicenter of outbreaks, deploying security forces in ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods, breaking up gatherings at synagogues and sending helicopters to hover low over crowds. In Mexico, authorities raided a church in the state of Durango during a clandestine Mass and expelled the worshippers. And in South Korea, police raided the Sarang Jeil Church, which was reportedly at the center of a coronavirus outbreak in Seoul and the surrounding Gyeonggi Province. The headquarters of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus also was raided, largely due to its violation of public gathering restrictions and the church leader’s refusal to provide health authorities with membership lists for contact tracing.

In four countries, authorities displaced religious figures by expelling or repatriating them back to their country of origin. For example, in Equatorial Guinea, authorities disbanded two religious groups – the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, run by missionaries from Brazil, and the locally based Ministry of Liberation, Health and Prophecy – for violating pandemic-related restrictions. They also canceled the residence permits of the groups’ foreign pastors and other leaders and ordered their deportation. And in Singapore, authorities deported five South Koreans who were part of an unregistered local chapter of the Shincheonji Church, in part because of the group’s links to COVID-19 clusters in South Korea.

Pandemic-related killings of religious minorities were reported in three countries in 2020, according to the sources analyzed in the study. In India, two Christians died after they were beaten in police custody for violating COVID-19 curfews in the state of Tamil Nadu. In Indonesia, authorities killed six members of a banned organization called the Islamic Defenders Fund (FPI) – a group they were shadowing partly because its leader failed to appear for a summons on a charge that he had violated COVID-19 protocols. While FPI has long been accused of engaging in violence, an official inquiry after the incident found the government had violated human rights in four of the killings because the FPI members were in police custody when they died. And in Yemen, Houthi rebels in control of territories encompassing most of the country’s population used the pandemic as an excuse to expel thousands of Ethiopian migrants, many of whom were Christians, according to the U.S. State Department. Dozens reportedly were killed during the expulsions.

Roughly a quarter or more countries in each major geographic region – with the exception of Europe – had instances where governments used one or more of these types of force when religious groups did not follow public health measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (31% of countries in the region), 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific region (30%), six in the Middle East-North Africa region (30%) and nine countries in the Americas (26%). In Europe, only one country, Montenegro, fell into this category. Police arrested numerous Serbian Orthodox clergy in several Montenegrin towns on charges that they violated restrictions on outdoor public gatherings and other public health measures.

Countries where authorities blamed religious groups for spread of virus

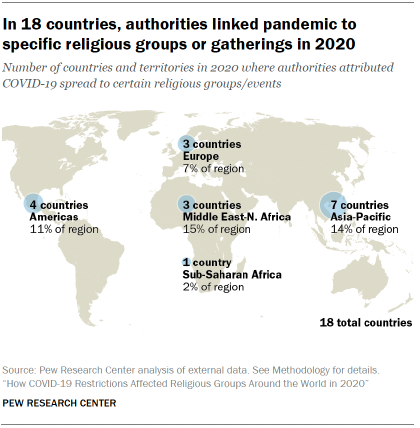

In addition to counting instances of governments using force against religious groups, this study looks at whether public officials in each country attributed or linked the spread of COVID-19 to specific religious groups or gatherings in ways that singled out those groups for blame. Such incidents were reported in 18 countries (9% of the total analyzed). In some cases, religious groups were explicitly accused of having caused outbreaks, which the groups’ leaders said resulted in stigmatization, scapegoating or profiling.

Pew Research Center did not determine whether there was truth to these accusations. But the figures cited in this report do not include cases in which public officials warned broadly that the virus could be spread at crowded, indoor gatherings, including religious services, without singling out particular groups.

In Pakistan, Shiite Muslims of Hazara ethnicity who returned from a pilgrimage to Iran were targeted, “scapegoated” and blamed for the spread of the virus by officials in Balochistan province, according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF). In Cambodia, which has a Buddhist majority, the government in March 2020 began officially singling out Muslims by including a “Khmer Islam” category in statistics on infection rates, after reports emerged of Cambodian Muslims returning to the country with COVID-19 from a religious gathering in Malaysia. And in Canada, Hutterites (an Anabaptist group living in communes throughout North America) claimed they faced social discrimination after provincial governments publicized COVID-19 outbreaks in their communities, which they said amounted to “cultural and religious profiling.”

Social hostilities involving religion and COVID-19

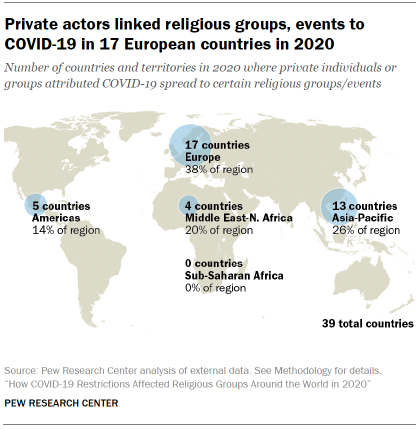

In addition to analyzing cases in which governments reportedly used force against religious groups or blamed them for the pandemic, this study examines incidents in which private individuals or organizations targeted religious groups through social hostilities related to the outbreak.

The sources reported 39 countries (20% of the total number studied) in which private individuals or organizations linked the spread of the coronavirus to religious groups in 2020. This includes individuals or organizations that used hostile or inflammatory speech about particular religious groups.

In more than half of these countries (23 out of the 39), such comments were made against Jews. In France, social media users shared antisemitic tropes with caricatures of a former Jewish health minister that depicted her poisoning a well – an insinuation that Jews were responsible for the pandemic. (This trope dates back to the 14th century, when Jews were accused of spreading the Black Plague by poisoning food and wells, and they were the victims of mass killings.) In the United Kingdom in 2020, antisemitic conspiracy theories spread online, claiming that Jews were in control of the global lockdowns and were using the pandemic to “steal everything.” In Morocco, a man was arrested for social media posts in which he accused a Jewish citizen and a foreign national of infecting many people with COVID-19.

The sources also indicate that Muslims were targeted by private individuals or organizations in connection with the coronavirus outbreak in 15 countries (including some Muslim-majority countries).

In Cambodia, Muslims reported facing widespread suspicion and discrimination after the government created the previously mentioned “Khmer Islam” category in official statistics on infection rates. Some Cambodian merchants reportedly refused to sell goods to Muslims, and some non-Muslims wore masks only in the presence of Muslims. Meanwhile, in Pakistan, Shiite Hazara Muslims were targets of hate crimes and discrimination by Sunni extremists and other social media users who, according to USCIRF, had been “egged on by government and media claims that the virus came from pilgrims returning from Iran.” Some social media users in Pakistan also labeled COVID-19 the “Shi’a virus.” And in India, Islamophobic hashtags like #CoronaJihad circulated widely on social media, seeking to blame Muslims for the virus.

Christian groups were targeted by private individuals and organizations in nine countries. In Turkey, an Armenian Orthodox church’s door was set on fire, and news reports said the man told police that he acted because “they [Armenian Christians] brought the coronavirus” to Turkey. In Egypt, conspiracy theories blamed the pandemic on the Coptic Orthodox Christian minority, which international Christian observers said exacerbated the discrimination the minority group already faced.

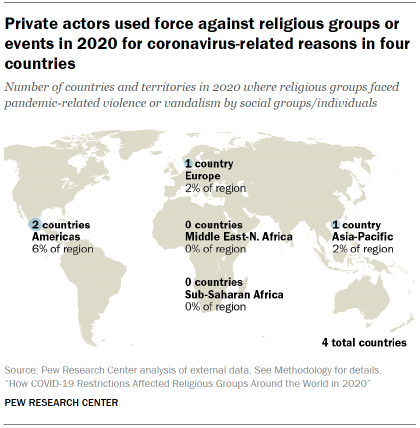

Pandemic-related social hostilities against religious groups that involved physical violence or vandalism by private individuals or organizations were reported in just four countries – India, Argentina, Italy and the United States.

In India, there were multiple reports of Muslims being attacked after being accused of spreading the coronavirus. In Argentina and Italy, properties were vandalized with antisemitic posters and graffiti that linked Jews to COVID-19. In Italy, for example, authorities found graffiti of a Star of David with the words “equal to virus.” And in the U.S., a Mississippi church burned down in an arson attack about a month after its pastor sued the city over public health restrictions on large gatherings. Investigators found graffiti in the church parking lot that said, “Bet you stay home now you hypokrits.”

Criticism and defiance of COVID-19 measures by religious groups

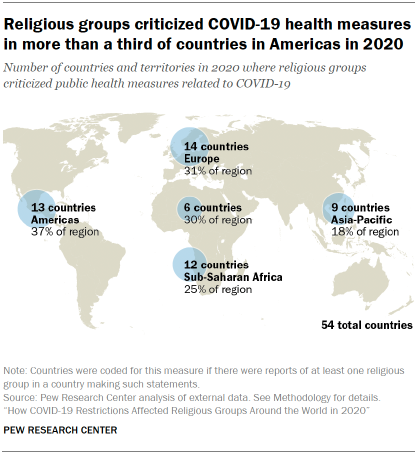

This study also looks at whether religious groups in each country publicly criticized or objected to COVID-19 regulations. During 2020, religious groups in 54 countries (27% of all analyzed) criticized public health measures related to COVID-19 – such as restrictions on public gatherings – and in many cases alleged that the measures violated their religious freedom, according to the study’s sources.

In Argentina, for example, the president of the interfaith Argentine Council for Religious Freedom criticized the government for not declaring priests, ministers and other employees of religious organizations to be “essential” workers like doctors, nurses and home health care providers.

In Sri Lanka, Muslims objected to mandatory cremations of those who died from COVID-19, saying the policy violated the religious rights of the deceased and their relatives to have a traditional Islamic burial, and noting that international public health guidelines allowed for burials of coronavirus victims. And in the United States, lawsuits over state and municipal health restrictions were filed by numerous religious groups, including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn and several synagogues and rabbis in New York, contending that pandemic-related restrictions violated the guarantee of “free exercise” of religion contained in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

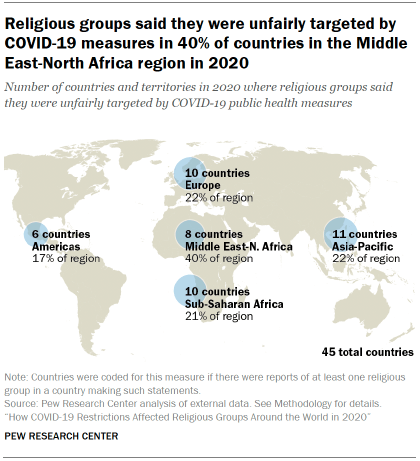

In many of the complaints and protests around the world, religious groups also claimed that pandemic-related laws and regulations unfairly targeted them either by comparison with nonreligious businesses and institutions, such as shops and restaurants, or relative to other religious groups. This type of complaint was recorded in 45 countries (23% of the total).

In 18 of these countries, religious groups claimed nonreligious businesses or institutions were treated more leniently. In the Philippines, for instance, religious leaders said their institutions were unfairly targeted for closure when shopping malls and other stores were allowed to reopen for business before houses of worship could reopen for religious services. Similarly, in Belgium, a group of Catholics asked the Council of State to overturn the suspension of church services, pointing out that large crowds were permitted to go to shops but not to Mass. They said they found the regulations against religious groups to be “disproportionate” and a violation of religious freedom guaranteed in the country’s constitution.

In other cases, there were reports that restrictions were unevenly applied to religious groups or denominations. In Algeria, for example, mosques and Catholic churches were allowed to reopen in August 2020, while Protestant churches had to remain closed through the end of the year.

In all five major geographic regions of the study, at least a quarter of the countries had one or more religious groups that criticized public health measures as violations of religious freedom, alleged they were unfairly targeted by the measures, or made both kinds of objections. This includes 16 countries in the Americas (46% of the total for the region), eight in the Middle East-North Africa region (40%), 17 in Europe (38%), 17 in sub-Saharan Africa (35%) and 15 in the Asia-Pacific region (30%).

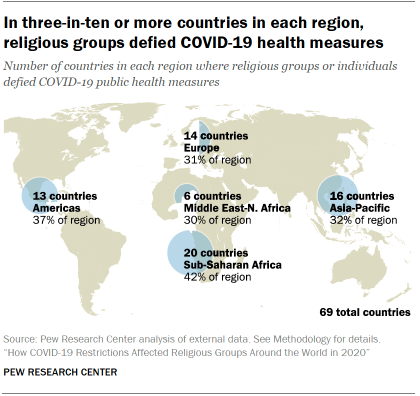

The sources used in this study also identified 69 countries (35% of the 198 studied) where one or more religious groups defied public health restrictions related to the pandemic. In Bangladesh, for example, tens of thousands of people attended the funeral of a prominent Islamic preacher despite an agreement between police and the preacher’s family to limit attendance to 50 people. And in the United States, a pastor in Louisiana held services at his church in defiance of stay-at-home orders by the governor, telling hundreds of attendees they had “nothing to fear but fear itself.” Meanwhile, in Australia, groups of ultra-Orthodox Jews met for prayer in a private courtyard in Melbourne in violation of a national ban on gatherings at places of worship (and against a similar directive by local Jewish leaders). In Angola, at least dozens of religious leaders and worshippers in provinces across the country faced charges in March 2020 that they violated bans against large gatherings, including 22 Seventh-day Adventist pastors in Bie, Huambo, Benguela and Lunda Norte.

In each of the regions studied, at least three-in-ten countries had such reports about religious groups.

Cooperation between religious groups and governments

Along with tensions between religious groups and authorities regarding COVID-19 regulations, there were many examples in 2020 of governments collaborating with religious groups to promote public health measures in faith communities. In some cases, governments met or consulted with religious groups before implementing lockdown measures or supported religious groups during the pandemic through additional funding. Media sources identified such collaborative efforts in 55 countries (28%), including half the countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Benin, for example, the government consulted with religious leaders and an inter-ministerial committee before imposing lockdown measures and later reopening places of worship. In some parts of the country, local officials relied on religious leaders to share accurate information about the coronavirus, help stop the spread of misinformation and encourage public health measures such as social distancing, hand-washing and mask-wearing.

In addition, religious leaders or groups in 94 countries (47% of all those analyzed in the study) encouraged followers to worship at home, promoted online worship, or engaged in other efforts to stop the spread of the virus, such as mask wearing and social distancing. Media sources reported such efforts in more than half the countries in sub-Saharan Africa (28 of 48) and the Middle East-North Africa region (11 out of 20), as well as 49% of countries in the Americas, 42% in Europe and 38% in the Asia-Pacific region. In Lesotho, for example, both evangelical Protestant and Catholic churches were active in spreading awareness about the pandemic and encouraging safety measures. And in Albania, religious leaders supported the government’s health measures and canceled religious gatherings.

Media sources in some countries identified examples of both cooperation between religious groups and governments, on the one hand, and defiance of public health rules by religious groups, on the other. For instance, in Liberia, some Christian groups initially resisted lockdown measures, including a large group of worshippers from the Saint Assembly Church in Monrovia who gathered on a field in late March 2020 to pray for the nation. When the worshippers did not heed police instructions to disperse, some were arrested. Yet, in the same country, the government collaborated with an interreligious council on a “faith-based action plan” to train more than 500 field workers in Christian and Muslim communities to help stop the spread of the virus.

For information on all COVID-19 questions and countries that were coded, see Appendix E.

Overall restrictions in 2020

The new analysis of pandemic-related restrictions was, for obvious reasons, not conducted in previous years. But Pew Research Center’s reports on global restrictions on religion have used a consistent set of measures – separate from the coronavirus-related questions – to examine government limits and social pressures on religious beliefs and practices in nearly all countries and territories around the world since 2007.

The latest analysis finds that the global median level of government restrictions on religion – that is, laws, policies and actions by authorities that impinge on religious beliefs and practices – fell slightly, from 2.9 in 2019 to 2.8 in 2020 on the 10-point Government Restrictions Index (GRI). While the year-to-year change was relatively minor, scores on the GRI remain substantially higher than they were in the first year of the study, 2007, when the global median score stood at 1.8.

Meanwhile, the global median level of social hostilities – measuring religion-related violence and harassment by private individuals or groups – ticked up from 1.7 in 2019 to 1.8 in 2020 on the 10-point Social Hostilities Index (SHI), after two consecutive years of decline. The global median score on the SHI, which has fluctuated more than the median GRI score over the course of the study, also has increased since 2007, when it was 1.o.

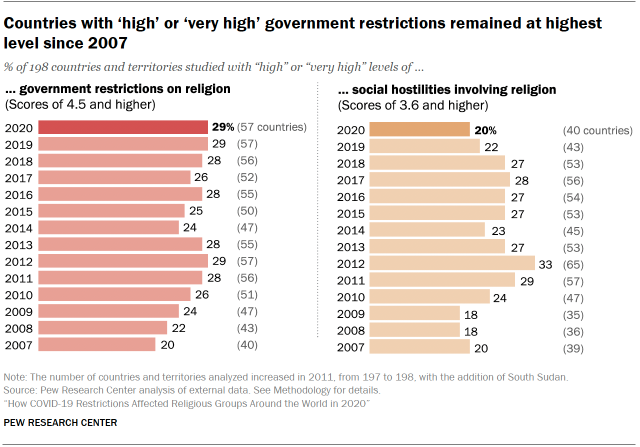

Another way of examining these trends is to look at the number of countries that had either “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions or social hostilities involving religion. In 2020, this combined figure remained unchanged for government restrictions: 57 countries (29%) had at least “high” levels of government restrictions in both 2019 and 2020 – a peak number for the study. But the number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities dropped from 43 countries (22%) in 2019 to 40 countries (20%) in 2020, staying well below the peak of 65 countries (33%) reached in 2012.

When looking at overall restrictions in 2020, the study finds 77 countries (39%) with “high” or “very high” levels of either government restrictions or social hostilities (or both). This figure is up from 75 countries (38%) in 2020, but it remains below the peak of 85 countries (43%) from 2012.

For more information on how restrictions have changed since 2019, see the following chapter.

CORRECTION (Jan. 26, 2023): A previous version of Chapter 2 “Physical harassment related to religion occurred in more than two-thirds of countries in 2020” misstated that “the religiously unaffiliated” category includes atheists, agnostics, humanists and others who do not identify with a religion. The wording has been changed to say that the unaffiliated category instead includes atheists, agnostics and others who do not identify with a religion. Humanists are coded in a separate category from the unaffiliated in this study. This change does not substantively affect the findings of this report.