Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Overview

Multiple factors have affected views of China over time. In the U.S., the sense that China has handled COVID-19 poorly and is at fault for the virus’s spread certainly is related to negative opinions of the superpower, but is not the only factor driving attitudes. Rather, negative views of China were already rising prior to the pandemic. The same is true in other countries, including some of China’s neighbors, like South Korea, Japan and Australia.

Unfavorable views of China in South Korea have increased dramatically since 2017. South Korea was heavily affected by Chinese economic retribution following the country’s 2017 decision to install an American missile interceptor (THAAD). Negative views of China went up substantially in 2017 alongside this turmoil; they increased again in 2020 when, in the wake of COVID-19, unfavorable opinion went up in nearly every country Pew Research Center surveyed. But views have continued to sour, and today unfavorable views of China are at a historic high of 80%.

Japanese views of China have been broadly negative for the past decade. Negative views of China skyrocketed in the early 2000s amid myriad bilateral tensions, and for the past 20 years, Japanese views of China have always been among the most negative in Center surveys, if not the most negative. Negative views peaked at 93% in 2013, following extreme tension in the East China Sea. Very unfavorable views of China have also been particularly elevated since 2020, with around half of Japanese adults saying this describes their views of China.

While COVID-19 and resulting trade frictions led to the most negative views of China on record in Australia, unfavorable views had been ticking up since 2017. In that year, the Australian Security Intelligence Organization issued warnings about Chinese attempts to influence Australian domestic politics, resulting in new Australian laws to curb foreign interference and strong responses from China. And while views went from broadly favorable to unfavorable between 2017 and 2019, the largest year-on-year increase in negative views took place between 2019 and 2020; at the time, negative views went up 24 percentage points as trade tensions spiraled following Australia’s calls to investigate the COVID-19 virus’s origins.

% in each country with a(n) __ view of China

Note: In spring 2021 and summer 2020, the Center ran concurrent phone (solid lines in chart) and online panel (dashed lines in chart) surveys in Australia. In spring 2019 and prior to 2019, Australia surveys were conducted over the phone.

Source: Spring 2022 Global Attitudes Survey. Q5b.

PEW RESEARCH CENTER

The same pattern holds true in Canada and Sweden: Although negative views of China went up in both countries between 2019 and 2020, unfavorable views had already grown markedly in both countries amid bilateral tensions. Beyond these specific countries, unfavorable views are at or near their historic highs in many of the advanced economies we have surveyed since 2020. And, even in some emerging economies – which we have been unable to survey since 2019 due to the challenges of conducting face-to-face surveys during the pandemic – negative views of China were already commonplace three years ago. This is the case in countries like the Philippines, India and Turkey. Still, around half or more had favorable views of China in Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa when those countries were last surveyed in 2019. Views of China are also relatively more positive in Singapore, Malaysia and Israel – three countries where surveys were possible in 2022. For detailed tables on views of China, see the Appendix.

% in each country with a(n) __ view of China

Note: In spring 2020, the Center ran concurrent phone (solid lines in chart) and online panel (dashed lines in chart) surveys in the U.S. In summer 2020 and prior to 2020, U.S. surveys were conducted over the phone.

Source: Spring 2022 Global Attitudes Survey. Q5b.

PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Views of President Xi Jinping

President Xi Jinping – who is likely to be appointed to an unprecedented third term at the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party – is also seen quite negatively. He has been in power in China for the past decade, one marked by global feats like building an international space station, hosting the 2022 Winter Olympics and pouring billions of dollars into international infrastructure through the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative. But his tenure has also involved controversial island construction and militarization in the South China Sea, widespread protests in Hong Kong and human rights abuses against Uyghurs, as well as a centralization of power and elevation of himself not seen since Chairman Mao Zedong.

Much like opinion of China, views of Xi – which were already quite negative in 2014, just about a year after he took office – have become increasingly negative in recent years. In the spring of 2014, people in most places surveyed felt more negatively than positively about the new president. The primary exceptions were in emerging and developing economies in sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region. Take Uganda as an example: There, 41% were confident in Xi to do the right thing regarding world affairs, and 23% said they were not confident. Notably, 36% of Ugandans said they did not know or otherwise did not answer the question, as did roughly a third or more in 16 of the 43 countries surveyed that year. As Xi’s tenure has continued, the share who did not provide a response has decreased across some survey countries.

Views of the Chinese president turned even more negative between 2019 and 2020. By 2022, majorities in all but two advanced economies surveyed had little to no confidence in his approach to world affairs. Around four-in-ten or more in most places surveyed even say they have no confidence at all in Xi, including more than half of those in Australia, France and Sweden.

In both the U.S. and Australia, when respondents were asked an open-ended question on what they think about when they think about China, some specifically highlighted China’s leadership or Xi in particular. For example, one Australian man said, “Their leader seems to be on a path to try to control too much of the world.”

How Australians and Americans speak about President Xi in their own words

More broadly, this data from the U.S. and Australia suggests that people are generally referring to the country’s leadership or government and their actions, or its economy – not the people – when thinking about China. Views of China’s government are not automatically conflated with views of China’s people. Still, following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, discrimination against people of Chinese descent has intensified in the U.S. and across the world, raising concerns about the link between negative views of China and discrimination and harassment against people of Chinese descent.

In the following essay, we will explore global opinion toward China through the lens of five topics: China’s power and influence, its human rights policies, the country’s economy, COVID-19 and the Chinese people.

China’s influence, global threat and military

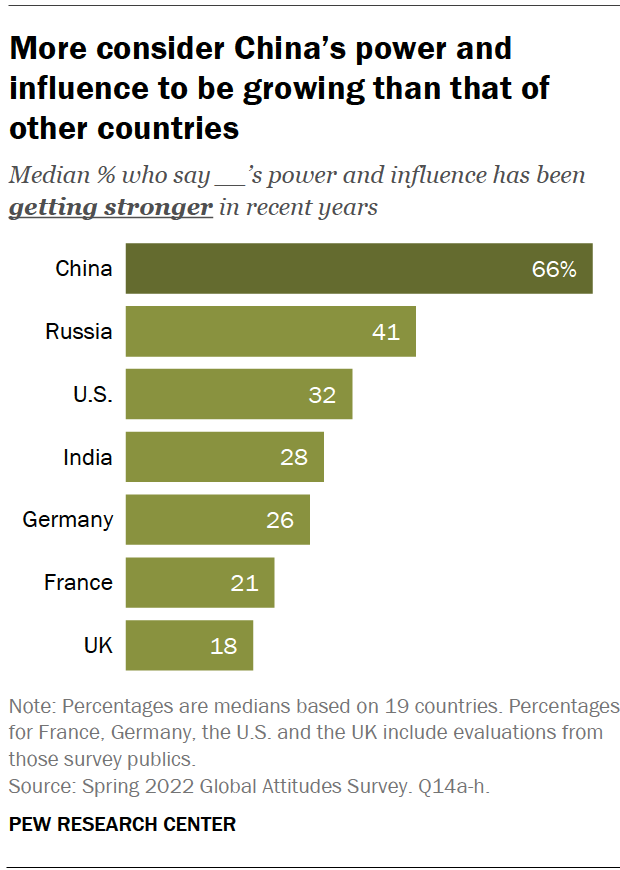

The sense that China’s power and influence on the world stage is growing is both widespread and long-held. As of this year, a median of 66% across 19 countries say that China’s influence in the world has recently been getting stronger, including seven-in-ten or more in Australia, Italy, Israel, Greece and the Netherlands. Few – a median of 12% – say China’s influence has gotten weaker. In 2018, similarly large shares said that China was playing a more important role in the world than it had 10 years prior. And the share describing China’s influence as growing was many more than said the same of Russia, India, the U.S. and Germany, among others.

In fact, when asked to directly compare China’s power on the world stage with the United States’ in 2015, roughly half or more in 24 of the 40 countries surveyed said that China was on track to replace the U.S. as the top global superpower or already had. This sense was particularly acute among some of China’s neighbors – like Australia and South Korea – as well as across most Western European countries surveyed.

How Australians and Americans speak about China’s power, influence and military in their own words

China as a perceived threat

Alongside its growing influence is a sense that China is a growing threat. Roughly half or more in South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Australia and the U.S. said China’s power and influence was a major threat to their country in 2018. But even outside these particular countries, around half or more in every country but Tunisia said China’s power and influence posed either a major or minor threat.

In the U.S., where the question about China’s power and influence as a threat was asked more recently (2022), the sense that China is a major threat increased another 19 percentage points to 67%. Similarly, the share of Americans who said limiting China’s power and influence should be a top priority grew from 32% in 2018 to 48% in 2021 (+16 points). This also made it one of the top priorities cited by Americans among 20 foreign policy goals tested. More Americans also said it was important to limit China’s power and influence than to limit the power of Russia, North Korea or Iran.

As early as 2018, the countries that stood out for seeing China as the greatest threat were the U.S., Australia, Japan and South Korea. In 2022, these countries were also among the most likely to express concerns about China’s influence in one other way: its interference in their domestic politics. In South Korea and Australia, more than half say China’s involvement in their domestic politics is a very serious problem and nearly half say the same in the U.S. In contrast, in Europe, Israel and elsewhere, around a third or fewer say China’s involvement in their own country’s politics is a very serious concern.

China’s military

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), China’s military, is the largest in the world with roughly 2.8 million members. Since he took office in 2013, Xi has made several significant military moves: He built the world’s largest navy, cultivated nuclear second-strike capability and restructured the chain of command to lead directly to himself as chairman of the Central Military Commission.

Xi also oversaw the construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea, which prompted territorial disputes with multiple neighboring countries. In 2014, when the Center first asked about the possibility of territorial disputes between China and neighboring countries leading to military conflict, there was already a great deal of concern across the Asia-Pacific region. More than eight-in-ten in the Philippines, Vietnam, Japan and South Korea said they were very or somewhat concerned about military conflict with China, as were smaller majorities in India, Malaysia and Bangladesh. Still, opinions varied somewhat about how to handle such disputes in the region. In 2015, majorities in South Korea and Vietnam favored a focus on territorial disputes over economic ties with China; a large majority in Malaysia chose the opposite. Adults in the Philippines, Japan, Indonesia and India were more split.

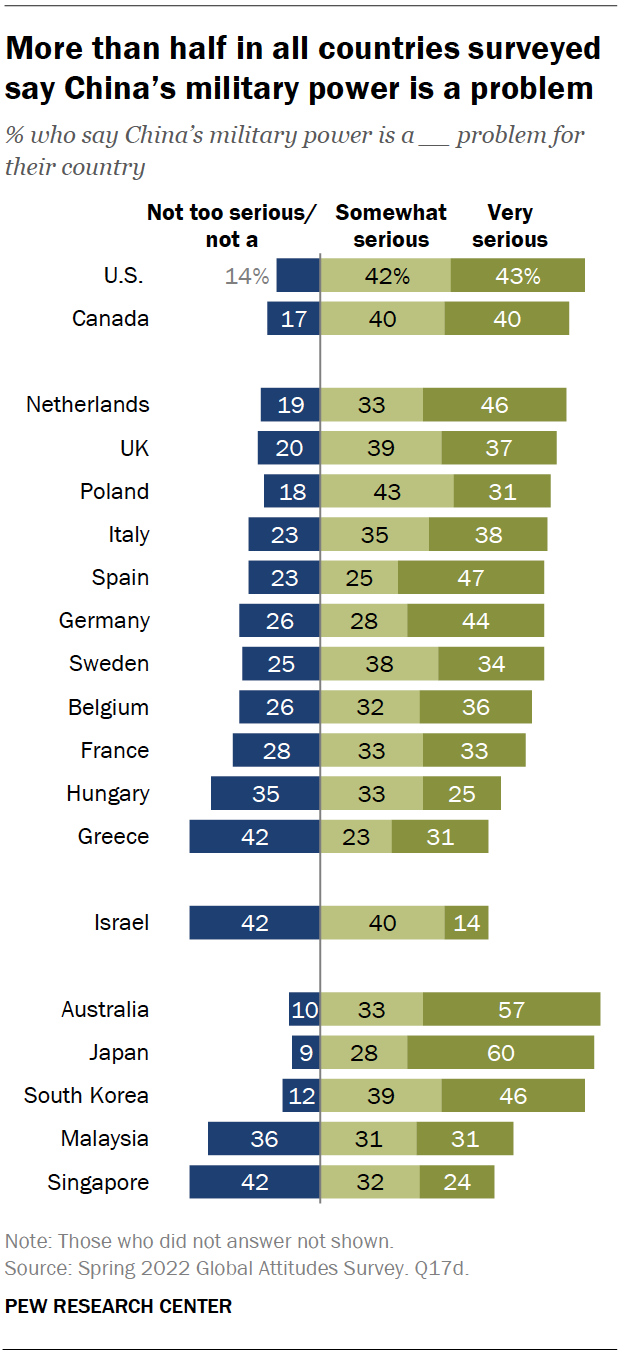

More broadly, there remain widespread concerns about China’s military. As of 2022, a median of 72% across 19 countries surveyed describe China’s military power as a serious problem, including 37% that call it a very serious problem for their country. Concerns are highest in Japan and Australia, where roughly six-in-ten say China’s military is a very serious problem. Singapore, Greece and Israel stand out as places with the least concern about China’s military.

Human rights

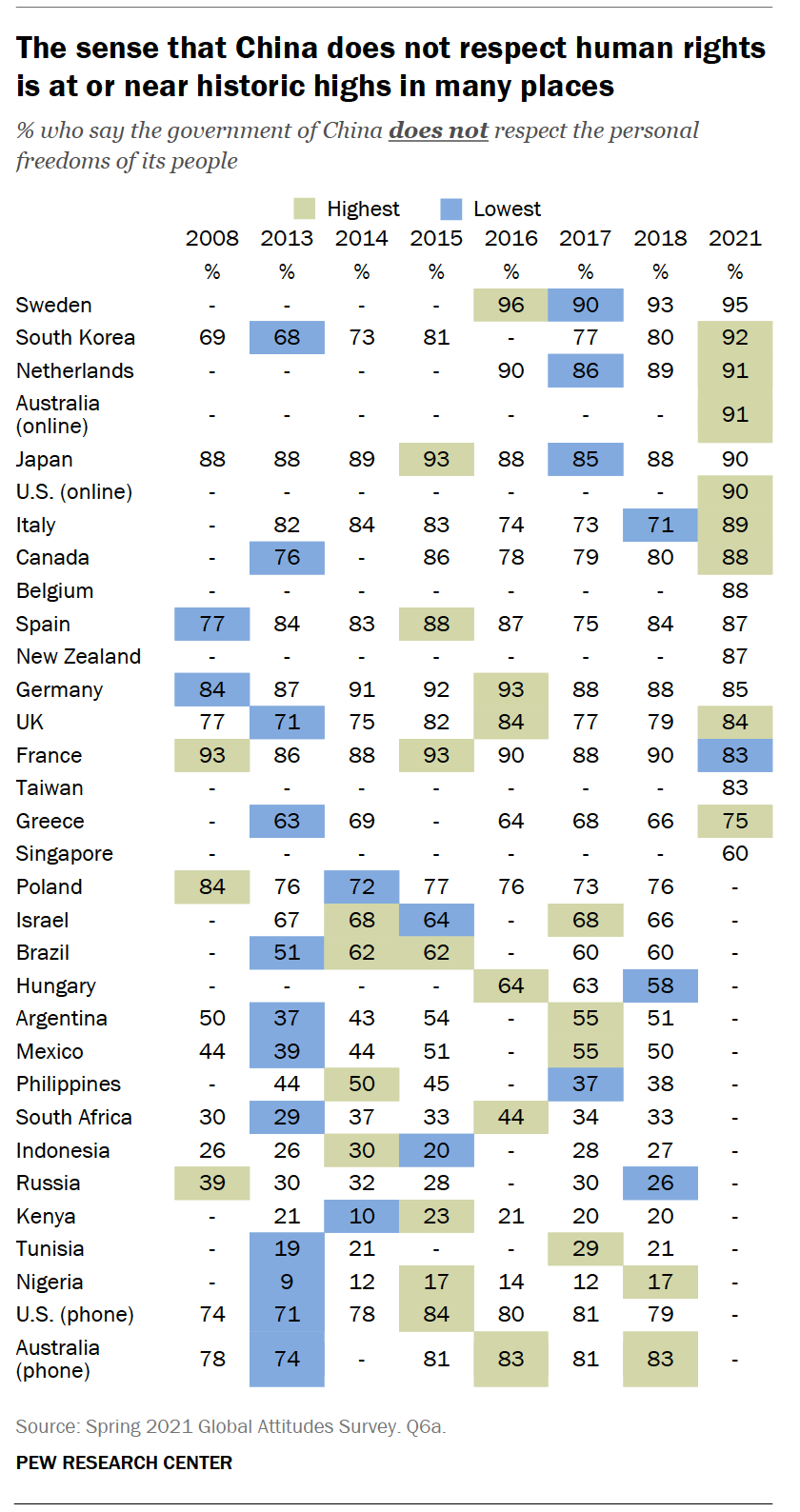

Particularly in advanced economies, China has long been seen to have a problematic human rights record. In the U.S., Canada, Australia, South Korea, Japan and every European country surveyed, a majority has consistently said that the Chinese government does not respect the personal freedoms of its people since the question was first asked in 2008. Across Latin America and Africa – regions that the Center has not been able to survey in recent years – opinion was more mixed when they were last asked in 2018. In Mexico, Brazil and Argentina, half or more said China was not respecting the personal freedoms of its people, while in South Africa, Kenya, Tunisia and Nigeria, only around a third or fewer agree. Still, across both advanced and emerging economies and in both 2018 and 2021, the sense that China does not respect the personal freedoms of its people was closely related to unfavorable views of China.

Although the sense that China did not respect the personal freedoms of its people was already high in most advanced economies in 2018, it nonetheless rose significantly again in 2021, following revelations about detention camps for Uyghurs, the U.S. declaring the situation in Xinjiang a genocide and calls to boycott the 2022 Olympics over human rights abuses, among other issues. In more than half the countries for which trends were available, this marked the largest share in history who said China didn’t respect the civil liberties of its citizens – with a majority in every public taking this stance.

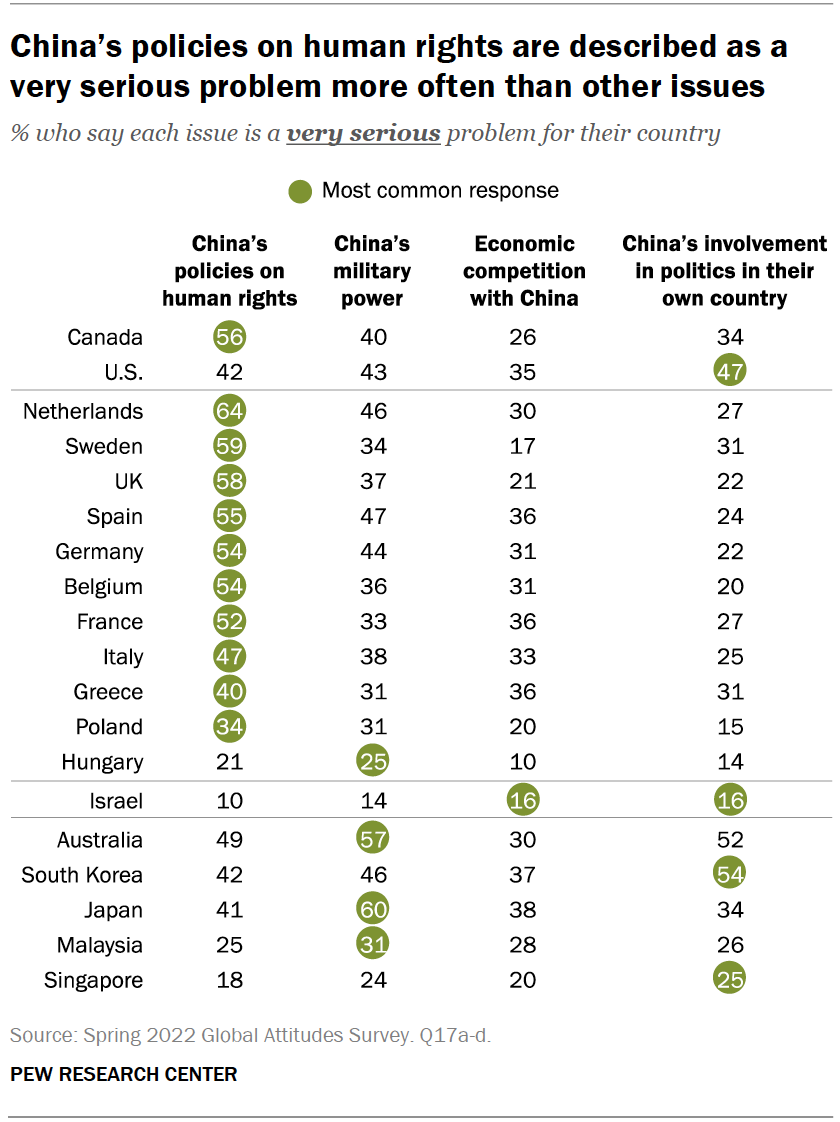

This past spring, human rights was also the issue that concerned people most – above even China’s military power, economic competition with China and China’s involvement in politics in their own country. In 10 of the 19 countries surveyed, around half or more described China’s policies on human rights as a very serious problem for their country.

These concerns, again, are linked to views of China, overall. In 18 of 19 countries surveyed, those who say China’s human rights policies are a very serious problem for their country are significantly more likely than those who are less concerned to hold an unfavorable view of China.

Human rights are also salient in both Australia and the U.S. Results of an open-ended question in 2021 asking respondents what they think about when they think about China indicated that human rights in China are top of mind. People could name anything about China, from the Great Wall to current policies and everything in between, and yet around two-in-ten in both countries mentioned China’s human rights record – as many or more than said the same of any other topic.

In the case of human rights, some Australians and Americans described their view that the Chinese government mistreats its people. Around one-in-ten in each country specifically highlighted curtailed personal freedoms, whether in the form of censorship, the inability to protest or a lack of freedom of religion. For example, one American woman said China is “a country that limits its people and curtails all their freedoms in order to maintain the domination and total control of the people.”

A small share of Australians (4%) and Americans (3%) explicitly mentioned the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghur people, an ethnic minority group in Xinjiang, a region in northwest China. A few respondents used specific terms like “genocide” – a term now applied by the U.S. government and debated in Australia – or “concentration camps” when discussing the issue. Still, in both countries, this is many more than highlighted other high-profile human rights issues like Tibet or the Falun Gong.

How Australians and Americans speak about China and human rights in their own words

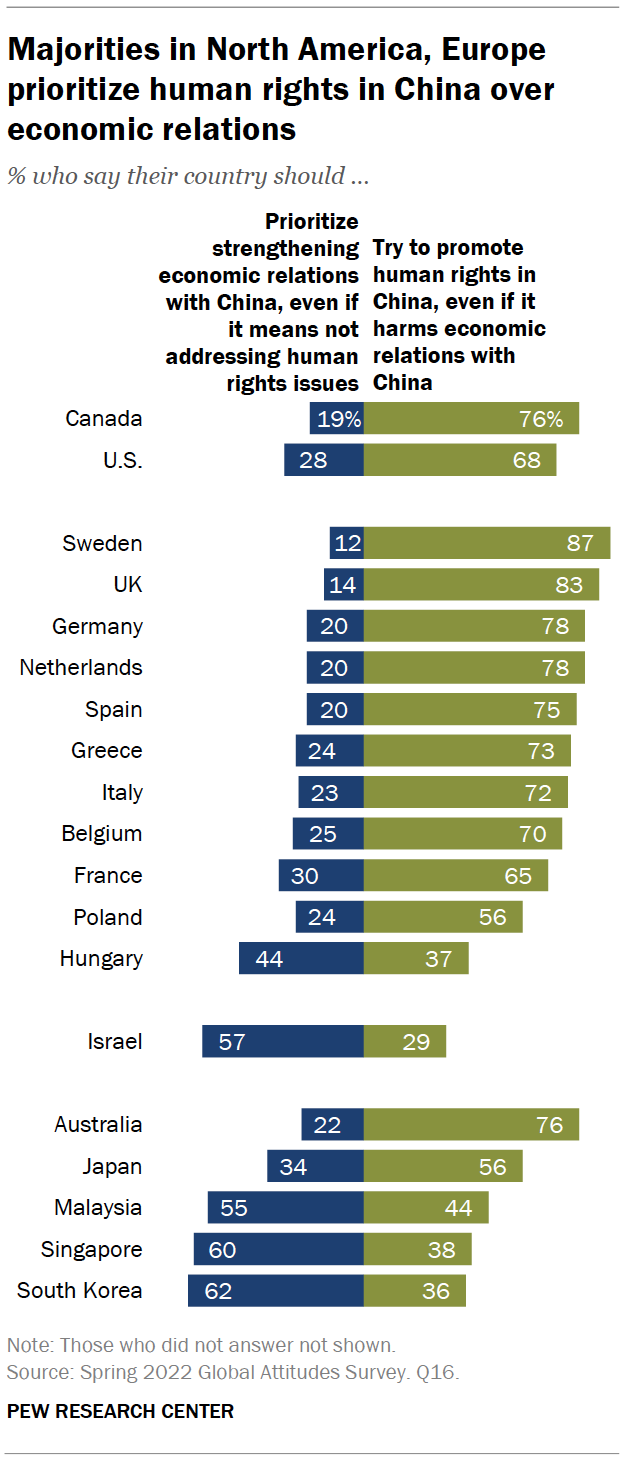

Australia and the U.S. are also two countries where a majority think that it’s more important to try and promote human rights in China, even if it harms economic relations with China. The same is true in Canada, Japan and nearly all of the European countries surveyed in 2022. But in Israel, Malaysia, Singapore and South Korea, a majority think it’s more important to prioritize strengthening economic relations with China, even if it means not addressing human rights issues.

In nearly all places surveyed, those who see China’s human rights policies as a very serious problem are more likely to favor promoting human rights regardless of economic consequences. For example, 87% of Canadians who see China’s policies as a very serious issue prioritize human rights, compared with 64% of those who show less concern. This is the case in each country surveyed except Malaysia.

In the U.S., human rights is one of the few issues related to China that is bipartisan in nature. Generally speaking, Republicans tend to have more negative views of China, to be more likely to see China as an enemy of the U.S. and to support taking a tougher approach to China than Democrats. Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party are equally as likely as Democrats and Democratic leaners to support challenging China on human rights even at economic cost, to describe China’s policies on human rights as a very serious problem for the U.S. and even to mention human rights in the open-ended question asking how people think about China. Some of this may be related to media dynamics. Results of a separate analysis find that Republicans who turn only to news outlets with right-leaning audiences and Democrats who turn only to outlets with left-leaning audiences are also more likely than others in their respective parties to say the U.S. should try to promote human rights in China, even if it harms economic relations, and that China is doing a very bad job dealing with climate change. (For more on news consumption and its relationship to views of China, see “Americans in news media ‘bubbles’ think differently about foreign policy than others.”)

Because the American surveys have recently been conducted on an online, probability panel, we are also able to look at change of opinion within individuals. Results of this analysis allow us to clearly see that changing views of China’s policies on human rights are strongly related to changing views of China. In other words, between 2020 and 2022, people who increasingly saw human rights as a serious problem for the U.S. were also more likely to have negative views of China. (For more, see “Some Americans’ views of China turned more negative after 2020, but others became more positive.”)

Economy

Despite a year-end slowdown, China’s pandemic recovery outpaced that of other major nations in 2021, and economic competition from China is seen as a serious problem among advanced economies. Those in South Korea, Japan, the U.S. and Australia are particularly concerned. About eight-in-ten or more in these four countries see economic competition from China as a serious problem in 2022, including about a third or more who say competition is a very serious problem. The survey was ongoing when Japan recorded a decline in exports to China and finished before South Korea registered a months-long trade deficit with China. Australia has seen a trade surplus with China since before the pandemic, but was hit with a series of sanctions from China in 2020.

Majorities in all but one European country surveyed also say economic competition with China was a serious problem, including at least a third in France, Greece, Spain and Italy who see it as a very serious problem. The European Union put out an official communication labeling China a “systemic rival” and “economic competitor” in 2019.

In the U.S., the Center has recorded additional concerns about the loss of jobs to China and their country’s trade deficit with China. More than eight-in-ten Americans considered both issues to be serious problems in 2021, including about half who said the loss of jobs to China was a very serious problem. Concern about the United States’ trade deficit with China has become slightly less intense over the past decade, with the share considering it a very serious problem declining from 61% in 2012 to 43%. The 2021 results were recorded before the end of the year, when the trade deficit with China increased for the first time since 2019.

How Australians and Americans speak about China and its economy in their own words

While those in advanced economies all saw economic competition from China as a serious problem in 2022, some have not always considered China’s economic growth to be bad for their countries. In North America, in 2019, about half said China’s growing economy was good for their respective countries, and roughly half or more in Australia, Japan and South Korea said the same. Among Europeans, roughly half or more in the UK, Greece, Germany and France also considered China’s economic growth as good for their country in 2014.

Most among the non-European economies surveyed in 2019 also saw China’s economic growth as a positive development for their country. Majorities in three of four Middle Eastern countries, the three African countries and two of three Latin American countries surveyed all labeled China’s growing economy as a good thing for their country. They were also inclined to see investment from China as benefiting their country: Majorities welcomed Chinese investment in Nigeria, Tunisia, Lebanon, Mexico, Israel, Kenya, South Africa and Brazil. All African countries and most Middle Eastern countries surveyed in 2019 have signed agreements with China regarding China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Mixed feelings about China’s growing economy are accompanied by a preference for closer economic ties with the U.S. than with China. In 2021, most among the advanced economies surveyed saw more value in having close economic ties with the U.S. The difference was greatest in Canada: 87% said close economic ties with the U.S. was preferable compared with just 7% who said the same about close ties with China. Large differences were also seen in Sweden, Japan and South Korea, where a close economic relationship with the U.S. led by 71 percentage points, 66 points and 58 points, respectively. Only Singaporeans were less likely to prefer ties with the U.S. than with China (-16 points) among all publics surveyed in 2021. The same was true among the countries last surveyed in 2019, most of which were emerging economies. In Australia, Canada, Japan and South Korea, the preference for economic ties with the U.S. has also increased substantially in recent years. In Australia, for example, people were around twice as likely to prefer close economic ties with China when asked in 2015, but by 2021, the relationship had fully reversed; now by a roughly two-to-one margin, people prefer close ties with the U.S. (59% vs. 31%, respectively).

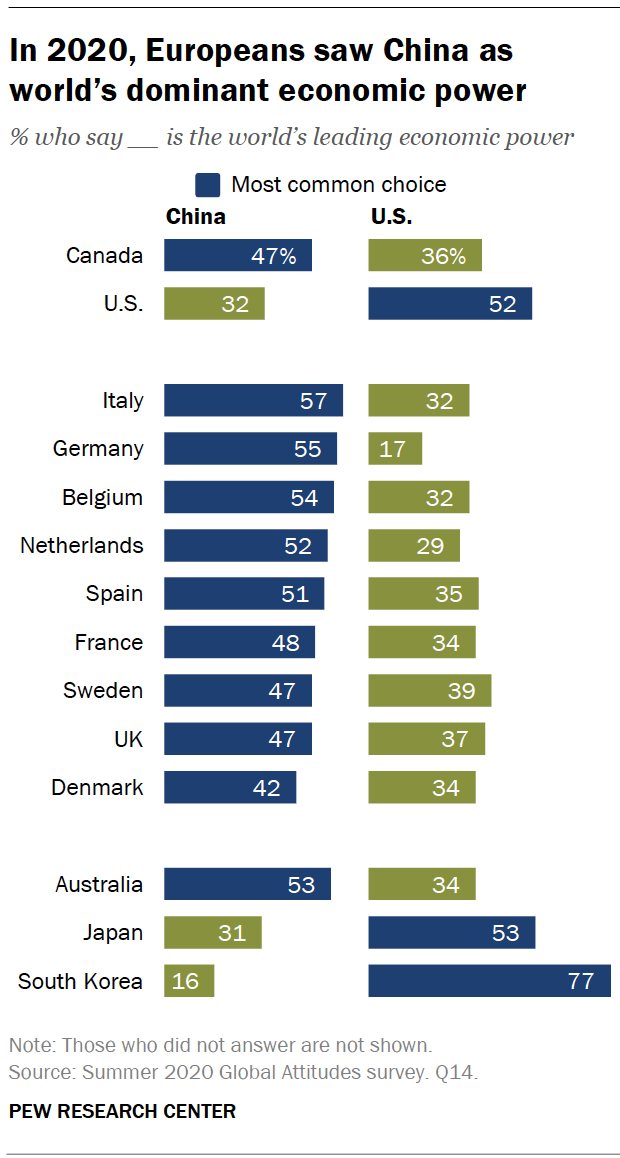

However, the preference for close economic ties with the U.S. over China in 2019 and 2021 was not necessarily because of the United States’ perceived economic strength. Instead, China was seen as the world’s leading economy in 11 of the 14 countries surveyed in 2020. In seven of nine European countries surveyed, there was a double-digit difference in the share who saw China as the top economy and the share who awarded the label to the U.S. The difference was especially large in Germany, where 55% said China was the world’s top economy and 17% said the same of the U.S. – a difference of 38 percentage points. The U.S. was more likely to be seen as the top economy by those in emerging economies, which were mostly last surveyed in 2019.

China’s economy was also relevant to Americans and Australians when asked what they think about when they think about China. Roughly a fifth in both countries mentioned topics related to China’s economy when answering the question. Some critiqued China’s economy and its manufacturing practices, such as this Australian woman who mentioned “cheap trashy goods exported to Australia.” Others brought up China’s economic system: “Trying to get the best of capitalism and communism with economic benefits of capitalism and authoritarian nature of communism,” said one American man. Still others highlighted China’s economic growth and potential or referred to it as an “economic superpower.”

COVID-19

As COVID-19 spread around the globe in early 2020, views of China also shifted dramatically in advanced economies. In Pew Research Center’s first international poll following the virus’s emergence, negative views of China increased by double digits in more than half of the countries surveyed. In Australia, for example, negative views went up 24 percentage points, from 57% who had an unfavorable view of China in 2019 to 81% who said the same in the summer of 2020. These changes are among the largest year-on-year changes in views of China visible in the Center’s nearly 20 years of polling on the topic.

Between 2019 and 2020, the share saying they had no confidence in Xi also increased precipitously in almost every country. In the U.S., for example, 50% had no confidence at all in Xi in 2019 and 77% said the same two years later. A similarly large shift also took place in Australia. Outside of Japan – where eight-in-ten already had no confidence in Xi in 2019 – views shifted around 10 points or more in every country for which there were trends available.

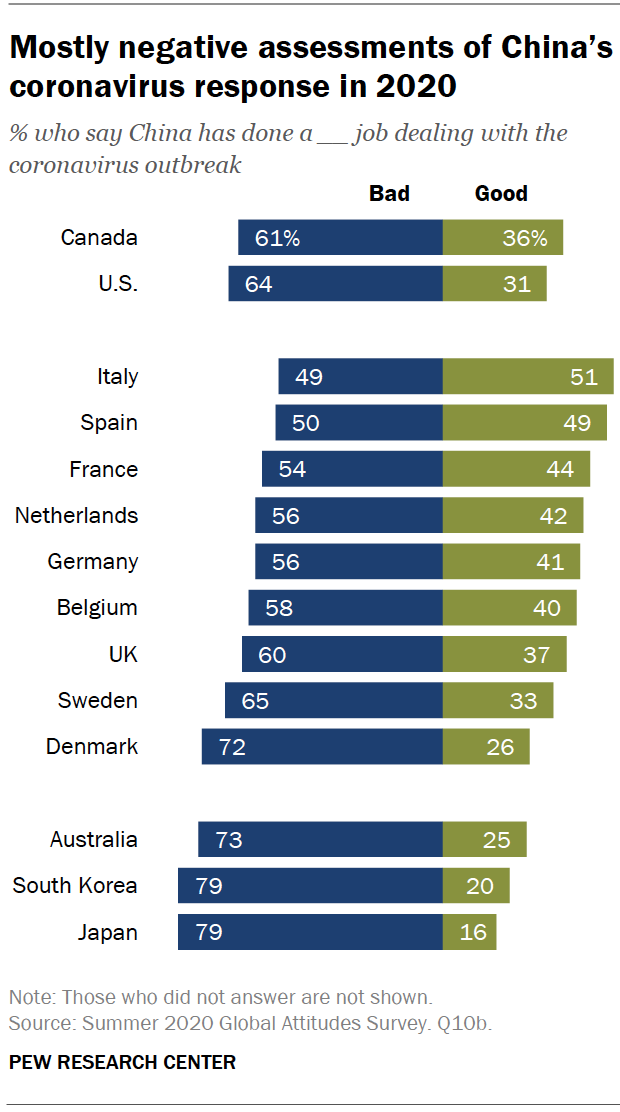

These negative views of China and the lack of confidence in Xi are closely related to the widespread sense that China did a bad job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. In 2020, around half or more in every country surveyed thought China had handled the pandemic poorly – including around two-thirds or more who said this in the U.S., Sweden, Denmark and all three countries surveyed in the Asia-Pacific region: Australia, South Korea and Japan.

Notably, assessments of China’s handling of the coronavirus outbreak were generally much more negative than those of institutions like the World Health Organization and the EU and evaluations of their own country’s response. Still, in most countries, more thought China was doing a good job than said the same of the U.S.

An open-ended survey question asked in both Australia and the U.S. in 2021 revealed that when people think about China in the context of COVID-19, much of the focus is on how it originated. Respondents mentioned Wuhan, wet markets and even theories about China purposefully creating the virus in a lab. Others focused on a lack of transparency that caused the pandemic, such as one American woman who said “… they allowed the virus to spread globally by allowing citizens to fly out of their country but restricted travel within their own country,” or another woman who noted “… they knew about coronavirus well before they let anyone else know and caused much of this spread here.” In fact, to the degree that respondents mentioned how China combated the outbreak once it started, some complimented its relative success – even if it came with authoritarian measures or excesses (a sentiment some held even prior to the Shanghai lockdown in 2022).

How Australians and Americans speak about China and COVID-19 in their own words

In the U.S., adults were specifically asked about whether the Chinese government’s initial handling of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan was to blame for the global spread of the virus; 78% said the country deserved a great deal or a fair amount of the blame. Half of Americans further thought that the U.S. should hold China responsible for the role it played in the outbreak of the coronavirus, even if it meant worsening economic relations. Still, 38% thought the U.S. should prioritize strong U.S.-China relations, even if it meant overlooking any role China played in the outbreak.

While views of China’s handling of the pandemic improved somewhat by the summer of 2021 – especially in Europe – they nonetheless still lagged behind evaluations of most other organizations and countries (the notable exception being the U.S.).

People

Data from the U.S. and Australia suggest that people are generally referring to the country’s government or the economy – not the people – when thinking about China. When asked what comes to mind when thinking about China, just 6% in Australia and 3% in the U.S. brought up people. In comparison, about a fifth or more in both the U.S. and Australia mentioned China’s political system or economy.

How Australians and Americans speak about Chinese people in their own words

Responses showed that views of China’s government were not automatically conflated with views of China’s people. Some made sure to contrast their positive views of China’s people with their negative views of the country’s government, such as this Australian woman who said, “The people themselves are lovely, but the government is power hungry.” Others specified that the negative views they expressed applied only to the government. “I’m concerned about the Chinese government but I don’t have a problem with their people,” said one American woman. The Center found a similar distinction between a country’s people and government with American views of Israel.

Others had only positive things to say about Chinese people. An American man described China’s people as “warm, kind, intelligent, smart, hardworking,” and an Australian woman said, “They are strongly family-orientated and they at the same time don’t go overboard with the number of kids. They are hard workers.” Still, some made negative characterizations, using adjectives like “barbaric” or “dirty” or mentioning stereotypes: For example, an American woman referred to “dog and cat consumers” when discussing China.

Older data shed some additional light on what traits Americans associate with Chinese people. In 2012, Americans were asked whether certain attributes described the Chinese people, and majorities described the Chinese people using positive attributes like hardworking, inventive and modern. Substantial minorities also said honesty, tolerance or generosity described the people. Negative attributes like competitive and nationalistic were also widely associated with the Chinese people, while roughly a quarter or more said aggressiveness, greed, arrogance, selfishness, rudeness and violence applied to the Chinese people.

Japanese people were also asked about the same stereotypes in 2016 and generally had few positive things to say about the Chinese, with majorities describing them as arrogant, nationalistic and violent. Even when it comes to the trait of being hardworking, only a minority of Japanese said it described Chinese people – down significantly between 2016 and 2006.

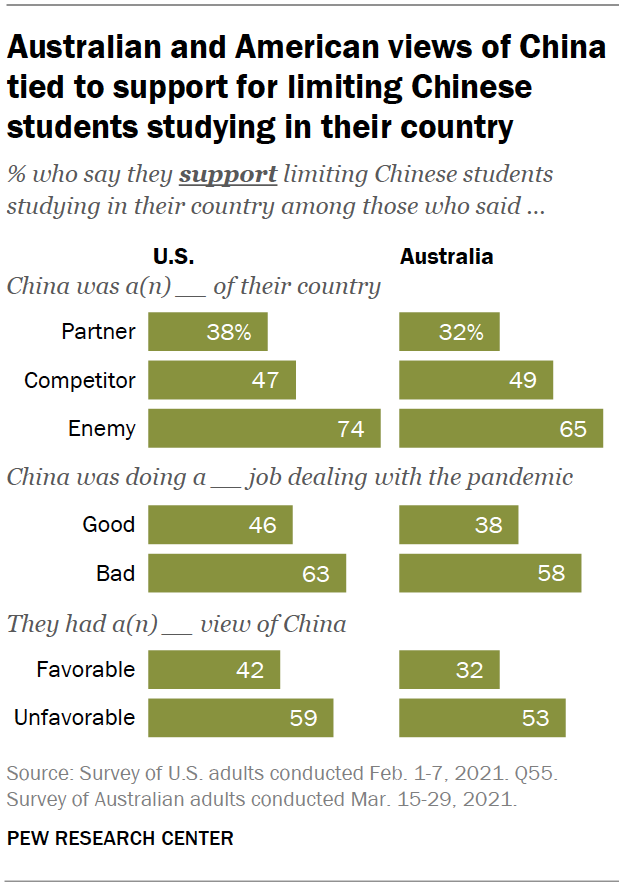

Though Americans and Australians mostly had the government or economy in mind when thinking about China, the Center nonetheless found that those with unfavorable views of China were about 20 percentage points more likely to support restricting Chinese students studying in the U.S. or Australia. In 2021, 55% in the U.S. and 50% in Australia supported limiting Chinese students studying in their country. Those holding unfavorable views of China were significantly more likely than those with favorable views to hold this opinion. Likewise, those who saw China as an enemy of their country were more likely to support limits on Chinese students than those who saw China as a partner or competitor; those who thought China was doing a bad job handling the pandemic were more likely than those who believed China was doing a good job to support such limits.

Support for restricting Chinese students studying in the country was also related to age and partisanship. Australians and Americans ages 18 to 29 were less likely than their older counterparts to support limits on Chinese students. Republicans in the U.S. and supporters of the then-governing center-right Liberal National Coalition in Australia were more likely than Democrats and nonsupporters of The Coalition, respectively, to favor limitations on the number of Chinese students attending their country’s college or universities.

In 2021, some in the U.S. saw a connection between racist political rhetoric about China and a rise in violence against Asian Americans. Among Asian Americans who said violence against Asians in the U.S. was increasing, a fifth attributed the increased violence to former President Donald Trump’s language about China as the source of the pandemic, such as his racist references to “kung flu” or the “Chinese flu.”

About this essay

This essay was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. It is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of a number of individuals and experts at Pew Research Center. Results presented in this data essay are drawn from nationally representative surveys conducted over the past 20 years in more than 60 countries. For detailed tables on views of China, see the Appendix.