Misinformation in Indonesia has spread extensively and pervaded areas such as politics, religion and health as the 2024 General Election draws closer.

In response, news organisations and civil society organisations in Indonesia have initiated a digital fact-checking movement as an effort to tackle misinformation. Two organisations that become the pioneers of such a movement are the Indonesian Cyber Media Association (AMSI) and the Alliance of Independent Journalists (Aliansi Jurnalis Independen/AJI), with support from the Google News Initiative.

The three organisations have established cekfakta.com, a web-based platform through which 25 Indonesian press institutions collaboratively share fact-checking results. Through this movement, they publish digital content that aims to track and correct other content suspected of carrying false information.

News organisations have built networks locally and internationally to enhance fact-checking capabilities. One of the driving factors behind the fact-checking movement in Indonesia has been the Google News Initiative. The organisation has provided US$33 million in funding to support digital literacy and misinformation-busting program in the Asia Pacific. More than 1,000 media partners across 32 countries, including Indonesia, have joined the movement.

This massive digital fact-checking initiative has been a significant step to take to protect the public from misinformation.

However, in our latest research, we, a team from department of digital journalism at Multimedia Nusantara University, have found that the initiative still lacks public attention, at least in part because text is the dominant media of the fact checks. A more dominant role for visual elements in fact-checking content may make them more engaging and appealing to the public.

People want more visual appearance

With support from the Indonesian Cyber Media Association and Google News Initiative, we asked 1,596 audiences representing regions across Indonesia in 2022 about their preferences for the format of fact-checks produced by Indonesian journalists.

In the early stages of the research, we identified seven formats of fact-checks produced by Indonesian journalists. They are texts with photos, static infographics, debunking statements from political candidates, Instagram live, videos with background music, videos with a narrator and videos with a reporter.

We measured the audiences’ preferences of each format using four variables: how familiar is the content, how frequently they see the content, how much they like it and how likely they will use it.

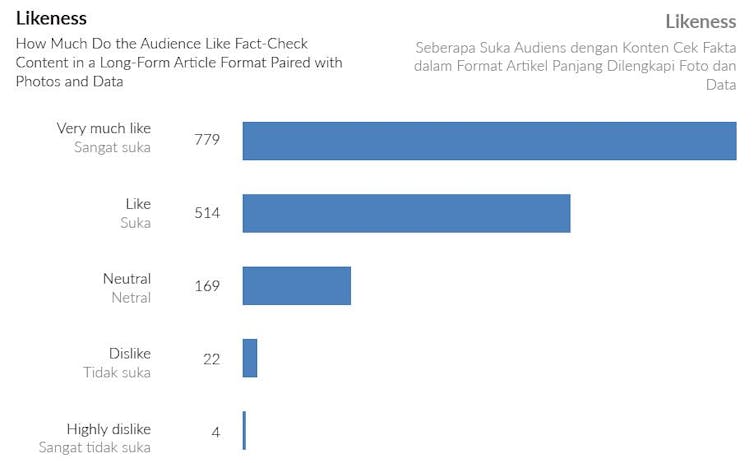

One of the interesting results is that while 49% find that text fact-checks are useful, they do not actually like them. Audiences in Indonesia prefer the fact-check formats dominated by visual elements, either videos or photos.

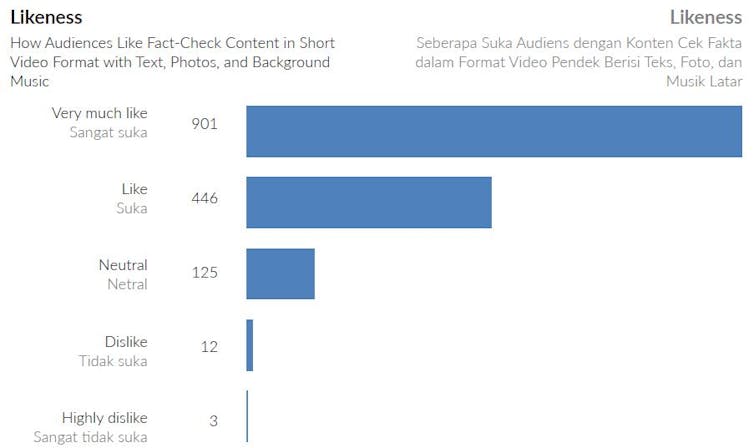

As many as 901 respondents (60.6%) revealed that they “very much like” fact-checking content in the form of short videos accompanied by text, photos and background music.

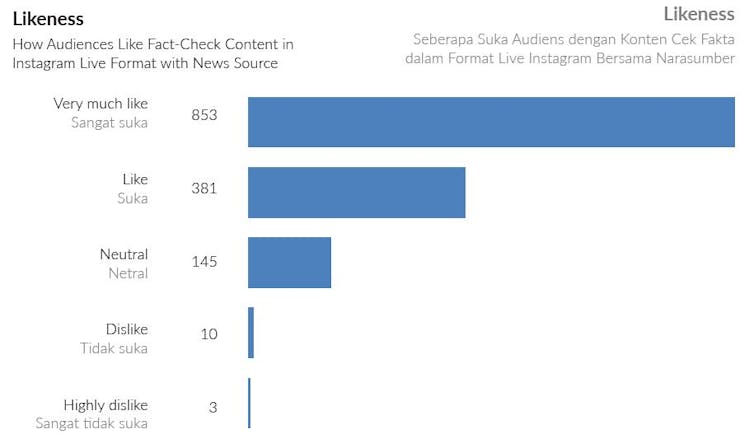

Up to 853 respondents (60.8%) stated very much liked fact checks in the form of live Instagram posts. Both fact-check formats, short videos with background music and live Instagram, are preferred over lengthy fact-check texts. The comparison of audience choices can be seen in the following graphs.

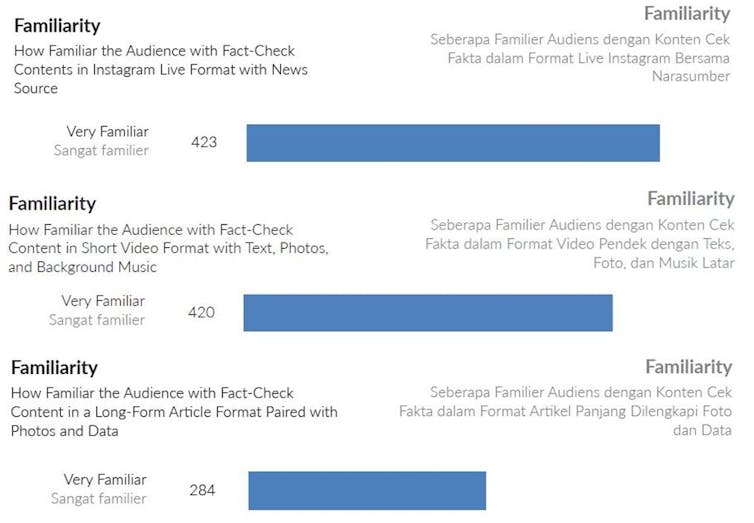

In the context of the fact-check format, our data shows that the majority of audiences in Indonesia consider themselves to be “very familiar” with short video with background music and Instagram live as their preferred formats for fact-check contents.

Conversely, they express lower level of familiarity to text content.

Evaluation for fact-check fighters

Indonesian journalists have been combating misinformation for years. AMSI and AJI have been working with Google News Initiative extensively, training more than thousands of journalists in 2018 and 2019.

The 2020 GNI report reveals that the Cek Fakta initiative has trained more than 10,800 journalists since 2018.

A team of more than 10,000 trained journalists is a huge cyber army. They have been fighting misinformation by producing fact-checks. Three years is enough time to start evaluating whether the content they produced are liked by the audience.

Our research only provides initial recommendations. The Indonesian press needs to produce more visual-based content so that the campaign against misinformation continues.

Our research recommends that fact-check content need to be visually engagng to attract public attention. Otherwise, the public can simply ignore them.

In the context of the 2024 general election, fact checking is getting more important to ensure that the public gets the right information, so that they can make relevant political decisions.

Without fact-checks, the public could to be trapped in a wave of propaganda campaigns and lies, as happened in the 2019 general election.

Fact-checking initiatives are important and can enhance public understanding. But if they fail to capture public attention, there is little point in the exercises.