Former federal NDP leader Ed Broadbent was one of the good ones.

News of his death at age 87, announced on Jan. 11, has inspired a wave of tributes, including from former political opponents. Brian Mulroney called Broadbent a “giant in the Canadian political scene” and rightly said he would have been prime minister had he led any other party.

I still smile thinking about a photograph taken during the 1988 election when Broadbent gamely had the Vachon brothers, beloved wrestlers from Québec who were NDP candidates, in a double headlock. It was silly, and great political theatre.

However, Broadbent’s political legacy was a mixed one.

Turning point in history

Riding high in the polls, the NDP decided to play it safe in the 1988 election and play down the divisive free trade issue. It was a monumental mistake — for the NDP, certainly, which saw the John Turner Liberals capture the issue, but also for the country.

Brian Mulroney’s Tories won in what was a de facto referendum on the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement and, as it turned out, a turning point in 20th century Canadian political history.

The free trade election rocked the federal NDP to its very foundations. Bob White, president of the Canadian Auto Workers, and a vice president of the federal party, was livid. He drafted an angry seven-page letter to the NDP executive a few days later, as he “watched the disintegration of what should have been the New Democratic Party’s finest hour.”

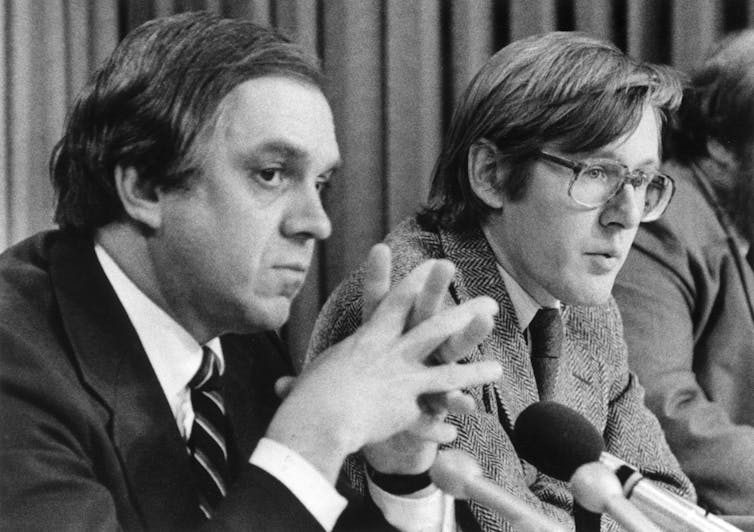

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Fred Chartrand

For White, the election strategy and result were nothing short of disastrous and warranted a full debate within the party. The executive of the Canadian Labour Congress met two days after the election. In his letter he said, “their level of anger, frustration and concern about the campaign, was the most emotional I have ever seen.”

Somehow, the NDP — the party of labour — did not grasp the central importance of free trade for working class Canadians.

White reminded the party leadership that, for the past three years, the labour movement had mobilized on this issue across the country:

“While a lot of our concern was expressed about jobs, even more dealt with social programs, environment, regional assistance, energy, privatization, deregulation, etc. In other words, not a narrow self-interest approach.”

With business organizations lining up on the other side of the debate, why didn’t the party of working people understand what was at stake?

In answering this question, White declared that: “we didn’t fail by accident — but rather, we failed by design.” Indeed, “if ever there is an issue the social democratic movement in Canada should oppose with total emotion and strength, it is this deal.”

The Free Trade Agreement’s legacy

Broadbent resigned as NDP leader soon after the election after 14 years of leading the party.

The timing of the Free Trade Agreement could not have been worse for Canada’s manufacturing sector, given the high Canadian dollar, which had risen from 70 cents to the U.S. dollar in 1986 to 89 cents in 1991.

There were other factors at play, such as higher interest rates and the imposition of the goods and services tax (GST) by the Mulroney government.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/UPC/Rod MacIver

In short order, Canada’s branch plant economy was made largely redundant as multinational corporations restructured their operations in favour of global supply chains, rather than branch plants serving national markets.

Employment in Ontario’s manufacturing industries as a percentage of the workforce, dropped like a stone from 30.2 per cent in 1981 to just 18 per cent in 1991.

In an interview with Bob Rae, NDP premier of Ontario from 1990 to 1995, in April 2023 for a book I’m writing about his government, he told me the “initial impact of free trade in Ontario in 1990 was terrible. It was a disaster. Because you had all of these companies that were closing down branch plants left and right.”

Lessons from the past

There is a lot of talk these days about “just transitions,” especially in the context of climate change. We can learn a lot from the profoundly unjust transition after free trade.

There were no special adjustment measures. Instead, the Mulroney government restricted eligibility for unemployment insurance, pushing many directly onto provincial welfare rolls. Even severance pay was clawed back.

The 1988 election was a watershed in Canadian politics, sweeping aside the economic nationalism that had been a bulwark against neoliberal globalization. Thereafter, protectionists were to the new global order what the Luddites had been to the industrial revolution: objects of ridicule and scorn.

The extreme income disparity and political polarization we see today, at least in part, is the direct result of the path we took in 1988. We will never know if Broadbent’s election would have made a difference, and this makes me sad with his passing.