More than half (54.7%) of women in New Zealand have experienced violence or abuse by an intimate partner in their lifetime. As we show in our new research, this increases their risk of developing a mental health disorder almost three times (2.8 times) and a chronic physical illness almost twice (1.5 times).

More than 1,400 women from a nationally representative sample from the 2019 New Zealand family violence study He Koiora Matapopore told us about their experiences of intimate partner violence and their health. We asked them about chronic health problems (heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes and asthma) as well as mental health conditions (depression, anxiety or substance abuse).

We also asked women about their lifetime experiences of physical violence, sexual violence, psychological abuse, controlling behaviour and economic abuse by any partner. We used questions from the World Health Organization multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women – the international gold standard for measuring the prevalence of violence against women.

In addition to the physical and mental health problems described above, women who had experienced any of these types of intimate partner violence had increased risk of poor general health (2 times more likely), recent pain or discomfort (1.8 times more likely) and recent healthcare consultations (1.3 times more likely).

Physical and sexual violence hurts people, but it wasn’t just this type of violence that was associated with increased health problems. Women who experienced psychological abuse, controlling behaviours and economic abuse also had greater risk of adverse health outcomes.

Domestic violence isn’t about just physical violence – and state laws are beginning to recognize that

Partner violence increases health risks

It is common for women to experience multiple types of intimate partner violence. One in five women reported experiencing three or more types of partner abuse, and these women had a much higher risk of poor health.

More than one in ten (11%) had experienced four or more types of abuse and these women were over four times more likely to have a mental health condition and double the risk of chronic health problems, compared with women who had not experienced violence by a partner.

Our study reports on lifetime rates of intimate partner violence, but new and recurring violence keeps happening. There were 175,573 family harm investigations recorded by police in the year to June 2022. People who require police intervention may have even worse health than the women we talked to.

Our findings provide an even stronger rationale for supporting and strengthening strategies to counter the national scourge of intimate partner violence.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the impacts of gender-based violence worse

Our recommendations

The Manatū Hauora/Ministry of Health’s violence intervention programme needs to receive more attention and funding, and Te Whatu Ora/Health New Zealand needs to prioritise implementation.

The programme has developed an infrastructure to provide evidence-based strategies for family violence assessments and intervention. However, it is not well embedded in the health system and needs strong policy, leadership and resourcing to achieve its potential. It also needs to be supported by the health infrastructure to put it into practice.

Fundamentally, healthcare professionals need to recognise violence experience as a health issue. Effective, regular training about the prevalence and health consequences of intimate partner violence is essential to enable healthcare professionals to help women who have experienced abuse.

This education needs to be embedded in core practitioner training. Universities need to step up to ensure healthcare professionals have the knowledge and skills they need to address the issue.

A new national plan aims to end violence against women and children ‘in one generation’. Can it succeed?

Healing and prevention

We also need to expand our suite of responses. These must include referral options to help women in times of acute danger and crisis, but also to support long-term recovery and healing from abuse.

Increasing capacity to support healing is one of the key shifts recommended by Te Aorerekura, the national strategy to eliminate family and sexual violence.

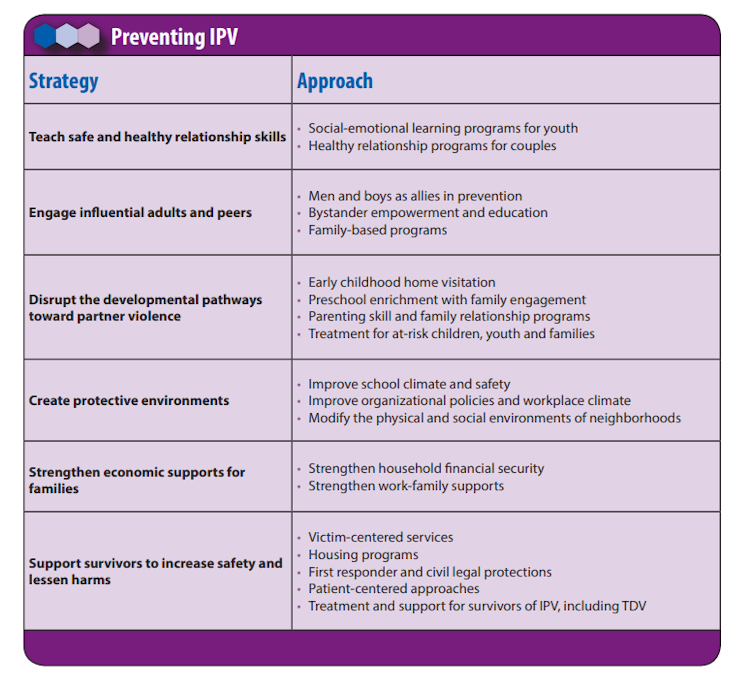

We need to invest in evidence-based prevention strategies and ensure they have comprehensive and equitable coverage across the nation. Prevention is one of the recommendations from Te Aorerekura, but the effectiveness of local efforts could get a significant boost if they tapped into international evidence-based prevention strategies.

CDC ATSDR, CC BY-ND

Prevention initiatives need to be brave enough to address unhealthy forms of masculinity and discrimination against women and girls. Targeting men’s and boys’ understanding of power and control in relationships and engaging them in violence prevention is both essential and possible.

Developing and sustaining evidence-based prevention and response programmes to address intimate partner violence will require long-term investment and implementation. However, we are already paying for the health and social costs of intimate partner violence. This money could instead be spent fixing it.

Funding work that leads to healthy, respectful relationships could be the “win” we are all looking for. It would yield multiple benefits, including a healthier population, fewer incarcerations and criminal justice problems, better educational outcomes and a more economically productive society.

Our study also looked at men’s experiences of intimate partner violence. It

showed that while the experience can affect men’s health, it did not consistently contribute to men’s poor health at the population level. However, men who experience partner abuse still need care and support options.