What makes us human? What (if anything) sets us apart from all other creatures? Ever since Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, the answer to these questions has pointed us back to our own animal nature.

Yet the idea that, in one way or another, our humanity is entangled with the non-human has a much longer and more venerable history. In the West, it goes all the way back to Classical antiquity – to Greek and Roman views about humans and animals.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322) first argued the human stands out from all other animals through the presence of logos (“speech” but also “reason”). Numerous Greek and Roman thinkers engaged in similar attempts to name what, exactly, sets humans apart.

Who or what is man? The arguments these philosophers came up with verged from the obscure to the outright bizarre: The human alone has the capacity to have sex at all seasons and well into old age; the human alone can sit comfortably on his hip bones; the human alone has hands that can build altars to the gods and craft divine statues. No observation seemed too far-fetched or outlandish.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

And yet, above all, the argument that animals lack logos continued to resonate. In classical antiquity it became powerful enough to coin the very word for animals in ancient Greek: ta aloga – “those without logos”.

This position was taken up by the philosophical school of the Stoics and from there came to influence Christianity, with its view of man made in the image of God.

The idea of an insurmountable gap between humans and other animals soon became the dominant paradigm, informing, for instance, the 18th century naturalist Carl Linnaeus’s influential classification of the human as homo sapiens (literally: the “wise”, or “rational man”).

The practical implications of this idea cannot be underestimated. What has been termed “the moral status of animals” – the question of whether they should be included in considerations of justice – has traditionally been linked to the question of whether they have logos. Because animals differ from humans in lacking both speech and reason (so this line of argument goes) they cannot themselves formulate moral positions. Therefore, they do not warrant inclusion in our moral considerations, or at least not in the same way as humans.

Increasingly, of course, as many contemporary philosophers have pointed out, this idea seems too simple.

New research in the behavioural sciences illustrates the at times astonishing capacities of certain animals: crows and otters using tools to crack open nuts or shells to make their contents available for consumption; octopuses lifting the lids to their tanks and successfully escaping to the ocean through pipes; bees optimising their flight path on repeated trips to a food source.

Victor1153/shutterstock

But there is, in fact, a considerable body of evidence from the ancient Greek and Roman worlds showcasing the complex behaviours of different kinds of animals.

Ancient authors like Pliny, Plutarch, Oppian, Aelian, Porphyry, Athenaeus and others have dedicated whole books or treatises to this topic, pushing back on the notion of animals as merely “dumb beasts”.

Their views anticipated the modern debate by attributing animals not only with forms of reason; they also highlighted their capacity to suffer, to feel pain and to feel empathy towards each other and, occasionally, even towards members of the human species.

Then there are the human-animal hybrid creatures of the Greek and Roman myths (more on this later) – the Sirens, the Sphinx, the Minotaur. All combine the body parts of human and animal. Individually and collectively they thus raise a fundamental yet potentially disturbing question: what if we are really, in part at least, animal?

Ancient animal-smarts

In On the Nature of Animals (late second/early third century CE), Aelian, a Roman author writing in Greek, described fish that helped their unfortunate mates when caught at sea, setting their backs against the trapped creature and “pushing with all their might to try to stop him from being hauled in”.

He wrote, too, of dolphins that helped fisher-folk, pressing the fish in “on all sides” so they couldn’t escape. In return, they were rewarded for their labours by a share of the catch.

He celebrated the clever design of beehives, observing:

The first thing that they construct are the chambers of their kings, and they are spacious and above all the rest. Round them they put a barrier, as it were a wall or fence, thereby also enhancing their importance of the royal dwelling.

By parading animal-smarts in action these examples – of which there are hundreds – astonish, inform, and entertain at the same time – similar perhaps to the ubiquitous reels showing animals doing amazing things circulating in modern social media.

Modern ethological studies variously observe animal behaviours which reverberate with Aelian’s examples.

Pairs of rabbit fish have been shown to cooperate, with one partner standing on guard protecting the other one while feeding. Honeybees indeed build bigger cells for their queen that are set apart at the bottom of the hive separated by thicker walls. And bottlenose dolphins have been found to cooperate with humans in their efforts to capture fish.

Anita Kainrath/shutterstock

While not all of the ancient anecdotal evidence is confirmed by modern research, the overall thrust is clear: it deserves to be taken seriously and is part of the ancient conversation of what makes us human.

The power of storytelling

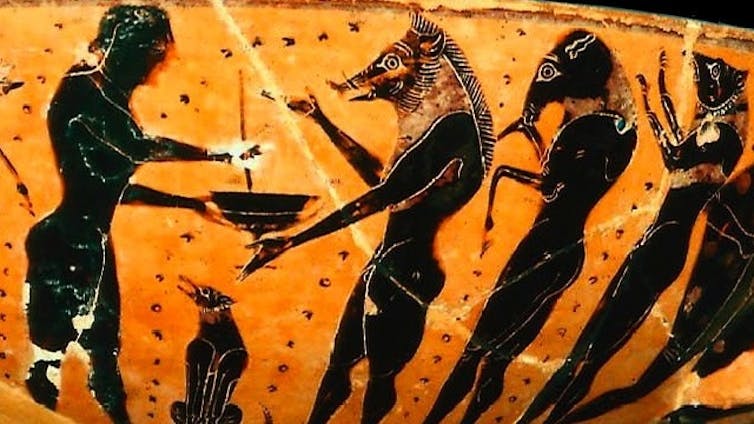

Some Greek and Roman thinkers resorted to the medium of storytelling to articulate views that are essentially philosophical in nature. The Greek philosopher Plutarch’s treatise Beasts are Rational draws on the famous story from Homer’s Odyssey in which some of Odysseus’ comrades are turned into pigs by the sorceress Circe.

Guide to the Classics: Homer’s Odyssey

Odysseus is eventually able to convince the sorceress to turn them back into human beings. In Plutarch’s rendering of the story he returns to Circe’s island to check whether there are any other Greeks turned animal – and finds a pig named Gryllus (“Grunter”).

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

Things take a turn for the unexpected when Grunter declines Odysseus’ offer of help. The reason? He prefers his animal to his human existence.

Grunter sets out to make an impassioned, highly rational case, arguing all animals in one form or another, have reason. Individual species differ from each other merely in the extent of and kind of reason. And, yes, this includes even those animals that have come to serve as the epitome of dumbness: sheep and the ass.

“Please note,” he adds, “that cases of dullness and stupidity in some animals are demonstrated by the cleverness and sharpness of others – as when you compare an ass and a sheep with a fox or a wolf or a bee.”

Grunter is not afraid to push things even further: Don’t individual humans, too, differ from each other in cleverness and wit? Long before the arrival of evolutionary theory, the pig here points towards a gradual view of how certain features, skills, and capacities map onto a continuum of all living creatures (the human included). The implied conclusion: there is no insurmountable gap between the human and other animals.

Grunter’s views are supported by others such as the speaking rooster of Lucian’s The Dream or the Cock (second century CE). Claiming to be the latest in a long line of previous incarnations that include (brace yourself) – the philosopher Pythagoras, the Cynic philosopher Crates, the Trojan hero Euphorbus, the Greek courtesan Aspasia, and several animals – this rooster-philosopher, too, prefers his animal to his human existence.

Animals, the rooster argues, are content with the basics; humans, by contrast, over-complicate things because they can’t get enough and greedily strive for ever more.

Guide to the classics: Darwin’s The Descent of Man 150 years on — sex, race and our ‘lowly’ ape ancestry

Myths and hybrid monsters

Myth is arguably the most influential genre of ancient storytelling. A set of malleable tales of great age and importance, myth constitutes a world apart, a medium just far enough removed from the intricacies (and banalities) of everyday life to allow for the exploration of fundamental questions concerning the human condition. And Greek myths often explore human entanglements with non-human animals in ways that reference the philosophical debate.

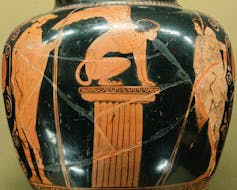

The mythical figure of the Minotaur for example – a hybrid creature sporting the head of a bull and the body of a human male – does not seem to adhere to the norms and conventions applying to either of his composite identities.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

His insatiable appetite for young humans sets him apart from accepted behaviour for both humans and cattle alike, identifying him as monstrous.

But what are monsters for?

This question also applies to another famous hybrid beast of the ancient world: the Theban sphinx. Perched high outside the gates of the city of Thebes, in the region of Boeotia in central Greece, this creature (half woman, half lion, often endowed with an extra set of wings) challenges all wishing to enter with the following riddle:

What is that which has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?

Many try and fail to name the right answer, paying for it with their lives. Until Oedipus comes along. He gives the correct answer and thus busts the beast, which dutifully throws itself to death.

The creature in the riddle is, of course, the human: man first crawls on four legs, then walks on two, until in old age when a walking stick may serve as a third “leg”. And yet despite his clever wit, Oedipus is ultimately unable to use reason to his and the city’s advantage (a situation explored in depth in Sophocles’ famous tragedy Oedipus the King).

What is the point of the riddle of the Sphinx? This story poses the human as a question but also illustrates the limits of logos in gaining self-understanding. Oedipus can solve the beast’s riddle; yet the riddle of his own humanity remains unresolved until it is too late. Here, the monstrous figure holds up a mirror for the human to recognise himself.

Speaking animals

Logos (in the sense of speech) also features prominently in the intervention of another iconic creature from classical antiquity: Xanthus, Achilles’ speaking horse.

On the battlefields of Troy (featured in Homer’s Iliad) Xanthus reminds Achilles of his imminent death. In this way the horse seems to tease all those thinkers (ancient and modern) who have argued the human stands out from all other animals in his capacity to speak in complex sentences.

Guide to the classics: Homer’s Iliad

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

Xanthus’s voice resonates with that of numerous other speaking animals populating Greek and Roman literature, including the gnat of Pseudo-Virgil’s Culex, the speaking eel in Oppian’s didactic poem On Fishing, and the whole chorus of animals speaking to us in ancient fables.

Individually and as a group they raise a question: what if animals could speak to us in human language? What would they have to say to those humans prepared to listen?

As it turns out in these stories, often nothing too flattering. In classical antiquity, speaking animals often use their special position to question or examine the human condition.

Xanthus is a case in point. By reminding Achilles he is fated to die at Troy, the speaking horse reminds the Greek hero of an important aspect of the human condition: his own mortality and the fact that he, too, is ultimately subject to powers beyond human control.

The political bee

In Greek and Roman accounts of honeybee politics we find a peculiar human habit with a surprisingly long history: the attribution of political qualities to honeybees.

When we distinguish a “queen bee” from “workers” we are continuing a tradition that goes back to the ancient world (and possibly beyond). Aristotle names honeybees among the zoa politika (the “political animals”) – a category that includes wasps, ants, cranes, and, above all, the human.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-SA

He and others then set out to explore the intricacies of honeybee society. The ancient Greeks and Romans traditionally considered honeybees to inhabit a monarchy. In line with the gender realities of the ancient world, they imagined this monarchy to be led by a king or male leader.

Does the bee monarch have a stinger? If not, how does he assert his power and leadership? And what does the presence of the obviously unproductive drones in the hive say about the distribution of labour in a community? These are the kind of questions that resonated among Greek and Roman thinkers.

Honeybee society thus provided a perfect microcosm to study a set of questions that concerned human politics and society. The Roman philosopher Seneca, for instance, asserted that the bee monarch leads by clementia (mercy or mildness) – a form of leadership he found woefully lacking in contemporary Roman society.

Meat and man

So far we have seen animals mostly playing a symbolic role in Graeco-Roman storytelling. There is also a very real way in which human and animal bodies come to merge: through the human consumption of meat.

The ancient Greeks and Romans were ardent meat-eaters. Indeed meat-eating became a status symbol closely linked to the articulation of masculine identities.

In classical Greece the male citizen received his equal share of meat after communal religious sacrifices carried out by the polis (“city-state”). Meat eating also features prominently in several anecdotes about successful ancient Greek athletes who toned their extraordinary bodies through the consumption of ridiculous amounts of meat.

One of them – a boxer named Theagenes – even claimed to have gobbled up an entire oxen in one sitting. Another one – Milo of Croton – apparently gained his extraordinary strength by carrying a heifer on his back as a young man until both he and the heifer had grown up.

Meanwhile at Rome, the elites sought to outdo each other by hosting ever more lavish dinner parties typically featuring one or several meat dishes. More often than not this involved attempts to serve a bigger or larger quantity of boar than their peers. Roman sumptuary laws eventually sought to control the worst excesses – albeit with limited success.

The shearwaters of Diomedea

The real also blends into the imaginary in the story of a special kind of bird. The Scopoli Shearwater (Calonectris Diomedea) is a species common to the Adriatic and other parts of the Mediterranean Sea. One of its outstanding features is that its cries resemble that of a wailing baby. These birds feed on small fish, crustaceans, squid, and zooplankton and are both migratory and pelagic.

The stories told about these birds by several ancient authors bring us to what is perhaps the most momentous way of exploring the human-animal boundary: the idea that in the realm of myth, at least, some humans, under certain conditions, could turn into animals and back again (metamorphosis).

D.serra1/shutterstock

According to Aelian, some shearwaters residing on a rocky, otherwise uninhabited island in the Mediterranean Sea showed puzzling behaviour. They duly ignored all non-Greeks arriving on their island. Yet if Greek people reached their shores they welcomed them with stretched wings, even settling down on their laps as if for a joint meal.

What motivated this curious behaviour?

The backstory explains that the birds were once human. They were the comrades of Diomedes, king of Argos, one of the Greeks fighting at Troy, who is said to have died on the same island now inhabited by the birds. Apparently, upon his death, his friends grieved so heavily the goddess Aphrodite turned them into birds – their cries forever bemoaning the passing of their comrade.

On the face of it this story is merely another example of a myth explaining an outstanding feature in nature (the birds’ endearing human-like cry). Yet there is more to the birds’ curious behaviour than meets the eye. In discriminating between Greeks and non-Greeks the birds seem to recall not only their former humanity but specifically their Greekness; they even seem to engage in the central Greek practice of extending friendship to guests (xenia) and the sharing of food.

In doing so they illustrate a central point of ancient (and many modern) tales of metamorphosis: even though the body may turn animal, the mind remains human. As the seat of logos it contains our humanity while the body adds little, if anything, of substance.

As such, rather than imagining what the world looks like from the point of view of a non-human creature, tales of metamorphosis ultimately come to reaffirm the view that the human stands apart from all other animals.

And so?

Cambridge University Press

In the myth of the Minotaur, the Greek hero Theseus eventually enters the labyrinth in which the Minotaur is confined, tracking him down, and slaying him. With the help of a thread given to him by Ariadne, he finds his way back out to tell the tale.

But trying to make sense of the Minotaur and other iconic creatures from the ancient world leads us down a rabbit hole into a place of blurred boundaries: where the human emerges as a contested figure somewhere in the space between mind and body, human and animal parts.

In the end, then, there is no hard and fast boundary separating us from all other creatures – notwithstanding all efforts to dress ourselves up as different.

Rather, it is the negotiations between different facets of our identity which make us human