Governor Richard Bourke’s written proclamation of terra nullius was made on October 10, 1835. The original document now resides in the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

The proclamation was enacted to invalidate the treaty struck between John Batman and the Wurundjeri and Woi Wurrung people, who owned the land on which Melbourne now stands. Though the term “terra nullius” does not appear anywhere in its two pages, its claim of ownership over the entire continent would become the legal justification for the dispossession and inhumane treatment of First Nations people in Australia.

Review: Barron Field in New South Wales: The Poetics of Terra Nullius – Thomas H. Ford and Justin Clemens (Melbourne University Publishing)

Most Australians are familiar with the concept of terra nullius as a legal fiction that was overturned in the High Court of Australia’s Mabo decision of 1992. But the circumstances around its beginnings are often forgotten.

In Barron Field in New South Wales: The Poetics of Terra Nullius, Thomas H. Ford and Justin Clemens invite us into a mostly unknown part of Australia’s legal and literary history in a way that rejuvenates the debate around the terra nullius proclamation and how it came to be.

We are introduced, in detail, to a pivotal figure in the colonial settlement of New South Wales and the history of the country more broadly. Ford and Clemens examine the career of Barron Field (1786-1846), the first Judge of the Supreme Court of Civil Judicature in New South Wales, who served as the highest legal authority in the colony from 1817 to 1824.

Field had established the legal precedent for terra nullius prior to Governor Bourke’s 1835 proclamation. In 1819, when he was asked to decide whether Governor Lachlan Macquarie had authority to impose taxes in the colony, he handed down a ruling that wrote the concept into the laws of the colony.

Ford and Clemens track Field’s career, in which he also made contributions to scientific research, particularly within the field of botany, and became the founder and president of Australia’s first bank, the Bank of New South Wales. Most importantly, they examine Field’s decision-making process leading up to the establishment of terra nullius as a legal principle.

But Field was not simply a legal and political man; he was also a poet. And his poetry is at the core of this book.

Terra nullius has been overturned. Now we must reverse aqua nullius and return water rights to First Nations people

Settler law and settler poetics

Barron Field in New South Wales is unlike any book that has come before it in Australian historical or literary studies. It is neither biography nor simple fact telling. Clemens and Ford have contributed a work to historical and literary study that could be seen as even more important than the archival document itself, as it offers an understanding of how the Bourke proclamation came about, what it was, what it meant, and the idea of terra nullius itself.

To illustrate the importance of Field to Australia’s foundations, Ford and Clemens – experienced academics in the fields of Romanticism, philosophy, Australian literature and poetry – have adopted a unique approach grounded in textual analysis. They offer close readings of Field’s poetry, arguing that the poems cannot be disentangled from his influence on the legal and cultural beginnings of colonial Australia. Settler law and settler poetics exist in tandem.

The project is ambitious, and innovative in its combination of historical and literary research, but the clear structuring of the book enables even the newest reader of poetry or Australian history to enter into a conversation with these fields – one that is historically relevant and culturally sensitive. The authors’ breakdown of the term terra nullius, its international and cultural history, which features early in the book, is in itself a tremendous contribution.

Ford and Clemens focus on Field’s book First Fruits of Australian Poetry (1819), which is provided in its entirety within Barron Fields in New South Wales. First Fruits was the first book of poetry printed in Australia with the forthright aim of creating an “Australian” verse. Its publication marked the beginning of a literature native to the new colony, albeit one that completely whitewashed the tens of thousands of years of oral storytelling traditions in Australia’s First Nations histories.

“Poems had certainly been written and published in New South Wales before Field,” write Ford and Clemens, “but his were the first to […] have assumed the task of originating a national poetics.”

Ford and Clemens have cleverly divided the book into three parts. The first explains the poetic and legal contexts of Barron Field’s life in the early 19th century. The book then reproduces the complete text of Field’s poetry, alongside an exploration of its themes, editions and meanings.

Finally, the authors turn to the main focus of their project. In chapters five through nine, a section titled “Readings”, Ford and Clemens offer their deep literary analysis of the poetry, along with further historical framing and explanation.

This lens of literary analysis demonstrates how much can be gained from intellectually breaking apart Field’s literary efforts. The authors treat nothing in his poetry as accidental. In their exploration of Field’s epigraphs and references to other authors, including Chaucer and Shakespeare, they explain that they

operate on the assumption that the specific reference-points invoked in [Barron Field’s] hyper citational verse are never casual: that they are, to the contrary, elements of meaning being mobilised in the service of his larger poetic aims.

The authors thus use the foundational chapters of the book as primers for the detailed arguments presented through their close readings. Readers are firmly grounded in the moment of the analysis, the historical context adding depth and relevance to the literary study. Poetry becomes a framing device to explore the constitutional powers of settler Australia. It is truly groundbreaking scholarship.

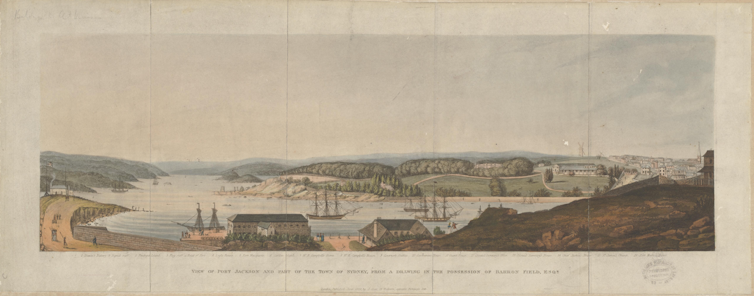

National Library of Australia.

Indigenous crime fiction is rare, but in Madukka the River Serpent systemic violence and connection to Country are explored

Topographical musings

An acquaintance of the poet William Wordsworth and other figures from the English Romantic movement, Barron Field was no stranger to poetry which cast the poet in the role of philosopher, truth maker and explorer of landscapes. Field saw himself as a purveyor of topographical musings and master of pastoral ponderings.

Such “Romantic” moments abound in Field’s work. As Ford and Clemens establish in their close readings, Field’s poetry relies on the use of botanical knowledge and meaning to establish its importance as uniquely Australian.

The longest poem Field wrote was Botany-Bay Flowers. As we see through Ford and Clemens’ critical examination, it conveys a sense of the ownership Field imagined he possessed over land and knowledge production in Australia. As the authors examine various poems from Field’s collection, we begin to see what a powerful influence this man and his words had on Australian history.

In their final section, “The Absolute Spirit of Colonisation”, Ford and Clemens make an ultimate judgement on Field as a poet, one which echoes throughout the entire book. His poetic “badness” is clear. The authors note that Field has “rarely been praised for the beauty or technical facility of his poetry”.

They also argue, however, that his poetry complicates the very nature of what is good and bad in poetry itself. Field’s work is “simultaneously insignificant and utterly significant, unoriginal and original”, because of its ethical, cultural, historical and legal ramifications.

One could not say anything “bad” about Ford and Clemens as researchers and authors in this work. Their argument for the importance of Field, despite his literary and legal shortcomings, is impressive and convincing.

Barron Field in New South Wales is a work that offers a new line of enquiry in Australian literary and historical study. It engages with colonial Australia’s place in the world: culturally, legally, and in literature. Innovative and even moving in places, it is always thought-provoking. Its reframing of our understanding of what Australia was in the time of colonial settlement suggests what we now, in more enlightened times, can be.